Scientists Build the First Fully Synthetic Brain-Like Tissue Model for More Precise and Humane Neurological Research

Scientists have created the first functional, fully synthetic brain-like tissue model that does not rely on any animal-derived materials or biological coatings. This breakthrough could transform how neurological diseases are studied and how drugs are tested, offering a cleaner, more controlled, and more ethical alternative to existing brain-model systems.

The goal of neural tissue engineering has always been to recreate something that closely resembles the structure and function of the human brain, but past systems often depended on biological coatings such as laminin or fibrin, or they relied on animal tissue altogether. These materials introduce variability because their exact molecular composition is difficult to reproduce consistently. The new model solves that problem by using a defined, synthetic scaffold made from polyethylene glycol (PEG)—a well-known, chemically neutral polymer.

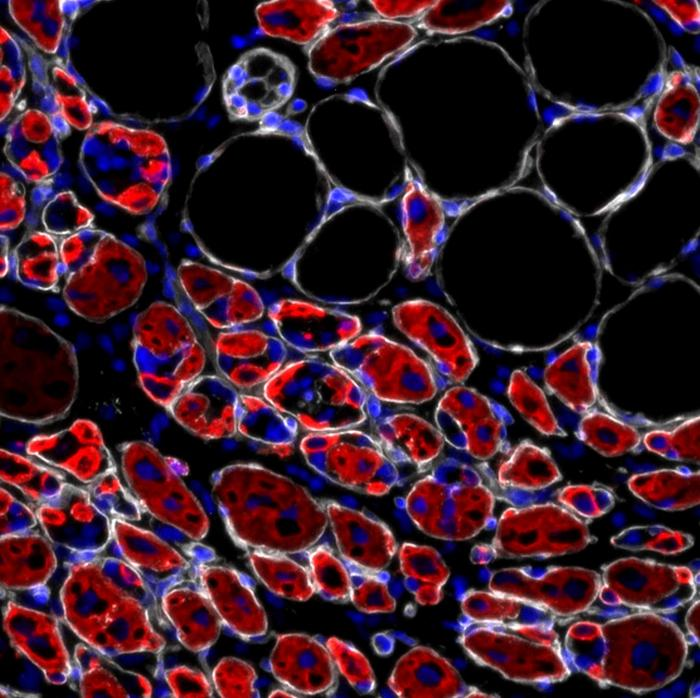

PEG normally does not allow living cells to attach to it. In most tissue-engineering approaches, scientists must modify PEG by adding animal proteins. But in this study, researchers reshaped PEG into a maze-like network of interconnected, textured pores that brain cells can naturally recognize and colonize. This allows the cells not only to attach but also to mature and form functional neural networks with real signaling activity, opening the door to more accurate long-term studies of neurological conditions.

The research team, led by bioengineering experts at the University of California, Riverside, began working on the project in 2020. Their method involves channeling a mixture of water, ethanol, and PEG through a nested set of glass capillaries. As this mixture reaches an outer water stream, its components begin to separate. A flash of light is then used to stabilize this separation instantly, effectively locking in the porous structure. The result is a synthetic scaffold full of interconnected microchannels that permit oxygen and nutrients to flow freely—an essential requirement for keeping donor stem cells alive and encouraging them to organize into brain-like clusters.

This porous network is unusually efficient in supporting long-term cell growth because it imitates certain microscopic features of the natural extracellular matrix that surrounds neurons in the human brain. The material’s stability means researchers can study how cells behave over extended periods. This is especially important because mature brain cells behave differently from younger ones, and many diseases—including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and traumatic brain injuries—require models that reflect mature neural activity.

As the donor stem cells settle into this synthetic framework, they can begin to display donor-specific neural activity, which means drug developers can observe how a particular patient’s brain cells respond to specific treatments. This has major implications for personalized medicine, targeted drug testing, and potentially reducing the need for live animal experimentation.

Today, nearly all neurological drug research still depends heavily on rodent models. But rodents differ from humans in crucial genetic and physiological ways, resulting in many failed clinical trials despite successful animal testing. A platform like this could reduce or even eliminate the use of animal brains in certain types of research, aligning with ongoing FDA efforts to phase out animal-testing requirements in drug development.

Right now, the scaffold is quite small—only about two millimeters wide—but scaling it up is one of the team’s next major goals. They are also applying similar techniques to create synthetic models of other tissues, including the liver, and envision eventually developing a suite of interconnected organ-level cultures. Such a system could simulate how multiple organs interact in real time, offering a powerful tool for studying complex diseases and whole-body responses to medications.

An interconnected model would allow scientists to examine how a problem originating in one organ might affect another, or how a drug metabolized in the liver might influence brain activity. Building this kind of multi-organ platform has long been a vision in biomedical research, and fully synthetic scaffolds like this one make it a more realistic possibility.

Below is a deeper look into relevant scientific context and what this innovation means for the future of biomedical engineering.

What Makes a Synthetic Brain Model Different from Other Brain-Like Systems?

Many laboratories use brain organoids, which are tiny, self-organized clusters of cells grown from stem cells. While valuable, organoids tend to vary significantly from batch to batch, making reproducible research difficult. They also often lack proper nutrient distribution, leading to uneven growth.

Other systems rely on hydrogels or biological matrices derived from animals. These provide a supportive environment for the cells but are chemically inconsistent, and some raise ethical concerns.

The new PEG-based scaffold stands out because it is:

- Fully synthetic, meaning every component is precisely defined.

- Chemically stable, allowing long-term studies.

- Mechanically structured, with pores designed to mimic natural cell environments.

- Free of biological additives, offering strong reproducibility.

This level of control makes it possible to run drug tests that can be repeated across laboratories without the uncertainty introduced by biological variability.

Why PEG Is So Important in Tissue Engineering

PEG is widely used in medical and pharmaceutical technologies because it is:

- Non-toxic

- Water-soluble

- Chemically neutral

- Highly customizable

The challenge has always been that cells do not naturally attach to PEG. Overcoming this limitation without relying on proteins or animal materials is a major scientific milestone. By transforming PEG into a textured, porous matrix, the researchers effectively changed how cells interact with it, enabling adhesion, migration, and network formation.

This demonstrates that scaffold shape and architecture can be just as important—if not more so—than chemical composition when guiding cell behavior.

Broader Implications for Future Research

The ability to grow donor-specific, mature neural networks in a synthetic environment brings several benefits:

- More reliable drug screening

Drugs can be tested on models that closely mimic human brain physiology rather than animal models. - Cleaner data for disease modeling

Because the materials are defined and reproducible, scientists can more clearly isolate variables in experiments. - Personalized medicine

Patient-derived stem cells can reveal how an individual’s brain cells respond to treatments before administering them. - Reduced reliance on animal testing

Ethical and scientific motivations are pushing research toward animal-free alternatives. This scaffold directly supports that transition. - Potential for multi-organ integration

The long-term ambition is to link synthetic tissues—brain, liver, and others—to observe system-wide biological interactions, a step toward simulating human organ systems in the lab.

Looking Ahead

Although the current model is tiny and still in early development, the concept represents a major step for neuroscience and biotechnology. Creating functional neural tissue from fully synthetic materials demonstrates a powerful new direction for research: building customizable, stable, and ethically sound platforms that behave more like human organs.

As engineers refine the scaffold and successfully scale it, we may eventually see systems that offer unprecedented insight into brain function, disease progression, and therapeutic response.

The future of neurological research may rely less on traditional animal models and more on carefully engineered synthetic environments that bring us closer to understanding the human brain on its own terms.

Research Paper:

https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202509452