Small Molecules Could Treat Crohn’s Disease by Mimicking a Protective Gene Variant

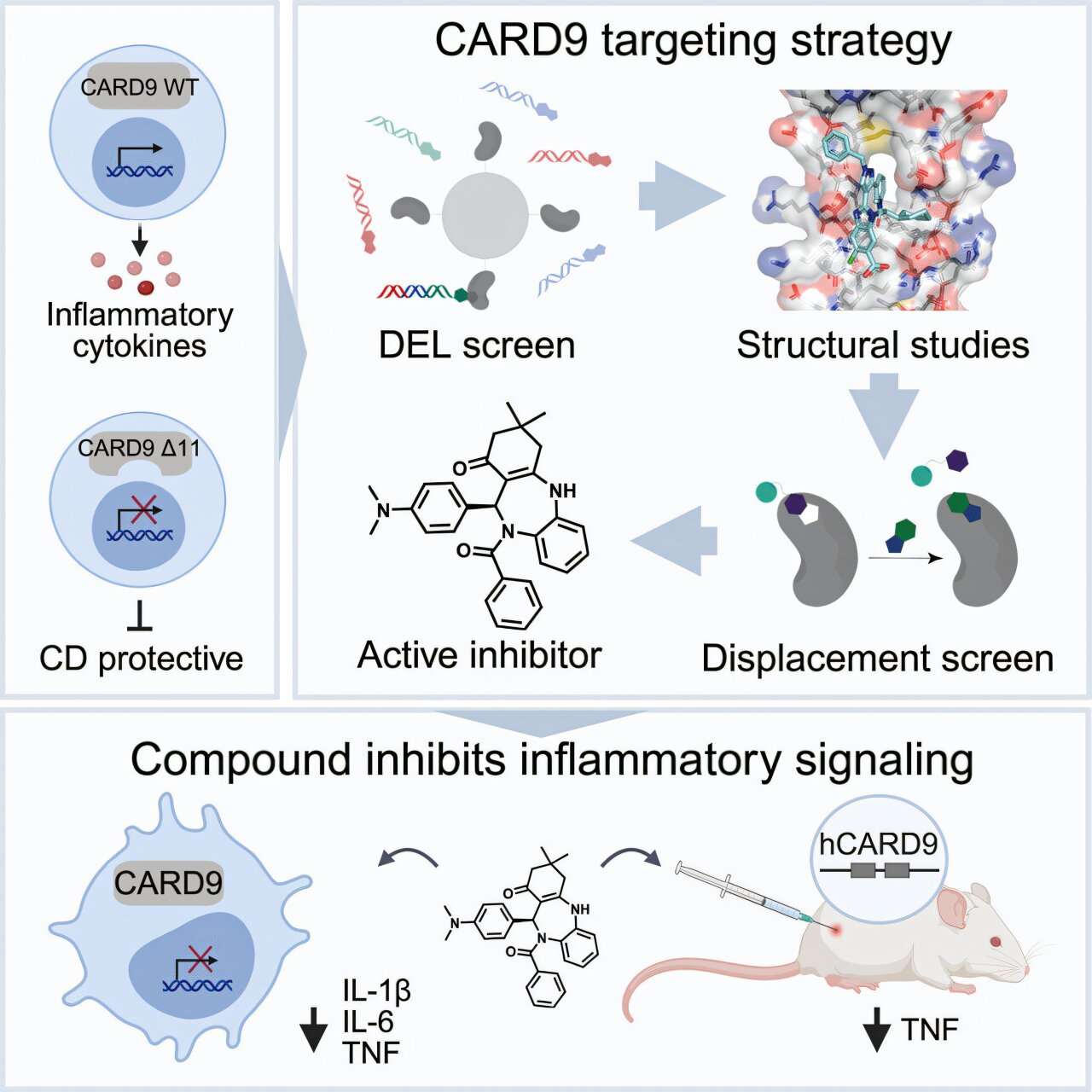

Scientists may be closing in on a new way to treat Crohn’s disease and other inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) by learning from genetics rather than fighting against it. A new study published in Cell describes how researchers have developed small-molecule drug candidates that imitate the effects of a rare, naturally occurring protective gene variant. This approach could eventually offer a safer and more targeted treatment option for millions of people living with chronic gut inflammation.

Inflammatory bowel disease, which includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, affects an estimated 3 million people in the United States alone. These conditions are driven by long-term inflammation of the digestive tract, often leading to pain, diarrhea, fatigue, and progressive tissue damage. While existing treatments aim to suppress the immune system or block inflammatory signals, they don’t work for everyone and can come with significant side effects.

