Scientists Reverse Aging in Blood Stem Cells by Correcting Lysosomal Dysfunction

Researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai have uncovered a detailed and compelling mechanism for reversing aging in blood-forming stem cells. Their work centers on a problem that becomes increasingly significant as we grow older: the gradual decline of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), the rare and long-lived cells in bone marrow responsible for producing every blood and immune cell in the body. As these stem cells age, they lose their ability to regenerate, leading to reduced immunity, higher infection risk, and age-associated blood disorders. The new study reveals how these aging cells can be restored to a more youthful, functional state by targeting a specific type of cellular dysfunction.

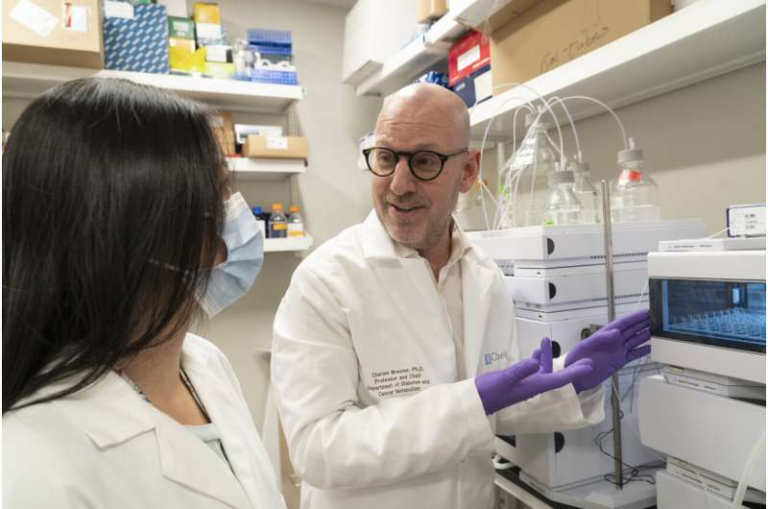

The team, led by Saghi Ghaffari, MD, PhD, investigated why aged HSCs become metabolically unstable and less capable of self-renewal. Their findings point to the lysosome — the cell’s internal recycling and degradation system — as a central culprit. Lysosomes normally break down waste materials like proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids, while also storing nutrients and playing key roles in regulating both catabolism and anabolism. But in aged stem cells, lysosomes were found to be hyperacidic, depleted, damaged, and unusually hyperactive, creating a cascade of dysfunction across metabolism, epigenetics, and immune signaling.

