Scientists Grow Mini Brains to Reveal the Cells Behind Autism-Related Brain Overgrowth

Scientists are getting closer to understanding one of the earliest biological clues linked to autism: unusually rapid brain growth during infancy. In a new study led by researchers at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, scientists successfully grew miniature human brains in the lab, known as brain organoids, to pinpoint the specific cell types and genes that influence early brain size. Their findings offer fresh insight into how autism-related brain changes may begin long before behavioral signs appear.

The research was conducted in the lab of Jason Stein, Ph.D., a genetics expert at UNC, and was led by Rose Glass, Ph.D., and Nana Matoba, Ph.D. The study was published in the journal Cell Stem Cell and represents one of the most detailed efforts so far to model early human brain development using stem cell technology.

Why Brain Size Matters in Autism Research

Over the past several years, scientists have identified early brain overgrowth as a potential biological marker for autism, particularly during the first year of life. Some infants who later receive an autism diagnosis show faster-than-average brain growth, especially in regions involved in cognition and social behavior.

Autism is known to be influenced by a combination of genetic factors and environmental exposures, and brain size has emerged as one measurable trait that reflects these underlying influences. However, until now, researchers have struggled to understand why certain brains grow faster than others and which cells are responsible.

This new study tackles that problem directly by recreating early brain development outside the human body, allowing scientists to observe growth processes in unprecedented detail.

