Scientists Have Successfully Rewired a Fruit Fly’s Brain and Changed Its Behavior

Understanding how the brain wires itself during development has been one of neuroscience’s longest-running challenges. A new set of studies has now brought researchers closer than ever to cracking that puzzle. Scientists have not only uncovered key rules that guide how neurons choose their synaptic partners, but they have also demonstrated something even more striking: they can deliberately rewire a brain circuit and change behavior as a result. The work was carried out in fruit flies, a model organism that has been central to brain research for decades, and the findings were published in Nature in two closely related papers.

At the center of this research is the olfactory system of the fruit fly, which processes smells and directly influences behavior such as attraction, avoidance, and mating. Even though the fruit fly brain is tiny, it contains thousands of neurons organized into highly specific circuits. If these circuits are wired incorrectly, the animal’s behavior can change in dramatic and often maladaptive ways.

Why Brain Wiring Matters

The brain works because neurons form highly specific connections with one another. Each neuron sends out a long extension called an axon, which must find the correct dendrites of another neuron to form a functional synapse. In sensory systems like smell, this precision is especially important. If the wrong neurons connect, the brain may misinterpret signals from the environment.

In the fruit fly’s olfactory circuit, there are around 50 types of olfactory receptor neurons that detect odors from the antennae and roughly 50 corresponding projection neurons that relay this information deeper into the brain. Each receptor neuron type is normally paired with a specific projection neuron type. This precise matching ensures that certain smells trigger attraction while others trigger avoidance.

For decades, scientists have known that incorrect wiring could theoretically make an animal respond to the wrong cues, such as approaching harmful substances or failing to recognize appropriate mates. What remained unclear was how neurons reliably find their correct partners during development.

The Longstanding Theory of Molecular Tags

More than sixty years ago, neuroscientist Roger Sperry proposed that neurons might use chemical identifiers on their surfaces to recognize one another. According to this idea, neurons would carry molecular “tags” that help them find matching partners, much like a lock-and-key system.

Over time, researchers discovered many such cell-surface molecules, confirming that Sperry’s idea was broadly correct. However, there was a major problem: the number of known molecular tags seemed far too small to uniquely identify the enormous number of possible neuron pairings in a brain, even in insects.

Earlier work from the same research group showed that neurons simplify the problem by growing their axons along predefined paths rather than exploring the entire brain at random. This limits the pool of potential partners. Even so, neurons still encounter multiple possible matches, raising the question of how the final decision is made.

Attraction Alone Is Not Enough

In the first of the two new Nature papers, researchers focused on a subtle but critical idea: repulsion may be just as important as attraction in determining synaptic partner matching.

Traditionally, most attention had been given to attractive molecular cues that pull axons toward their correct targets. But neurons also express molecules that actively repel certain connections. Repulsion was already known to play a role in preventing neurons from connecting to themselves or from wiring incorrectly at early developmental stages.

To test whether repulsion also operates during the final stages of partner selection, the scientists studied two types of olfactory neurons that share the same attractive tags. From an attraction-only perspective, these neurons should be indistinguishable to incoming axons.

Using a single-cell RNA sequencing database, the researchers identified three previously unknown genes that produce cell-surface molecules acting as repulsive signals. When these genes were disabled, the wiring became confused: axons that normally connected to only one neuron type began connecting to both. This demonstrated that repulsive molecular tags are essential for ensuring correct synaptic specificity.

Rewiring the Brain on Purpose

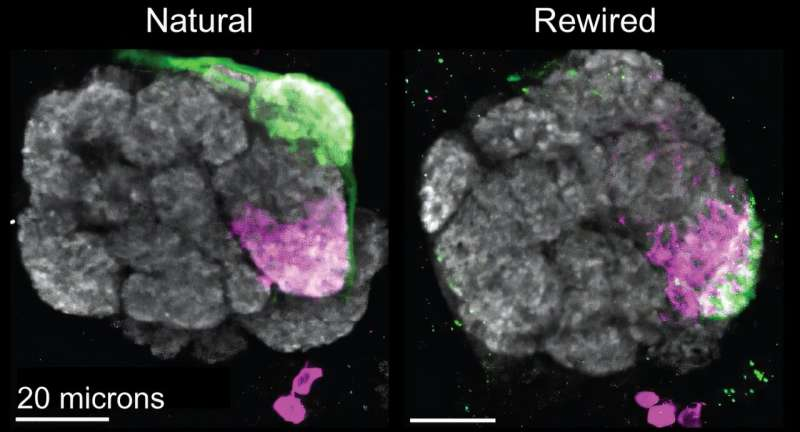

Discovering the role of attraction and repulsion was only part of the story. In the second Nature paper, the researchers took a bold step further. They asked whether a deep understanding of these molecular rules would allow them to intentionally reprogram neural wiring.

They focused on a specific olfactory receptor neuron known to influence mating behavior. Normally, this neuron helps suppress male fruit flies from courting other males. By carefully altering gene expression, the researchers changed the balance of molecular cues in three ways: they increased repulsion between the neuron and its usual partner, decreased repulsion toward a new partner, and increased attraction to that new partner.

The result was clear and measurable. The neuron’s axon was redirected to connect with a different projection neuron than it normally would. This confirmed that the researchers could predictably and reproducibly rewire a neural circuit by adjusting molecular signals.

Behavior Changes Along With Wiring

Perhaps the most compelling part of the study was what happened next. The rewired brain circuits did not just look different under the microscope; they produced different behavior.

Male fruit flies with rewired olfactory circuits began displaying courtship behaviors toward both males and females. These behaviors included chasing other males, extending wings, and producing courtship songs. In other words, altering a single circuit was enough to disrupt a deeply ingrained behavioral pattern.

This direct link between molecular wiring rules, circuit structure, and behavior provides some of the strongest evidence yet that scientists understand this system at a mechanistic level.

Why Fruit Flies Are So Important to Neuroscience

Fruit flies may seem far removed from humans, but they are one of the most powerful tools in brain research. Their brains are small enough to study in detail yet complex enough to display rich behaviors. Researchers also have access to advanced genetic tools that allow precise control over individual neurons.

In recent years, scientists have even completed a full wiring map of the adult fruit fly brain, cataloging around 139,000 neurons and tens of millions of synapses. This comprehensive background made it possible to interpret the new rewiring experiments in exceptional detail.

Broader Implications for Brain Science

Although this work focuses on the fly olfactory system, the principles uncovered are likely to extend far beyond it. Many animals, including mammals, rely on similar combinations of attractive and repulsive cues to guide neural development.

Understanding these rules could eventually help scientists better understand developmental brain disorders, where wiring goes wrong, and may even inform future strategies for repairing damaged neural circuits. For now, the researchers are expanding their investigations to other parts of the fly brain and exploring whether similar mechanisms operate in animals such as mice.

This research represents an important milestone: not just observing how brains wire themselves, but demonstrating the ability to control that wiring in a predictable way.

Research papers:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09768-4

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09769-3