Shroom3 Mutation Linked to Kidney Scarring Opens the Door to a New Precision Drug Target

Nearly 1 in 7 adults in the United States lives with chronic kidney disease (CKD), a condition that often progresses quietly until significant and sometimes irreversible damage has already occurred. While diabetes and high blood pressure are widely recognized as the main drivers of kidney failure, scientists have long struggled with a lingering question: why do some people’s kidneys deteriorate much faster than others, even when they share the same risk factors?

A new study from Yale University, led by physician-scientist Dr. Madhav Menon, offers a compelling answer. The research points to a common genetic mutation in the Shroom3 gene that appears to act as a silent accelerator of kidney scarring. More importantly, the study identifies a precise molecular target that could eventually lead to new drugs designed to slow or prevent kidney damage.

A Common Gene With an Outsized Impact

The Shroom3 gene plays an important role in maintaining the structure of kidney cells. What makes this discovery especially striking is how common the risky genetic variant is. Roughly 40% of people in the United States carry this mutation, making it far from rare.

Rather than causing kidney disease on its own, the Shroom3 mutation works as a genetic predisposition. In people who already have diabetes, hypertension, or other forms of kidney stress, the mutation raises the likelihood of developing CKD and speeds up disease progression. In other words, it adds an extra layer of risk on top of existing conditions.

This distinction matters. The mutation does not act like a traditional disease trigger but instead amplifies damage after injury, helping explain why two patients with similar health profiles can experience very different kidney outcomes.

Understanding Kidney Scarring and Fibrosis

A central feature of chronic kidney disease is fibrosis, the gradual buildup of scar tissue inside the kidneys. Over time, this scarring replaces healthy, functioning tissue, reducing the kidneys’ ability to filter blood and regulate essential processes like fluid balance and waste removal.

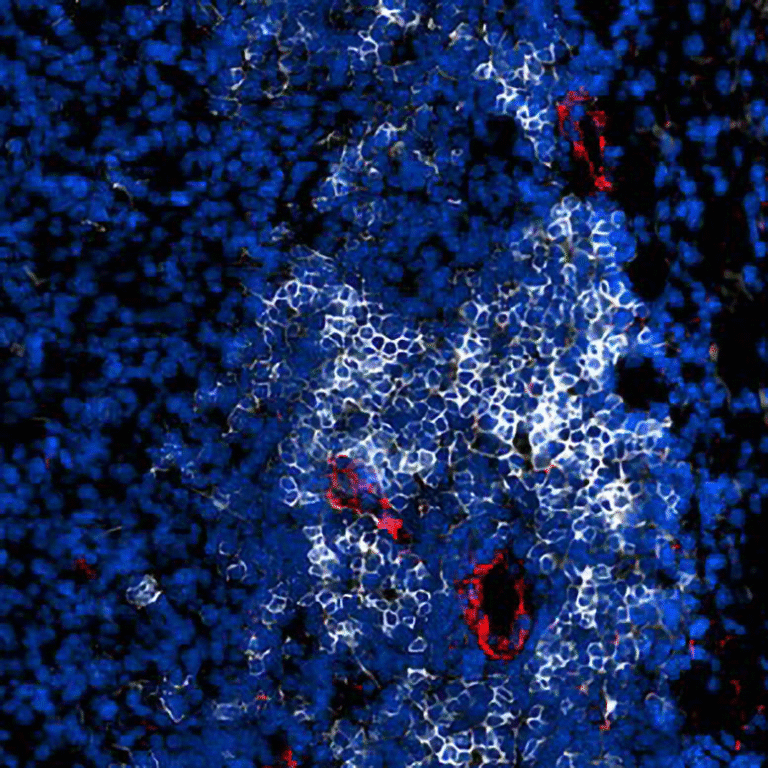

The Yale team found that the Shroom3 mutation leads to overproduction of the Shroom3 protein in specific kidney cells. This excess protein becomes problematic after kidney injury, regardless of the original cause. Instead of supporting normal cell structure, too much Shroom3 activates fibrotic pathways, accelerating scarring and long-term damage.

