Scientists Uncover How the Brain Tracks Time to Control Precise Movements

Scientists from the Max Planck Florida Institute for Neuroscience have finally clarified how the brain keeps track of time to guide our movements with accuracy. Whether we’re speaking, playing a sport, or simply reaching for a cup, our actions rely on a kind of internal timer. The new research reveals that this timing system depends on the interaction between two major brain regions—the motor cortex and the striatum—working together much like an hourglass. This finding helps explain how the brain measures time without having any sensory organ devoted to detecting it.

The study, published in Nature, goes deep into how these two regions exchange signals and how disrupting either one changes the way animals behave. The team’s experiments were carried out in mice, which were trained to perform a precisely timed action. By recording neural activity and using optogenetics to temporarily silence specific brain regions, the researchers demonstrated that the motor cortex sends timing signals while the striatum accumulates them. Once the accumulated activity reaches a certain level, the movement occurs. This simple yet powerful mechanism gives the brain the flexibility to adjust timing on the fly.

Below is a clear and direct explanation of the research, its methods, its findings, and the broader significance—along with additional background information that helps readers understand how this fits into modern neuroscience.

Understanding the Brain’s Internal Timer

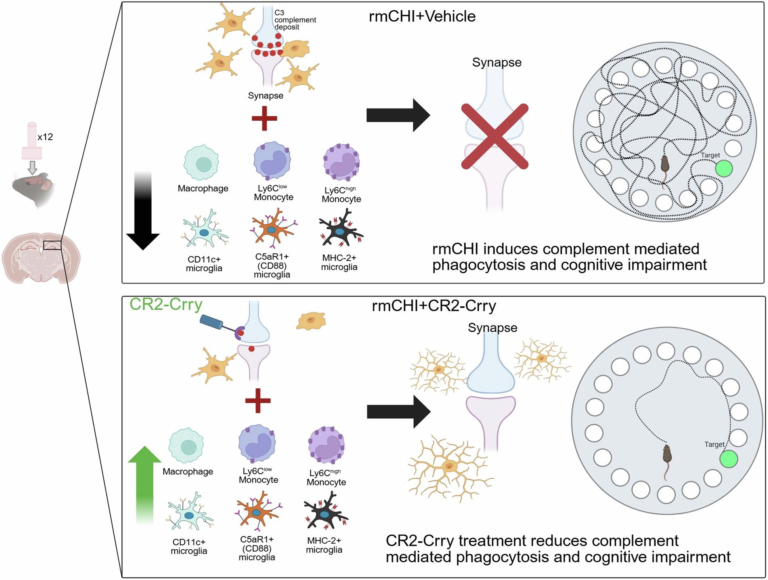

Scientists have long suspected that the brain contains an adjustable timing mechanism for controlling actions, but the exact implementation was unclear. Damage to either the motor cortex or the striatum in humans and animals is known to cause movement timing problems, particularly in disorders such as Parkinson’s and Huntington’s disease, which affect these same regions. This hinted that both areas played a role, but how they interacted remained unknown.

In this new study, the researchers focused on revealing the contributions of each region. They emphasized that even though we have no dedicated sensory organ for time, the brain clearly keeps track of time internally. The goal of the research was to uncover how this happens at the level of neural circuits.

What the Scientists Did in the Study

To measure time-related brain activity, the scientists trained mice to perform a simple task: the mice had to lick a spout to receive a reward, but only after waiting a specific amount of time, such as 1 second. This waiting period created an ideal situation to observe how the brain tracks time.

Once the mice learned the task, the researchers recorded the electrical activity of thousands of neurons in both the motor cortex and the striatum. They found that both regions displayed patterns of activity that changed over time, suggesting involvement in measuring the delay before the lick.

To go further, they used a technique called optogenetics, which allows researchers to control neural activity with flashes of light. By briefly silencing either the motor cortex or the striatum, they could test how each region contributed to the timer.

The Hourglass Mechanism Explained

The results point to a model where the motor cortex and striatum behave like the two parts of an hourglass.

- The motor cortex acts like the top of the hourglass, sending a steady stream of signals downward.

- The striatum acts like the bottom, accumulating those signals over time—similar to sand piling up.

- When the accumulation reaches a threshold, the movement (in this case, licking the spout) is triggered.

This mechanism is simple but extremely flexible. It can adjust to different timing demands by changing how quickly the accumulation happens or how much needs to accumulate.

What Happens When the Motor Cortex or Striatum Are Silenced

The optogenetic experiments were crucial to understanding how the system works:

- Silencing the motor cortex paused the flow of signals, which caused the timing accumulation in the striatum to pause as well. The mice then performed their lick later than usual. This showed that the motor cortex is responsible for driving the timer forward.

- Silencing the striatum had a very different effect: it reset the timer completely. After the interruption, the mice took even longer to lick, showing that the accumulated activity had been erased. This is like flipping the hourglass over.

These findings clearly demonstrated the distinct roles of each brain region. One provides the signals; the other tracks their accumulation over time.

Why These Findings Matter

This discovery is important for multiple reasons. First, it provides a detailed explanation of how the brain measures time to control behavior—something that has puzzled neuroscientists for decades. Second, it directly links this mechanism to brain regions that malfunction in common neurological disorders.

People with Parkinson’s disease, for example, often struggle with initiating movements or timing them accurately. Since the striatum and motor cortex are both affected in Parkinson’s, understanding the timing circuit might offer clues for improving treatments. The researchers hope that mapping these interactions will eventually lead to strategies for restoring movement abilities in people with motor disorders.

In the broader scientific context, the study adds to a growing body of evidence that timing in the brain does not rely on a single “clock” but emerges from interactions among brain regions. This makes the system more flexible and adaptable to different kinds of behavior.

Additional Background: How Animals and Humans Perceive Time

The brain’s perception of time is one of its most mysterious functions. Unlike vision, hearing, or smell, time is not detected by specialized receptors. Instead, the brain relies on internal dynamics.

Across species, several theories have been proposed to explain how the brain tracks time:

- Population clocks, where large groups of neurons change their firing patterns over time.

- Oscillation theories, where rhythmic activity helps coordinate timing.

- Integrator models, like the hourglass found in this study, where signals accumulate until a threshold is reached.

The new findings support the integrator model, showing that the brain uses accumulation of signals to measure time in a way that is both accurate and flexible.

Understanding time perception is essential because timing is built into almost everything we do. Speaking requires precise timing of syllables and pauses. Playing an instrument requires coordinating hand movements down to fractions of a second. Even simple tasks like walking require timed muscle activation.

Additional Background: The Striatum and Motor Cortex in Movement Control

The motor cortex is responsible for planning and generating voluntary movement. It sends commands to muscles but also plays a major role in preparing movements and organizing sequences of action.

The striatum, part of the basal ganglia, is known for its role in initiating movements, controlling movement vigor, and learning action patterns. It receives dense input from the motor cortex, linking intention to action.

In neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s, the striatum’s function is disrupted due to lack of dopamine. This leads to delays, slowness, and difficulty initiating movements—which aligns with the timer-resetting role discovered in this research.

The new hourglass model underscores how closely these two brain regions work together, forming a loop that supports flexible motor timing.

Research Reference

Integrator dynamics in the corticobasal ganglia loop for flexible motor timing — Nature (2025)

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09778-2