What makes this new research especially interesting is that it flips the usual logic of drug discovery. Instead of asking how to shut down inflammation broadly, the scientists asked a simpler and smarter question: why are some people naturally protected from IBD in the first place?

The Protective Role of the CARD9 Gene

The story begins with a gene called CARD9, which plays an important role in immune signaling, particularly in how the body responds to microbes in the gut. In 2011, researchers at the Broad Institute, led by scientists including Ramnik Xavier and Mark Daly, analyzed the genomes of tens of thousands of people with and without IBD. Their work uncovered dozens of genes linked to Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, with CARD9 standing out as especially important.

Most people carry common versions of CARD9 that are associated with higher risk of inflammatory bowel disease. However, a small number of people have a rare variant of this gene that truncates the CARD9 protein. Surprisingly, individuals with this shortened version are far less likely to develop IBD.

At first glance, this seemed puzzling. CARD9 is involved in activating immune responses, so completely disabling it would be expected to cause problems, especially in fighting infections. And indeed, shutting off CARD9 entirely is not safe. But the protective variant doesn’t eliminate CARD9’s function. Instead, it allows the initial immune response to occur while preventing the sustained, chronic inflammation that causes long-term damage.

Understanding that difference turned out to be crucial.

From Genetic Insight to Biological Mechanism

By 2015, Xavier’s team had figured out how the protective CARD9 variant works. The shortened protein essentially acts as a brake on inflammation, stopping immune signals from staying switched on for too long. This insight revealed that a specific region of the CARD9 protein, known as the coiled-coil domain, was responsible for this effect.

This discovery also highlighted a major challenge. CARD9 is a scaffolding protein, meaning it helps organize other proteins rather than performing a single enzymatic function. Proteins like this are often labeled “undruggable” because they lack obvious pockets where small molecules can bind.

Rather than giving up, the researchers decided to tackle this challenge head-on.

Screening Billions of Molecules

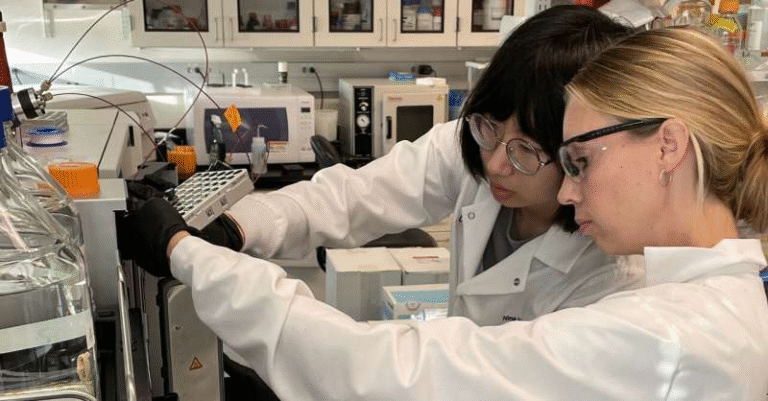

In collaboration with Johnson & Johnson Innovative Medicine (formerly Janssen), the team launched an ambitious drug discovery effort. They screened an astonishing 20 billion molecules to see whether any could bind to CARD9.

Early results were discouraging. Some molecules could bind to the protein, but they didn’t actually reduce inflammation. Instead of abandoning the project, the researchers took a more creative approach.

They solved the first-ever crystal structure of CARD9 bound to a small molecule. This structural breakthrough confirmed that the coiled-coil domain could, in fact, be targeted. The team then turned one of the binding molecules into a fluorescent probe, allowing them to test additional compounds that could displace it and bind more effectively.

This binder-first strategy proved to be the turning point. It not only showed that CARD9 was druggable after all, but also pinpointed the exact binding site needed to block inflammatory signaling.