This helps clarify why kidney disease can worsen even after blood sugar or blood pressure is brought under control. The genetic background of the patient still influences how the kidneys respond to stress.

Separating the Good From the Bad

One of the most important aspects of this research is its precision-focused approach. Shroom3 is not inherently harmful. In fact, it plays beneficial roles in maintaining kidney cell architecture. Blocking the entire protein could therefore disrupt normal kidney function and lead to unintended consequences.

Instead of shutting down Shroom3 altogether, the researchers focused on dissecting the protein’s structure. Their hypothesis was simple but powerful: different regions of the protein may be responsible for different effects.

Their experiments confirmed this idea. A specific region of Shroom3 was found to interact with a downstream signaling partner that drives fibrosis. By targeting only that interaction, the researchers were able to reduce kidney scarring without interfering with the protein’s helpful functions.

In animal models, selectively blocking this fibrotic interaction prevented scarring, preserved kidney structure, and improved overall kidney health.

A New Drug Target Takes Shape

The study represents a proof of concept for a new class of treatments. Rather than broadly suppressing inflammation or fibrosis, future therapies could precisely interrupt the Shroom3-driven scarring pathway.

This strategy aligns closely with the principles of precision medicine, where treatments are tailored to a patient’s genetic profile. Because the Shroom3 mutation is so widespread, a drug targeting this pathway could potentially benefit millions of people at elevated risk for CKD.

Dr. Menon’s lab is now refining the drug compounds, testing their safety and potency in additional experimental models. The next steps include studies using human kidney organoids, lab-grown mini-kidneys that closely mimic real human tissue.

If development continues as planned, human clinical trials could begin within the next five years.

Why This Matters for Patients

For patients living with or at risk for chronic kidney disease, the implications are significant. Current treatments largely focus on managing contributing conditions like diabetes and hypertension. While effective, these approaches do not directly address why certain kidneys scar more aggressively.

This research provides hope that future therapies could slow disease progression at its root, especially for genetically vulnerable individuals. It also opens the door to genetic screening as part of routine kidney care, helping doctors identify high-risk patients earlier and intervene more effectively.

The work has already resonated with patients who know they carry Shroom3 variants and are searching for answers. For them, this study represents a potential turning point from risk awareness to actionable treatment options.

The Bigger Picture of Precision Nephrology

This discovery fits into a broader shift toward precision nephrology, a growing field that aims to tailor kidney disease prevention and treatment based on genetics, molecular pathways, and individual biology.

Rather than treating CKD as a single disease, researchers are increasingly recognizing it as a collection of overlapping conditions with distinct drivers. By identifying mutation-specific mechanisms like Shroom3-related fibrosis, scientists can design therapies that are more targeted, safer, and more effective.

This approach also helps explain why many past kidney drugs have failed in clinical trials. Without accounting for genetic differences, treatments may work well for some patients but show limited benefits across diverse populations.

Additional Background: Why Fibrosis Is So Hard to Treat

Kidney fibrosis has long been a difficult target for drug development. Fibrotic pathways are often shared across multiple organs, meaning that blocking them can cause side effects in the heart, lungs, or liver.

What makes the Shroom3 discovery especially promising is its kidney-specific context. By targeting a protein interaction that is particularly relevant in kidney cells, researchers may be able to avoid the systemic risks that have plagued earlier antifibrotic therapies.

This specificity could mark a new era in how chronic kidney disease is treated, moving away from generalized suppression and toward smart, pathway-focused intervention.

Looking Ahead

While the research is still in its early stages, it represents one of the clearest examples yet of how genetics can guide drug development in kidney disease. With continued progress, therapies based on this work could eventually help slow or even halt kidney scarring in high-risk individuals.

For a condition that affects tens of millions of people and often progresses silently, that possibility is hard to ignore.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67854-7