Risk of Death After Surgery Is Significantly Higher for People Living in Low-Income Neighborhoods, Major Study Finds

A large new Canadian study has found a troubling and persistent link between neighborhood income and survival after surgery, showing that people living in lower-income areas face a much higher risk of dying within a month of elective operations. The findings come from research conducted at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto and highlight how deeply social and economic conditions can shape health outcomes—even in countries with universal health care.

The study, published in JAMA Network Open, analyzed data from more than one million patients across Ontario who underwent planned inpatient surgery between 2017 and 2023. Researchers found that patients from the lowest-income neighborhoods had a 43 percent higher chance of dying within 30 days of surgery compared to those from the highest-income neighborhoods.

What makes these findings especially striking is that the disparity remained even after accounting for many factors that typically influence surgical outcomes, including age, pre-existing health conditions, type and complexity of surgery, and even the hospital where care was provided.

A Massive, Province-Wide Analysis

To reach these conclusions, the research team examined 1,036,759 adult patients who underwent elective inpatient surgical procedures across Ontario. The data came from ICES, an independent Canadian research institute that links and analyzes health care and demographic information for nearly the entire provincial population.

Patients were grouped based on the income level of the neighborhood they lived in, using standardized income quintiles derived from census data. This approach allowed researchers to look beyond individual income and focus on area-level socioeconomic conditions, which often reflect access to resources, housing quality, education, and community support.

The primary outcome measured was death within 30 days of surgery, a widely used benchmark for assessing surgical safety and quality of care.

The Numbers Tell a Clear Story

The raw numbers already showed a clear gap. About 0.9 percent of patients from the lowest-income neighborhoods died within 30 days of surgery, compared with 0.6 percent of patients from the wealthiest areas.

When researchers ran unadjusted analyses, patients in the lowest-income neighborhoods had 52 percent higher odds of dying within 30 days. After adjusting for clinical and hospital-related factors, the risk remained alarmingly high at 43 percent greater odds.

Even more telling was the income gradient observed in the results. The risk of death did not simply jump between the poorest and wealthiest groups. Instead, it increased steadily as neighborhood income decreased, suggesting a dose-response relationship between socioeconomic disadvantage and surgical mortality.

Universal Health Care Does Not Eliminate Inequality

Canada’s health care system is publicly funded, meaning patients do not pay out-of-pocket for hospital care or surgery. In theory, this should reduce disparities linked to income. However, the study shows that universal coverage alone is not enough to ensure equal outcomes.

Because patients across income groups were treated within the same publicly funded system—and often in the same hospitals—the findings strongly suggest that factors outside the operating room play a major role.

Hospital-level characteristics explained only a modest portion of the variation in outcomes. This means differences in hospital quality, staffing, or surgical expertise cannot fully account for why poorer patients fare worse.

Looking Beyond the Operating Room

The researchers point to upstream social determinants of health as likely contributors to the observed disparities. These include factors that affect patients before and after surgery, such as access to primary care, chronic disease management, nutrition, housing stability, transportation, and social support.

For example, patients from lower-income neighborhoods may experience longer wait times to see specialists, delayed diagnoses, or poorer control of chronic conditions like diabetes or heart disease prior to surgery. After discharge, they may face barriers to follow-up care, medication adherence, or rehabilitation services.

The study also examined whether immigration status played a role in postoperative mortality. After adjustment, recent immigration was not independently associated with higher 30-day death rates, reinforcing the idea that economic conditions, rather than immigration itself, are a key driver.

Why 30-Day Mortality Matters

Thirty-day mortality is considered a critical indicator of surgical quality because it captures not only what happens during the operation, but also the early recovery period. Complications such as infections, blood clots, or organ failure often emerge days or weeks after surgery, particularly if patients lack adequate support at home.

Higher mortality in this window suggests that recovery environments and post-discharge care are just as important as surgical skill.

Broader Evidence on Income and Health

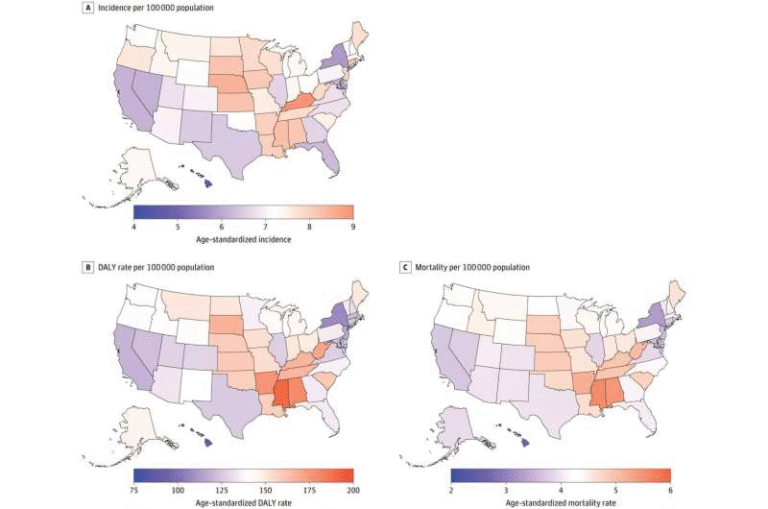

This study fits into a growing body of research showing that where people live can strongly influence their health outcomes. Neighborhood income is often linked to environmental exposures, stress levels, food security, and access to health-promoting resources.

Similar patterns have been observed in areas such as heart disease, cancer survival, and maternal health, where patients from disadvantaged communities consistently experience worse outcomes—even when medical care is technically available to all.

In surgery specifically, prior studies have linked socioeconomic disadvantage to higher complication rates, longer hospital stays, and increased likelihood of readmission.

What This Means for Health Policy

Rather than offering immediate solutions, the researchers describe their findings as a problem statement—a clear signal that current systems are not addressing the full range of factors influencing surgical outcomes.

Improving equity will likely require interventions that extend beyond hospitals, such as better preoperative optimization, stronger post-discharge support, and closer integration between surgical care and community-based health services.

The study underscores a simple but powerful message: health outcomes are shaped long before a patient enters the operating room.

Final Thoughts

The takeaway from this research is both sobering and instructive. Even in a system designed to provide equal access, income and neighborhood conditions still matter—sometimes in life-or-death ways. Addressing these gaps will require acknowledging that surgery does not happen in isolation, and that social and economic realities are inseparable from medical care.

As health systems aim to improve safety and outcomes, studies like this remind us that true equity means looking beyond procedures and protocols to the real-world conditions patients live with every day.

Research paper:

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2843731