Scientists Identify Epstein–Barr Virus as a Direct Driver of Lupus

A major new study has uncovered one of the strongest links ever found between a common virus and the autoimmune disease systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The research, led by scientists at Stanford University and published in Science Translational Medicine, shows that the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)—a virus carried silently by most people—can directly reprogram a small group of immune cells and trigger the widespread immune attacks seen in lupus. Researchers describe this as one of the most impactful discoveries in lupus research, and the evidence presented is both detailed and compelling.

This article breaks down exactly what the study found, how EBV manipulates the immune system, why only some people develop lupus despite almost everyone carrying this virus, and what this means for future treatments. I’m also adding extra background information about lupus, EBV, and autoimmune diseases to give readers a complete picture of why this discovery matters.

How a Common Virus Becomes a Trigger for Lupus

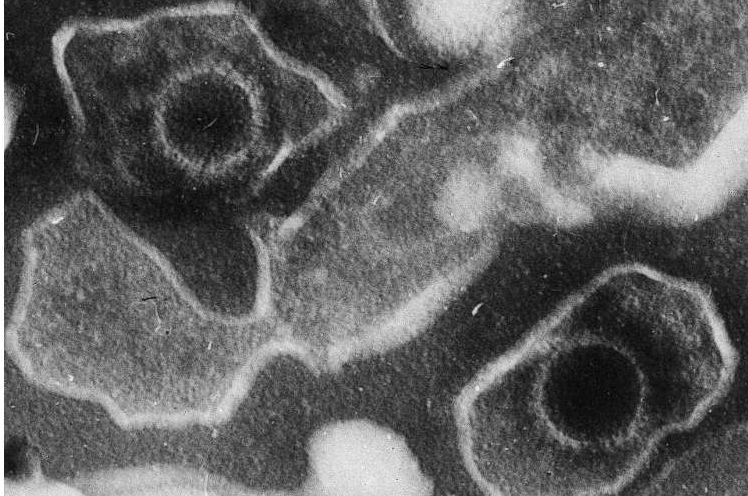

EBV infects roughly 19 out of 20 adults. Most people encounter it in childhood or adolescence through saliva—sharing utensils, drinking from the same glass, or kissing. Sometimes it causes infectious mononucleosis, also known as “the kissing disease.” After the initial infection, the virus never leaves the body. Instead, it hides in the nuclei of infected B cells, a type of immune cell responsible for making antibodies and presenting antigens to other immune cells.

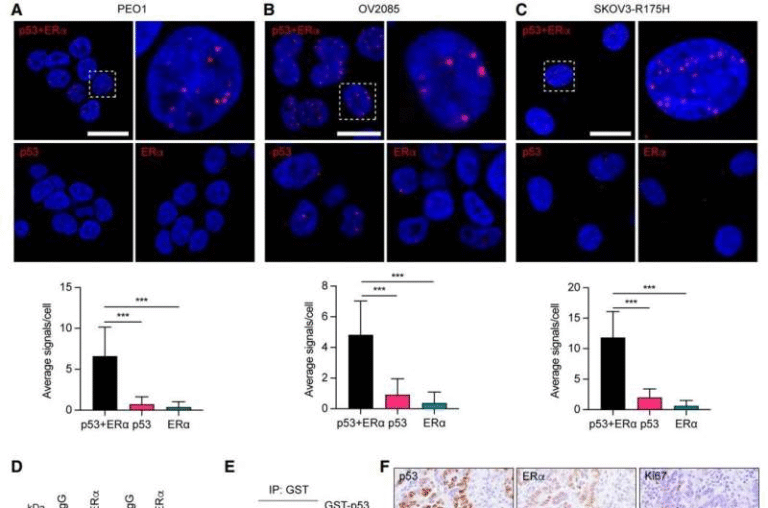

The research team developed a high-precision sequencing method that can identify exactly which B cells contain the EBV genome, something previous technology could not reliably do. Using this method, they discovered that:

- In healthy individuals, fewer than 1 in 10,000 B cells carry EBV.

- In people with lupus, this number shoots up to about 1 in 400—a 25-fold increase.

This difference alone is striking, but the study goes much deeper than numbers. The scientists found that these EBV-infected B cells are not just passive viral shelters—they are biologically altered in ways that push the immune system toward autoimmunity.

EBV’s Molecular Switch: How the Virus Rewires B Cells

One of the most important discoveries in this study is the role of an EBV protein called EBNA2. Even when EBV is in a latent, quiet state, EBNA2 can be occasionally produced. When that happens, it works like a genetic switch, turning on human genes involved in inflammation and antigen presentation.

