Researchers Develop Artificial Cartilage That More Closely Mimics the Structure and Flexibility of Natural Joints

A research team from Washington State University, working alongside collaborators at Cornell University, has taken a significant step toward engineering artificial cartilage that behaves much more like the real thing. Their study outlines a method for growing cartilage with adjustable properties, allowing different regions of the tissue to develop distinct characteristics—just like natural cartilage found in human joints. This new approach not only aims to replicate cartilage’s complex three-layer structure but also introduces a way to make corrections during the growth process so the final tissue is closer to what the human body actually needs.

Cartilage damage is a major issue worldwide, especially as populations age. When the cartilage around knees, hips, and shoulders begins to wear down, it doesn’t naturally heal because it lacks its own blood supply. That means even small injuries can accumulate, eventually leading to chronic pain or joint failure. Today’s most common solutions rely on pain medication, limited mobility aids, or invasive joint replacements—a procedure with long recovery times and enormous costs. In the U.S. alone, joint replacements amount to roughly $140 billion each year. These limitations make engineered cartilage an extremely important area of research, and this new work attempts to address several of the major challenges that have stalled progress.

Why Artificial Cartilage Is Difficult to Engineer

Natural cartilage in weight-bearing joints is incredibly specialized. Though it is only about two to four millimeters thick, it is built like a three-layered system:

- A stiff bottom layer tightly attached to bone with vertical fibers that anchor the cartilage.

- A middle layer that acts as a shock absorber, dispersing force during movement.

- A smooth, flexible top layer that reduces friction and allows joints to glide comfortably.

Attempts to grow cartilage outside the body often fall short because they produce only soft, spongy tissue, similar to the cartilage found in ears or noses. While useful for non-load-bearing regions, this soft material cannot survive the intense compression and friction inside knee or hip joints. As a result, current engineered cartilage is limited to very small repairs and is not recommended for major joint restoration.

A New Bioreactor Designed for Layered Cartilage

The WSU team focused on designing a bioreactor capable of producing cartilage with variable characteristics, meaning different parts of the tissue can develop different mechanical strengths. To achieve this, the researchers used bone-marrow-derived stem cells, which have the ability to transform into various specialized cell types—including the cells that build cartilage.

Their bioreactor produces a gradual change in fluid shear, a physical force created by fluid movement. As fluid flows through a tapered chamber, the shear experienced by the cells changes depending on location. This gradient plays a crucial role in influencing how the cells behave. In areas where shear is higher, cells tend to produce stiffer material. Where shear is lower, the cells generate more flexible cartilage.

This means the bioreactor can grow a single piece of cartilage where one section is firm and structured, another is impact-absorbing, and another is smooth and pliable—a major step toward recreating natural tissue organization.

Real-Time Feedback to Prevent Unwanted Cell Changes

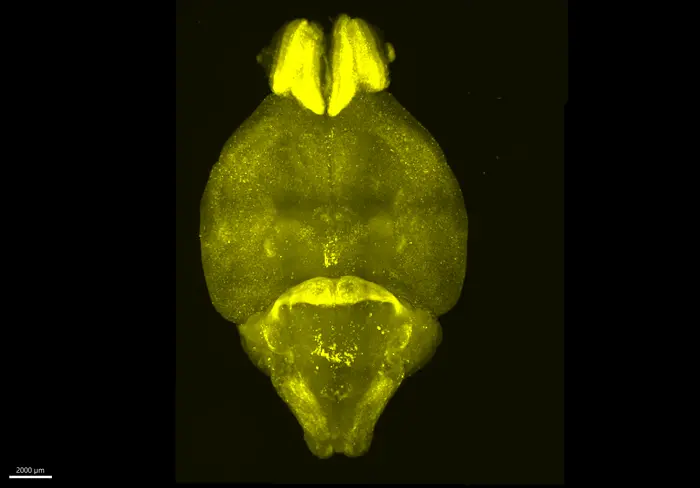

One of the largest problems in cartilage engineering is that stem cells sometimes drift into producing bone instead of cartilage. When bone begins to form, the resulting tissue becomes unusable, wasting weeks of growth time. The researchers developed a clever solution: a fluorescent protein monitoring system built directly into the cells.

- When cells begin producing bone-related materials, a red fluorescent signal appears.

- When they successfully produce cartilage, a green fluorescent signal appears.

This allows scientists to see exactly what the cells are doing while the tissue is still growing, rather than waiting until the end. If bone production is detected, they can intervene immediately to silence the unwanted genes and redirect the process. This is essentially real-time quality control, something that traditional cartilage engineering methods do not offer.

The team emphasized that the goal is not just to follow a recipe and hope for the best. Instead, they are developing a corrective, adaptable system that actively responds to the tissue as it forms, increasing the likelihood of success.

The Next Phase of Research

Going forward, the researchers plan to study how mechanical pressure—not just shear forces—affects stem cell behavior. Pressure is an important factor because cartilage in the body constantly experiences compression. Understanding how cells respond to pressure could help further refine the engineering of tissue that can withstand real-world joint movement.

While this project focuses on cartilage, the underlying principles can be used for many types of tissue that require variable mechanical properties. The team mentions potential applications for ligaments, cardiopulmonary tissues, renal tissues, liver tissues, and even neuronal structures. The ability to grow tissue with adjustable characteristics opens the door to a wide range of regenerative medicine possibilities.

What Makes Natural Cartilage So Unique?

To appreciate the significance of this breakthrough, it helps to understand what makes cartilage such a difficult material to replace.

- It is avascular, meaning no blood vessels supply it with nutrients.

- It relies on mechanical loading—normal movement—to circulate nutrients from joint fluid.

- It contains a specialized network of collagen and proteoglycans that give it both strength and flexibility.

- Its cells, called chondrocytes, exist in very low numbers and divide extremely slowly.

Because of this complexity, most synthetic replacements (such as plastics used in joint implants) cannot mimic the subtle performance of natural cartilage. Even engineered biological materials often fail to replicate the exact gradient of stiffness found in real tissue. That makes the WSU bioreactor’s ability to generate position-dependent cartilage properties particularly noteworthy.

Broader Context: How Cartilage Engineering Is Evolving

In recent years, researchers worldwide have explored various strategies to overcome cartilage’s regenerative limitations:

- 3D-printed scaffolds designed with pores or gradients to guide tissue growth.

- Hydrogels that imitate the water-rich environment of natural cartilage.

- Gene-editing techniques to boost cartilage-related protein production.

- Bioreactors that apply compression or tension during growth.

However, most systems struggle to produce tissue that truly matches the biomechanical performance of natural cartilage. The WSU approach stands out because it attempts to control both cell behavior and tissue structure simultaneously, and it does so with a built-in feedback loop to prevent mistakes.

Why This Work Matters for Real-World Patients

If this technology continues to advance, it could dramatically improve outcomes for patients with:

- Osteoarthritis

- Sports injuries

- Degenerative joint disorders

- Cartilage loss following trauma

Instead of replacing entire joints with artificial implants, doctors might one day implant living, custom-grown cartilage patches tailored to each patient’s needs. Such patches would restore natural movement without the long recovery time associated with full joint replacements.

Research Reference

Effects of a Gradated Fluid Shear Environment on Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Chondrogenic Fate – https://doi.org/10.1021/acsbiomaterials.5c01183