Scientists Discover a Non-Hallucinogenic Psilocybin Brain Receptor That Could Transform Depression and Anxiety Treatment

Psilocybin, the naturally occurring psychedelic compound found in certain “magic” mushrooms, has attracted serious scientific attention over the past decade. Clinical trials have repeatedly shown that it can produce long-lasting relief from depression and anxiety, sometimes after just a single dose. However, psilocybin’s hallucinogenic effects have remained a major obstacle, making treatment expensive, highly regulated, and potentially risky for some patients.

Now, a new study from Dartmouth College points to a promising breakthrough. Researchers have identified a specific brain receptor that delivers psilocybin’s therapeutic benefits without causing hallucinations. This discovery could pave the way for safer, more accessible treatments for mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety.

A Shift in How Scientists Understand Psilocybin

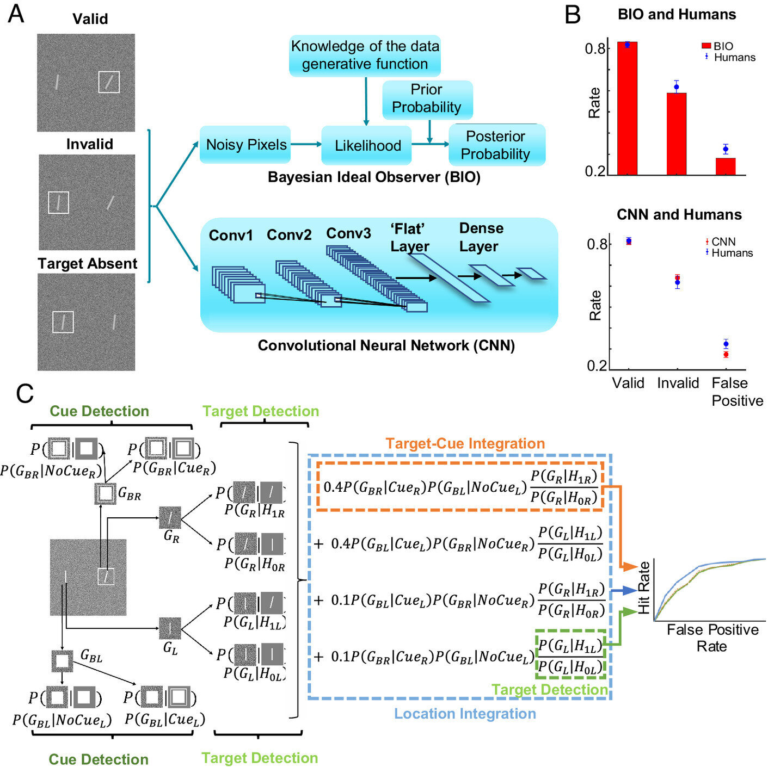

Traditionally, the effects of psilocybin have been closely associated with one serotonin receptor in the brain: 5-HT2A. Activation of this receptor is known to cause the vivid perceptual changes and altered states of consciousness commonly associated with psychedelic experiences.

Because of this, most research has focused on the idea that hallucinations and therapeutic benefits are tightly linked. Some studies have even attempted to block the 5-HT2A receptor in order to reduce hallucinations, but the results have been inconsistent. In many cases, reducing hallucinogenic effects also weakened the antidepressant and anti-anxiety benefits.

The new Dartmouth study challenges that assumption.

Instead of focusing solely on the hallucinogenic pathway, the researchers asked a different question: Could psilocybin’s mental health benefits be coming from other serotonin receptors entirely?