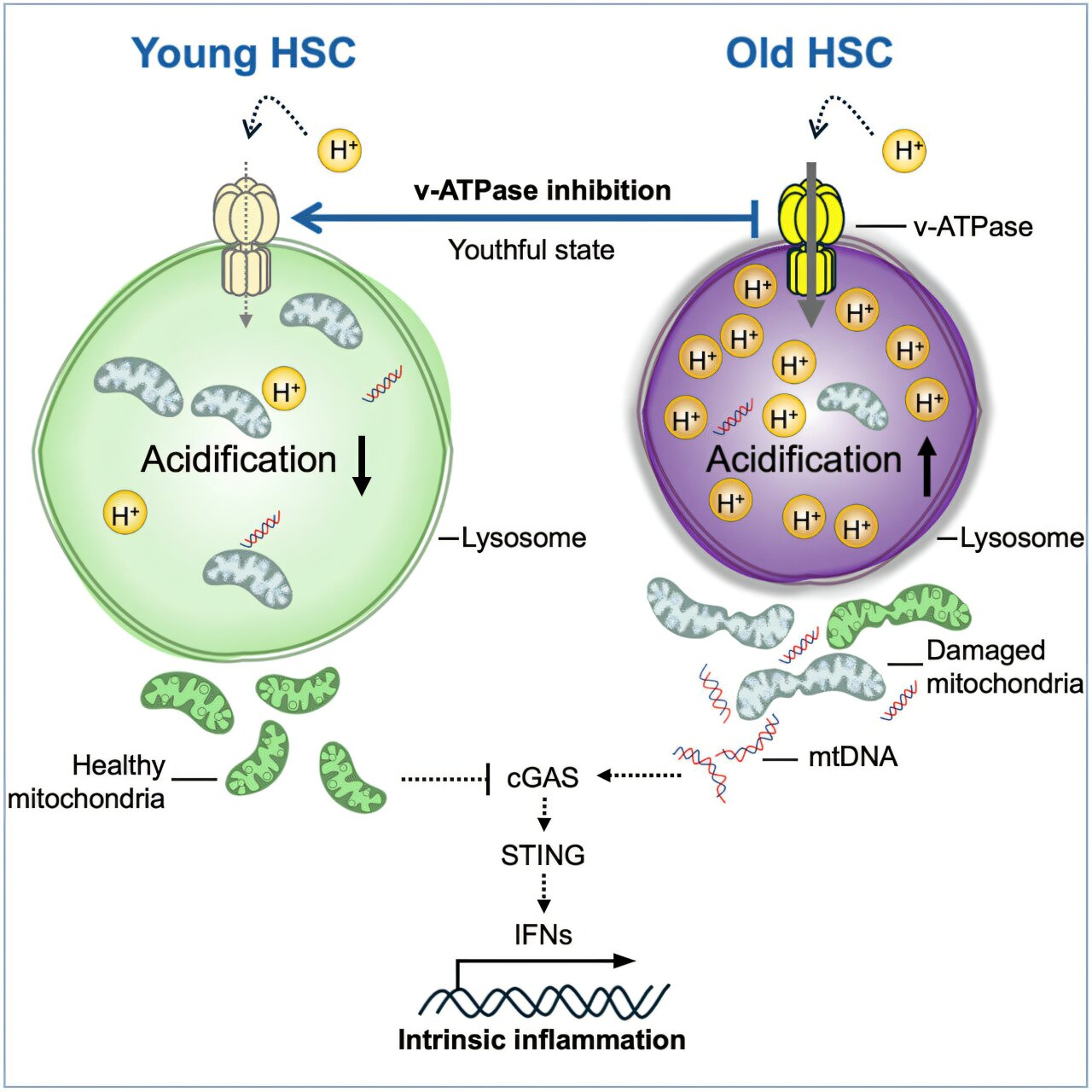

Using single-cell transcriptomics and rigorous functional assays, the researchers demonstrated that suppressing lysosomal hyperactivation with a specific vacuolar ATPase inhibitor restores lysosomal integrity. Once this hyperactivity was corrected, old blood stem cells began to behave like young ones. They regained strong regenerative potential, restored mitochondrial function, balanced their blood-cell-producing abilities, and normalized their metabolism. Inflammation levels dropped, and the cells stopped emitting inflammatory signals that typically contribute to tissue aging.

One of the most striking results came from ex vivo treatment. When old stem cells were removed from mice, treated with the lysosomal inhibitor in a lab setting, and then transplanted back into the animals, their blood-forming capacity increased by more than eightfold. This demonstrates that correcting lysosomal dysfunction is not just a superficial fix — it fundamentally rejuvenates the cells’ internal machinery. The improved lysosomal function also reduced harmful activation of the cGAS-STING pathway, an immune signaling route triggered when mitochondrial DNA leaks into the cytosol, a common feature in aged cells that drives inflammation and accelerates aging.

The implications of this work extend beyond academic understanding. If lysosomal dysfunction is indeed a central driver of stem cell aging, as the researchers propose, then targeting this pathway could open up new therapeutic routes. Such treatments may one day improve immune function in older adults, increase the success rate of stem cell transplants, enhance conditioning for gene therapy, and reduce the risk of age-related blood disorders such as clonal hematopoiesis. This condition, which increases with age, is considered a premalignant state and raises the risk of blood cancers and systemic inflammation.

Age is also the most significant risk factor in cancer development. According to the American Cancer Society, older age and smoking are the two most important risk contributors to overall cancer risk. Data from the National Cancer Institute shows that the median age of cancer diagnosis is 67, highlighting how closely tied aging biology is to disease vulnerability. The Mount Sinai findings fit squarely into this broader context: if stem cell aging can be reversed, it may influence not only immunity but also the development of age-associated cancers.

The team is now expanding its work to explore whether lysosomal dysfunction in aged HSCs may contribute to the formation of leukemic stem cells, offering a potential mechanistic link between normal aging and cancer. If confirmed, this would provide an even stronger case for therapeutic targeting of lysosomal pathways.

Below are additional sections that give readers more background on the topic, helping to expand the article toward a fuller understanding of the biology involved.

Understanding Hematopoietic Stem Cells

HSCs are among the most essential and tightly regulated cells in the body. They reside in the bone marrow and maintain blood production throughout life. Unlike most cells, they can both self-renew and differentiate into a wide range of specialized blood and immune cells. When these stem cells become dysfunctional with age, a person becomes more susceptible to anemia, infections, autoimmune issues, and cancers. The discovery that aged HSCs can revert to healthier functioning demonstrates that their decline is not predetermined or irreversible.

Why Lysosomes Matter in Aging

Lysosomes are often described as the cell’s recycling plant, but their influence is broader. They regulate nutrient sensing, energy balance, waste clearance, and autophagy — all processes that shift dramatically in aging. Hyperactive lysosomes, like those found in old HSCs, degrade cellular components too rapidly or inefficiently, destabilizing the larger metabolic environment of the cell. The hyperacidity that develops alters enzyme activity and prevents proper recycling, contributing to mitochondrial damage and inflammation. By slowing lysosomal activity to youthful levels, the Mount Sinai team restored a whole network of cellular processes.

The Role of the cGAS-STING Pathway in Inflammation and Aging

One hallmark of aging is chronic inflammation, sometimes called inflammaging. This is partly driven by the inappropriate activation of the cGAS-STING pathway, which detects DNA in places it should not be, such as mitochondrial DNA in the cytosol. When lysosomes fail to clear damaged mitochondria properly, mitochondrial DNA leaks, activating immune pathways that push cells into an inflamed state. The study showed that correcting lysosomal processing reduces this activation, restoring a healthier, low-inflammation environment inside the cell.

Potential Future Therapies

While promising, the current findings are based on mouse models. Translating them into human clinical treatments will require more research to understand dosing, safety, long-term effects, and potential off-target impacts. Still, the concept of rejuvenating stem cells outside the body and reinfusing them offers a pathway that aligns closely with existing procedures used in bone marrow and gene therapy settings. If therapies can improve the functionality of older adults’ stem cells before transplantation, clinical outcomes could improve significantly.

Aging Research and Broader Implications

This study adds to a growing body of work showing that aging at the cellular level is often reversible. From telomere length restoration to mitochondrial repair, epigenetic reprogramming, and metabolic resetting, multiple fields are converging on the idea that biological age can be modified. The lysosomal approach is particularly compelling because it acts upstream of many age-related defects. If the lysosome is restored to proper activity, many downstream aging processes improve automatically.

Mount Sinai’s research marks a clear advance in our understanding of stem cell aging and offers hope for future applications in regenerative medicine, immune health, and cancer prevention. As investigations continue, lysosomal biology may become a central focus in the effort to understand and slow aging across multiple organ systems.

Research Reference:

Reversing lysosomal dysfunction restores youthful state in aged hematopoietic stem cells – Cell Stem Cell (2025)

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2025.10.012