Building Human Brain Development in a Dish

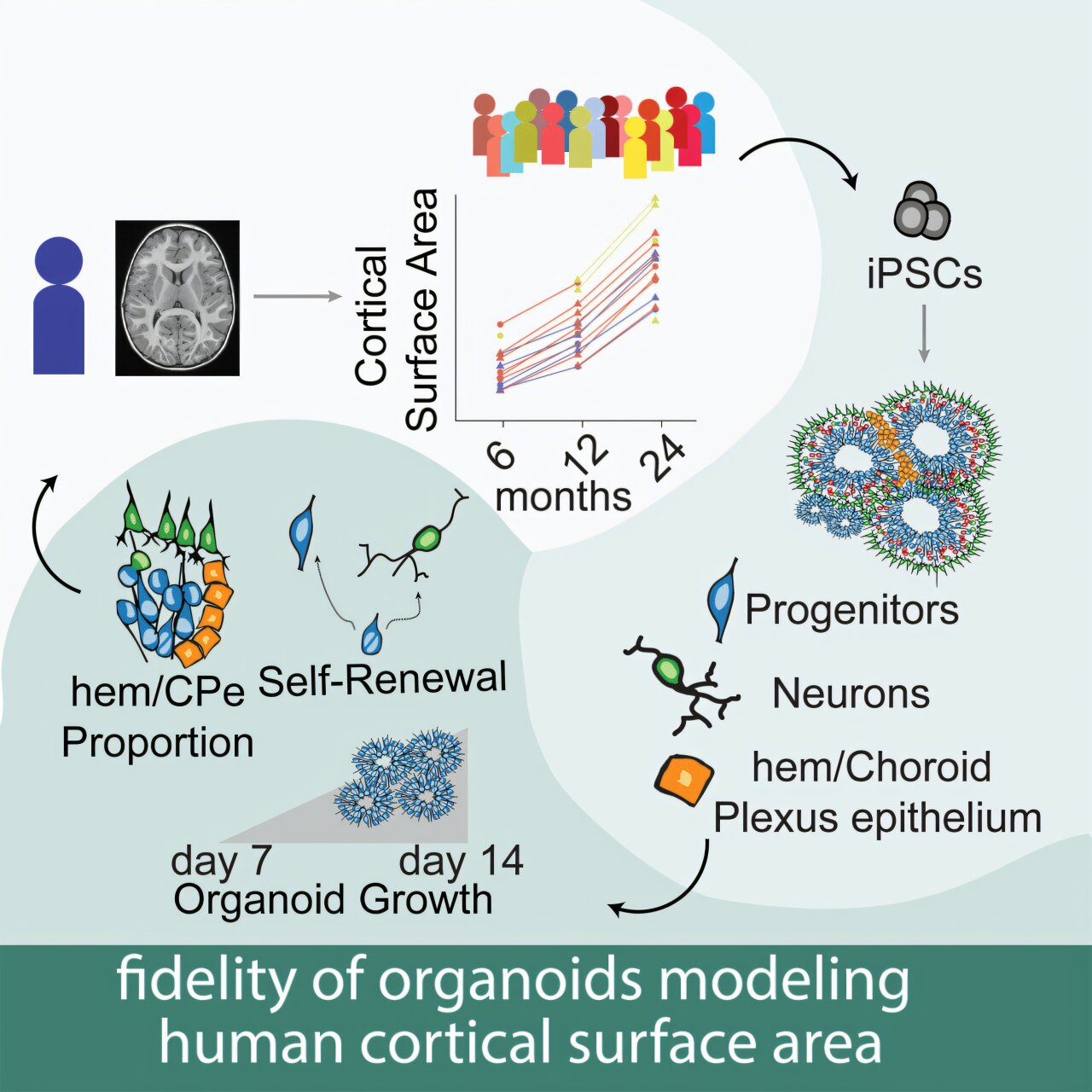

To carry out the study, researchers relied on data and samples from the Infant Brain Imaging Study (IBIS), a large, long-running research network focused on understanding autism risk in infancy. IBIS has followed infants with a high familial likelihood of autism for more than two decades, using MRI scans to track brain growth over time.

From this group, the research team collected whole blood samples from 18 individuals whose infant brain growth patterns were already well documented through imaging. From these samples, scientists isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells, a type of white blood cell, and reprogrammed them into pluripotent stem cells.

Pluripotent stem cells are remarkable because they can become almost any cell type in the human body. In this case, researchers guided them to develop into brain organoids, three-dimensional clusters of cells that mimic early human brain tissue in both structure and function.

These organoids do not think or feel, but they replicate many of the biological processes that occur during early brain formation, making them a powerful research tool.

Two Key Brain Cell Types Stand Out

When researchers examined the organoids more closely, they discovered that changes in two specific brain cell types were strongly linked to brain size differences seen in infancy.

The first cell type is neural progenitor cells. These are early-stage cells that generate neurons and other brain cells during development. The study found that higher gene expression activity in neural progenitor cells was associated with larger brain size. This relationship closely mirrored what had been observed in real infant brain scans, confirming that the organoids were accurately modeling human development.

The second cell type is choroid plexus epithelial cells. These cells form part of a specialized brain structure that produces cerebrospinal fluid and supports neural growth. The researchers found that variations in these cells were also linked to differences in brain growth, suggesting they play a previously underappreciated role in shaping early brain size.

Together, these findings provide strong evidence that early cellular behavior, rather than later developmental changes, can influence brain overgrowth linked to autism.

Confirming Organoids as a Reliable Research Model

One of the most important outcomes of the study was the validation of participant-derived brain organoids as a reliable model system. Organoids created from the same individual consistently showed similar growth patterns and gene expression profiles, reinforcing the idea that genetic background strongly shapes early brain development.

This confirmation opens the door for many future studies. Scientists can now use these models to explore how specific genes, environmental exposures, or medications affect early brain growth in ways that would be impossible to study directly in human infants.

Exploring Environmental Risk Factors

With the organoid model validated, the Stein lab is already expanding its research. One major focus is the impact of prenatal exposure to environmental toxicants, substances that may interfere with brain development during pregnancy.

A key compound under investigation is valproic acid (VPA), a medication sometimes used to treat epilepsy and bipolar disorder. Prenatal exposure to VPA has been linked to an increased risk of autism, but the biological mechanisms behind this association remain unclear.

Using brain organoids derived from individuals with and without autism, researchers are examining how both short-term and long-term exposure to such chemicals alters early brain development. This approach allows them to study how genetic risk factors may amplify environmental effects, providing a clearer picture of how autism-related traits emerge.

How Brain Organoids Are Changing Neuroscience

Brain organoids have become one of the most exciting tools in modern neuroscience. Unlike animal models, they are made from human cells, allowing researchers to study human-specific developmental processes. They also retain the unique genetic makeup of the individual, which is critical for understanding conditions like autism that vary widely from person to person.

However, organoids are not perfect replicas of real brains. They lack blood vessels, sensory input, and full cellular diversity. Despite these limitations, studies like this one demonstrate that organoids can still faithfully reproduce early developmental trends, including differences in brain growth trajectories.

As techniques improve, scientists expect organoids to play an even larger role in drug testing, genetic research, and personalized medicine.

Why This Study Matters

This research represents a major step forward in understanding autism at its earliest biological stages. By identifying specific cells and genes linked to infant brain overgrowth, scientists are moving closer to uncovering the mechanisms that contribute to autism risk.

Just as importantly, the study shows that it is possible to connect real-world brain imaging data with lab-grown human brain tissue, bridging a long-standing gap between clinical observation and molecular biology.

While this work will not lead to immediate diagnostic tools or treatments, it lays crucial groundwork for future discoveries. Understanding how and why some brains grow differently from the very beginning may eventually help researchers develop earlier interventions and more targeted therapies.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2025.12.001