Rhode Island’s Eat Well, Be Well Program Shows Early Promise but Reveals Clear Gaps in Access, Awareness, and Impact

Rhode Island launched the Eat Well, Be Well program in January 2024, becoming the first state in the U.S. to offer a statewide financial incentive encouraging SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) households to buy more fresh fruits and vegetables. The idea was simple: make healthy food more affordable by rewarding people every time they choose produce. All SNAP recipients were automatically enrolled, removing extra paperwork or enrollment barriers that often limit participation.

The structure of the program is straightforward. For every $1 spent on fresh fruits or vegetables at participating retailers, households receive $0.50 in SNAP benefits, with a monthly limit of $25. These incentives are added directly onto recipients’ EBT cards, and the bonus money can then be used to purchase any SNAP-eligible item. At launch, the only participating retailers were Stop & Shop and Walmart locations across Rhode Island. Eligible items included fresh fruits, fresh vegetables, edible seeds, fresh herbs, salad kits (even those with added items like dressing or cheese), and potted fruit or herb plants. The intention was to keep definitions broad enough to be practical while retaining a focus on fresh produce.

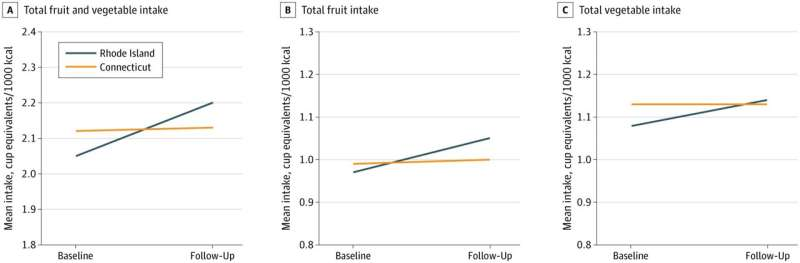

A team of researchers from the University of Rhode Island, Brown University, and the University of Illinois Chicago conducted an independent evaluation of the program’s effectiveness, with results published in JAMA Network Open. The study tracked the diets of 364 SNAP recipients in Rhode Island and compared them with 361 SNAP recipients in Connecticut, which does not have a similar incentive program. Participants were monitored before the program began and again five to eight months after it launched. This design allowed researchers to measure changes in fruit and vegetable intake while controlling for general trends not tied to the program itself.

The demographic makeup of the study participants was notable. Most were women—94% in Rhode Island and 96.4% in Connecticut. Participants had to be at least 18 years old, speak English or Spanish, and have access to both email and a text-capable phone. Community partners assisted the research team in reaching and recruiting households across both states.

The core findings showed a mixed picture. Households in Rhode Island who already had a higher baseline intake of fruits and vegetables increased their consumption more than those in Connecticut. In contrast, those with a lower baseline intake showed little or no change after several months of the program. This suggests that financial incentives may be more effective for people who were already leaning toward healthier eating habits. Researchers emphasized that the difference between Rhode Island and Connecticut is likely attributable to the program itself, since other conditions were similar across the two groups.

One of the most surprising findings was the low level of awareness about the program despite automatic enrollment. Only about one-third of participants could accurately describe what Eat Well, Be Well actually offered, and only about one in four reported using the discount. This indicates that the challenge is not just about designing incentives—it’s also about ensuring households know they exist and understand how to use them.

Researchers pointed to several possible reasons why households with low baseline fruit and vegetable intake did not see a measurable increase. Many of these households may face structural disadvantages, including limited transportation, which can reduce their ability to access participating stores. Others may have lower disposable income even within SNAP, meaning that even with incentives, produce may still feel unaffordable or impractical. Some households may lack adequate kitchen space or time for food preparation, making fresh produce a less attractive option.

Another factor is the economic environment in which the program operates. Rising food costs and slow updates to SNAP benefit amounts mean families are already struggling to stretch funds throughout the month. If participants need to shop at more expensive stores—such as large chain supermarkets—to access the incentive, the monthly grocery budget may become harder to manage. Fresh produce also tends to be more perishable than other staples, which influences how households plan meals and minimize waste.

Low program awareness also points to potential shortcomings in communication strategy. Automatic enrollment removes administrative barriers, but it does not guarantee understanding. Households may have received notices but not recognized their importance, or they may have been confused about where and how the incentives apply. Given that only two major retailers participated during the study period, many SNAP recipients who typically shop at discount outlets or small local markets may not have been exposed to in-store signage or promotional materials.

The study’s authors emphasize that while the Eat Well, Be Well model has strong potential, implementation details matter deeply. Simply offering incentives does not ensure broad adoption or meaningful diet changes across a diverse population. To improve outcomes, researchers recommend expanding retailer participation, increasing communication efforts, and exploring options to include other forms of produce such as frozen or canned fruits and vegetables. These additions could help reach households that struggle with transportation or that rely on longer-lasting, lower-cost options.

The research team is already conducting a follow-up study, examining data collected 17 to 20 months after the program launched. This longer-term analysis will shed light on whether initial patterns persist, improve, or diminish over time. They are also looking at how the incentives impact entire households—not just the enrolled adults—including effects on children’s diets. Qualitative interviews with participants and community stakeholders aim to uncover barriers that data alone cannot show, such as perceptions about produce prices, shopping habits, and the convenience of participating stores.

Understanding how and why SNAP recipients make food choices is essential for designing effective nutrition programs. Incentives like Eat Well, Be Well offer a promising tool, but only when combined with practical accessibility, strong communication, and a wider range of participating vendors. Broader economic pressures—from inflation to stagnant SNAP updates—shape how meaningful these incentives feel in daily life. Future program improvements will likely need to address these real-world constraints rather than relying on financial rewards alone.

Rhode Island’s effort marks a significant milestone in state-level nutrition policy. It demonstrates both the potential of produce incentive programs and the limitations of relying solely on financial nudges to change eating habits. As future data emerges, policymakers across the country will likely look to this program as a blueprint for designing or refining their own approaches to improving nutrition among SNAP households.

Research paper:

Evaluation of a State-Level Incentive Program to Improve Diet

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2841543