The researchers found that EBNA2 activates several key human genes, including:

- ZEB2 – a transcription factor involved in immune cell programming

- TBX21 (T-bet) – another transcription factor linked to inflammatory responses

- Genes that convert B cells into professional antigen-presenting cells

These transformed B cells adopt a highly active, inflammatory identity. They begin displaying nuclear materials—DNA and proteins from the cell’s own nucleus—as antigens. When helper T cells encounter these “self-antigens,” they become activated and start recruiting large numbers of autoreactive B cells and killer T cells. These recruited cells do not need to be infected with EBV themselves. Once the cascade begins, the immune system becomes misdirected toward self-tissues.

This chain reaction leads to lupus, where antibodies target the nuclei of cells across the body, damaging organs including the skin, kidneys, joints, heart, and nerves.

Why Almost Everyone Has EBV but Only Some Get Lupus

One natural question arises: If EBV is almost universal, why does lupus only affect a few million people worldwide?

Researchers suggest several possibilities:

- Certain EBV strains may be more likely to reprogram B cells into inflammatory states.

- Genetic predisposition might determine which individuals respond abnormally to EBV.

- Hormonal factors likely contribute, since nine out of ten lupus patients are women.

- Environmental triggers or secondary infections might push the immune system past a tipping point.

Current research is examining whether distinct variants of EBV are more potent at producing EBNA2 or activating immune pathways.

The Antinuclear Antibody Problem: How Lupus Actually Forms

Lupus is defined by the presence of antinuclear antibodies, which target proteins and DNA inside cells. These antibodies arise when autoreactive B cells wake up and begin producing harmful immune molecules. Interestingly, around 20% of all B cells in the body are naturally autoreactive, but most remain inactive throughout life.

The EBV-driven reprogramming of B cells appears to change that. By activating helper T cells and turning EBV-infected B cells into hyperactive antigen-presenting units, the virus awakens these dormant autoreactive B cells. Once activated, they produce antinuclear antibodies and help set off the chronic autoimmune attacks that characterize lupus.

What Makes This Study Stand Out

This research is significant for several reasons:

- It provides a mechanistic explanation for a long-suspected connection between EBV and lupus.

- It demonstrates actual viral activity in human B cells, not just correlation.

- It uses sophisticated tools such as single-cell sequencing, epigenetic profiling, and antibody analysis.

- It shows that EBV-infected B cells in lupus patients produce antibodies that bind to nuclear antigens—exactly what defines lupus.

This level of molecular detail makes the study one of the strongest arguments yet that EBV is not just correlated with lupus but may actually cause it in many cases.

Could EBV Play a Role in Other Autoimmune Diseases?

The researchers believe this viral mechanism might extend beyond lupus. Autoimmune diseases that have shown hints of EBV involvement include:

- Multiple sclerosis (MS)

- Rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

- Crohn’s disease

All of these conditions involve immune dysregulation, and several studies have already identified EBV footprints in the immune cells of affected individuals. The new findings may help unify autoimmune research by revealing common viral triggers.

What This Means for Future Treatments

This discovery could influence several areas of medicine:

1. EBV Vaccines

Multiple companies are working on EBV vaccines, and clinical trials are underway. However, a vaccine would need to be administered early in life, as vaccines cannot remove EBV after infection.

2. Targeted lupus treatments

Instead of broadly suppressing the immune system, future therapies might:

- Target EBV-infected B cells specifically

- Block or neutralize EBNA2

- Prevent the reprogramming of autoreactive cells

- Interrupt the cascade between infected B cells and helper T cells

This approach could reduce side effects compared to current treatments, which often weaken immunity across the board.

3. Diagnostic breakthroughs

The new EBV detection method could help doctors identify patients who are at higher risk of developing lupus long before symptoms appear.

Extra Background: What Is EBV and Why Is It So Common?

The Epstein–Barr virus is a member of the herpesvirus family, related to viruses that cause chickenpox and cold sores. Once EBV infects someone, it stays in the body permanently. Most adults carry the virus without knowing it.

Key facts about EBV:

- It spreads through saliva.

- It infects B cells and remains dormant.

- It can reactivate occasionally without symptoms.

- It is one of the most successful human viruses ever identified.

EBV’s ability to hide in immune cells makes it incredibly difficult to eliminate—and potentially dangerous when something goes wrong with immune regulation.

Extra Background: What Is Lupus?

Lupus is a chronic autoimmune disease where the immune system attacks the body’s own tissues. Symptoms vary widely and may include:

- Fatigue

- Joint pain

- Skin rashes

- Kidney inflammation

- Heart and lung involvement

- Neurological symptoms

About five million people worldwide live with lupus. Most can lead normal lives with treatment, but about 5% may face life-threatening complications.

Research Source

Epstein–Barr virus reprograms autoreactive B cells as antigen presenting cells in systemic lupus erythematosus

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/scitranslmed.ady0210