Promising Results in Cells and Mice

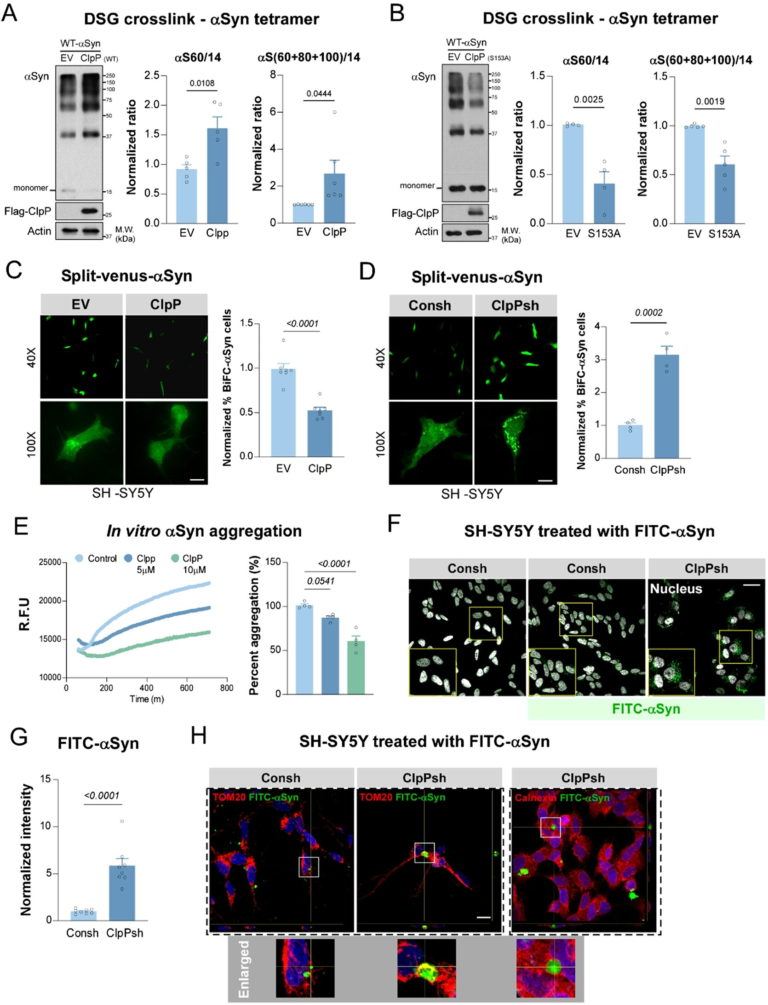

Using this refined screening method, the researchers identified a new class of small molecules that selectively block CARD9-driven inflammation. In human immune cells, these compounds reduced inflammatory signaling without disrupting other critical immune pathways.

The results were even more encouraging in animal studies. In mice engineered to carry the human version of CARD9, treatment with these drug candidates led to a significant reduction in gut inflammation. Importantly, the drugs mimicked the effects of the protective gene variant rather than completely shutting down immune function.

While these molecules still need further optimization before human trials can begin, the findings demonstrate a full genetics-to-therapeutics pipeline—from discovering a protective mutation to designing drugs that reproduce its benefits.

Why This Approach Matters

One of the most compelling aspects of this research is its focus on human genetics as a guide for drug development. Because the protective CARD9 variant already exists in healthy individuals, it provides a built-in safety signal. In other words, nature has already performed a long-term experiment showing that this pathway can be modified without causing harm.

The researchers compare this strategy to the success of PCSK9 inhibitors, cholesterol-lowering drugs inspired by genetic variants linked to naturally low cholesterol and reduced heart disease risk. That same logic now appears to be working for inflammatory diseases.

A Broader Impact on Drug Discovery

Beyond Crohn’s disease, this study offers a roadmap for tackling other conditions where genetics has identified causal genes and mechanisms. Advances in gene editing, structural biology, novel chemistry, and artificial intelligence could dramatically shorten the time it takes to move from genetic discovery to real therapies.

The study’s first authors—Jason Rush of the Broad Institute and Joshua Wertheimer and Steven Goldberg of Johnson & Johnson Innovative Medicine—highlight the power of academic–industry collaboration in addressing complex biological problems that no single group could solve alone.

Understanding Crohn’s Disease and IBD

Crohn’s disease is a chronic condition marked by inflammation that can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, from the mouth to the anus. Unlike ulcerative colitis, which is limited to the colon, Crohn’s often involves deeper layers of tissue and can lead to complications such as strictures, fistulas, and malnutrition.

Current treatments include corticosteroids, immunosuppressive drugs, and biologics that target specific inflammatory molecules. While these therapies have improved outcomes, many patients experience incomplete relief or lose responsiveness over time. A treatment inspired by protective human genetics could represent a more durable and precise solution.

Looking Ahead

The newly identified CARD9 inhibitors are not yet ready for clinical use, but they represent a major conceptual leap. Instead of broadly suppressing inflammation, future therapies may be able to fine-tune immune responses, preserving what the body needs while blocking what causes disease.

If successful, this approach could mark the beginning of a new era in treating immune-mediated diseases—one guided not just by symptoms, but by the genetic blueprints of natural protection.

Research paper: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2025.12.013