Scientists Develop a Highly Targeted Therapy That Could Transform Treatment for T-Cell Lymphomas and Leukemias

Scientists at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center’s Ludwig Center have developed a new precision therapy that could significantly change how T-cell lymphomas and leukemias are treated. The newly reported treatment selectively targets TRBC2-positive T-cell cancers, addressing a major gap that has long existed in therapies for these rare and difficult-to-treat malignancies.

This research builds on earlier work from the same team and expands a precision-based approach that now covers the majority of patients with T-cell cancers. The study was published in Nature Cancer and represents a major step forward in designing treatments that eliminate cancer cells while preserving enough of the immune system for patients to remain healthy.

Why T-Cell Cancers Are So Hard to Treat

T-cell lymphomas and leukemias affect roughly 100,000 people worldwide every year, yet they remain among the most challenging blood cancers to treat. Unlike B-cell cancers, which have benefited from decades of drug development and investment, T-cell malignancies are rarer, more biologically complex, and significantly underfunded in research.

One of the biggest problems lies in the role T cells play in the immune system. B-cell therapies can safely eliminate both healthy and cancerous B cells because patients can survive with limited B-cell function. T cells, however, are essential for fighting infections. Destroying too many healthy T cells can leave patients dangerously immunocompromised, making treatment far riskier.

As a result, outcomes for patients with relapsed T-cell cancers are often poor. Five-year survival rates range from just 7% to 38%, highlighting the urgent need for safer and more effective therapies.

The Key Insight: Targeting TRBC Variants

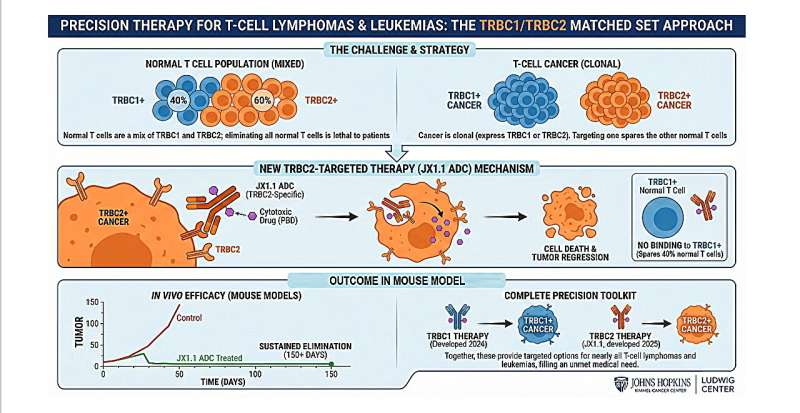

The new therapy focuses on a clever biological distinction within T cells themselves. Each T cell carries a receptor known as the T-cell receptor beta constant (TRBC), which exists in two mutually exclusive variants: TRBC1 and TRBC2.

In healthy individuals, normal T cells are a mix of both types, with approximately 40% expressing TRBC1 and 60% expressing TRBC2. However, when a T-cell cancer develops, all malignant cells express only one of these two variants, never both.

This creates a rare opportunity for precision targeting. By designing therapies that attack only the cancer-associated TRBC variant, doctors can eliminate malignant T cells while preserving a large fraction of healthy ones. This approach maintains enough immune function to protect patients from infections.

In 2024, the Johns Hopkins team introduced the first therapeutic antibody targeting TRBC1-positive cancers. Until now, there was no equivalent option for patients whose cancers express TRBC2, leaving nearly half of T-cell cancer patients without access to this precision strategy.

Developing a TRBC2-Specific Antibody

To solve this problem, researchers used a phage-displayed antibody library, a technology that allows scientists to rapidly screen millions of antibody candidates. Using this approach, they identified a new antibody, called JX1.1, that binds specifically to the TRBC2 protein and does not react with TRBC1.

The discovery process relied on SLISY, a next-generation sequencing-based platform designed to speed up antibody identification. This ensured that JX1.1 could precisely distinguish between the two highly similar TRBC variants, a challenge that had prevented TRBC2-specific therapies from being developed in the past.

Turning the Antibody Into a Cancer-Killing Weapon

Once the antibody was identified, researchers converted it into an antibody-drug conjugate (ADC). ADCs are a class of targeted cancer therapies that combine the precision of antibodies with the potency of chemotherapy.

In this case, JX1.1 was linked to pyrrolobenzodiazepine, a powerful cancer-cell-killing drug. The antibody guides the drug directly to TRBC2-positive cancer cells, where it is internalized and releases its toxic payload. This approach minimizes damage to healthy cells and maximizes effectiveness against tumors.

Impressive Results in Preclinical Testing

Laboratory tests and animal studies showed that the new ADC was highly selective for TRBC2-positive cancer cells. It clearly distinguished between TRBC2-positive tumors and TRBC1-positive normal T cells, confirming its precision.

In animal models of T-cell cancer, treatment with the JX1.1 ADC led to robust tumor regression with minimal toxicity. Most notably, all treated mice showed complete elimination of detectable cancer for the entire 150-day follow-up period, an unusually durable response in preclinical cancer research.

These results suggest that the therapy effectively kills cancer cells while sparing enough normal T cells to avoid severe immune suppression.

A Matched Precision Toolkit for T-Cell Cancers

With both TRBC1- and TRBC2-targeting antibodies now available, researchers have created what they describe as a matched precision toolkit. Together, these therapies could be applied to the vast majority of patients with T-cell lymphomas and leukemias, regardless of which TRBC variant their cancer expresses.

This dual-target approach is especially important because it avoids the “one-size-fits-all” strategy that has historically failed in T-cell cancers. Instead, treatment can be tailored based on a patient’s specific tumor biology.

How Antibody-Drug Conjugates Are Changing Cancer Care

Antibody-drug conjugates have become one of the most promising areas in modern oncology. By delivering chemotherapy drugs directly to cancer cells, ADCs aim to increase effectiveness while reducing side effects.

Several ADCs are already approved for cancers such as breast cancer and certain leukemias. The success of the TRBC2-targeted ADC adds to growing evidence that precision-guided drug delivery can outperform traditional chemotherapy, especially in cancers where preserving healthy tissue is critical.

For T-cell malignancies, this approach is particularly valuable because it avoids the catastrophic immune damage that broader T-cell-depleting therapies can cause.

What This Could Mean for Patients

While the therapy is still in the preclinical stage, the results are encouraging. The study provides strong justification for advancing TRBC2-targeted ADCs toward clinical trials, where safety and effectiveness in humans can be evaluated.

If future trials confirm these findings, patients with TRBC2-positive T-cell cancers could gain access to a treatment option that is both highly effective and significantly safer than existing therapies.

Research Reference

TRBC2-targeting antibody–drug conjugates for the treatment of T-cell cancers, Nature Cancer (2025)

https://www.nature.com/articles/s43018-025-01069-z