The Discovery of the 5-HT1B Receptor’s Role

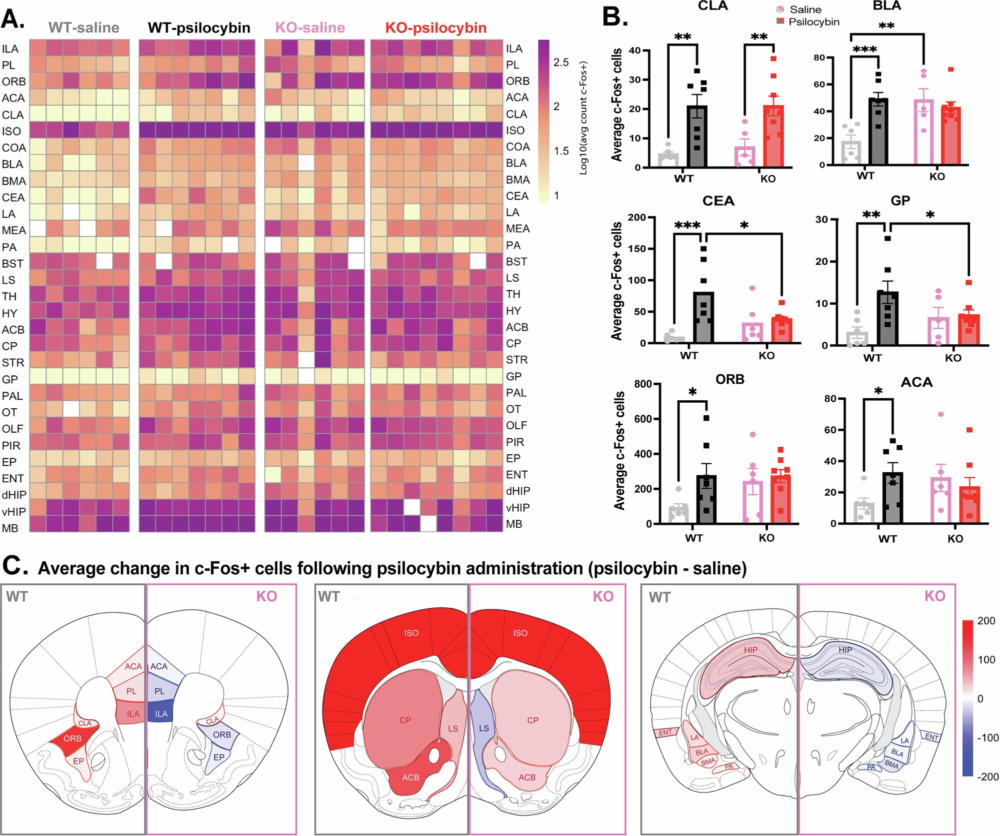

The study, published in the journal Molecular Psychiatry, identifies the serotonin 1B receptor (5-HT1B) as a key contributor to psilocybin’s antidepressant and anti-anxiety effects. Importantly, this receptor does not produce hallucinations when activated.

Using a newly developed animal model, the researchers studied how psilocybin affected both brain activity and behavior in mice. They found that while hallucinogenic-like behaviors were still linked to the 5-HT2A receptor, the positive behavioral effects related to mood and anxiety depended strongly on the 5-HT1B receptor.

When the function of the 5-HT1B receptor was disrupted, many of psilocybin’s beneficial effects were significantly reduced, even though hallucinogenic signaling remained intact. This separation between therapeutic and hallucinogenic pathways is what makes the finding so important.

Why This Matters for Mental Health Treatment

Depression and anxiety disorders affect hundreds of millions of people worldwide, and many patients do not respond well to existing treatments such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Psilocybin has stood out because it can produce rapid and long-lasting improvements, sometimes lasting weeks or even months after a single dose.

However, its hallucinogenic nature creates several challenges:

- Patients must be monitored by trained professionals during treatment

- Sessions are time-intensive and expensive

- Individuals with certain psychiatric conditions, such as schizophrenia or a family history of psychosis, are often excluded due to safety concerns

By identifying a non-hallucinogenic receptor responsible for therapeutic benefits, researchers may be able to design psilocybin-like medications that avoid these issues altogether.

Such treatments could potentially be administered more like conventional antidepressants, without the need for supervised psychedelic sessions.

Understanding Psilocybin and the Serotonin System

Psilocybin works by interacting with the brain’s serotonin system, which plays a central role in regulating mood, appetite, sleep, and emotional processing. Once ingested, psilocybin is converted into psilocin, the active compound that binds to serotonin receptors.

What makes psilocybin particularly complex is that it does not bind to just one receptor. Instead, it interacts with multiple serotonin receptor subtypes, including 5-HT2A, 5-HT1A, 5-HT2C, and now, importantly, 5-HT1B.

The serotonin system is highly conserved across species, meaning that findings in mice are often relevant to humans. Interestingly, the 5-HT1B receptor is already a known target for several anti-migraine medications, suggesting it may be a safer and more familiar pathway for drug development.

Reducing Risks While Preserving Benefits

One of the biggest concerns with psychedelic therapy is the risk of triggering psychosis, particularly in individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders or a genetic vulnerability to psychotic conditions. Even in healthy individuals, psychedelic experiences can sometimes lead to intense anxiety or distress, commonly referred to as “bad trips.”

Although clinical trials have shown that psilocybin can be administered safely under controlled conditions, doing so requires extensive safeguards, including trained guides, therapeutic preparation, and post-session integration.

If scientists can develop drugs that target the 5-HT1B receptor without activating hallucinogenic pathways, many of these risks could be reduced or eliminated. This could dramatically expand the number of people who are able to benefit from psilocybin-inspired treatments.

Legal and Regulatory Context

In the United States, psilocybin remains classified as a Schedule I controlled substance, making it illegal at the federal level. Despite this, regulatory attitudes are slowly changing.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has granted Breakthrough Therapy designation to psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression and major depressive disorder. This designation is intended to accelerate the development of promising therapies for serious conditions.

Additionally, some U.S. states have decriminalized psilocybin or introduced laws to regulate its supervised therapeutic use. Still, widespread medical adoption remains limited by cost, legal complexity, and safety concerns.

A non-hallucinogenic alternative could significantly ease these barriers.

What This Means for the Future of Psychedelic Medicine

This study adds to a growing body of research suggesting that hallucinations may not be necessary for therapeutic change. The idea that mental health benefits require a psychedelic “trip” is increasingly being questioned.

Pharmaceutical companies are already exploring non-hallucinogenic psychedelic-inspired compounds, sometimes referred to as psychoplastogens. These drugs aim to promote neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to reorganize and form new connections, without altering perception.

By highlighting the role of the 5-HT1B receptor, the Dartmouth study provides a clear biological target for this next generation of treatments.

A Promising Step, Not a Final Answer

While the findings are exciting, the researchers emphasize that this is not the final word on how psilocybin works. The brain is extraordinarily complex, and psilocybin’s effects likely involve multiple receptors and neural circuits working together.

Still, identifying a specific, non-hallucinogenic receptor linked to antidepressant and anti-anxiety effects represents a major step forward. It offers a new way to think about psychedelic medicine: not as an all-or-nothing experience, but as a set of mechanisms that can be selectively harnessed.

If future studies confirm these findings in humans, they could lead to safer, more affordable, and more widely available treatments for some of the most challenging mental health conditions.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41380-025-03387-1