Stimulant ADHD Medications May Improve Alertness and Motivation More Than Attention, New Brain Study Finds

Stimulant medications such as Ritalin, Adderall, and other commonly prescribed drugs for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have been used for decades. They are often described as medications that help people “focus better” by directly acting on the brain’s attention systems. However, a major new brain-imaging study suggests that this long-held explanation may be incomplete — and possibly wrong.

According to new research from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, stimulant ADHD medications appear to work primarily by increasing wakefulness, arousal, and reward sensitivity, rather than directly strengthening the brain’s attention-control networks. The study, published in the journal Cell, provides one of the most detailed looks yet at how these medications affect the brain, especially in children.

How ADHD Stimulants Were Traditionally Thought to Work

For many years, scientists and clinicians believed that stimulant medications improved ADHD symptoms by acting directly on brain regions responsible for attention and executive control. These include areas such as the prefrontal cortex and the dorsal attention network, which help regulate focus, task switching, and impulse control.

Because children and adults with ADHD often struggle to stay on task, the prevailing assumption was that stimulants somehow “normalize” or strengthen these attention circuits, allowing better voluntary control over what a person pays attention to.

The new findings challenge this idea.

A Large-Scale Brain Imaging Study in Children

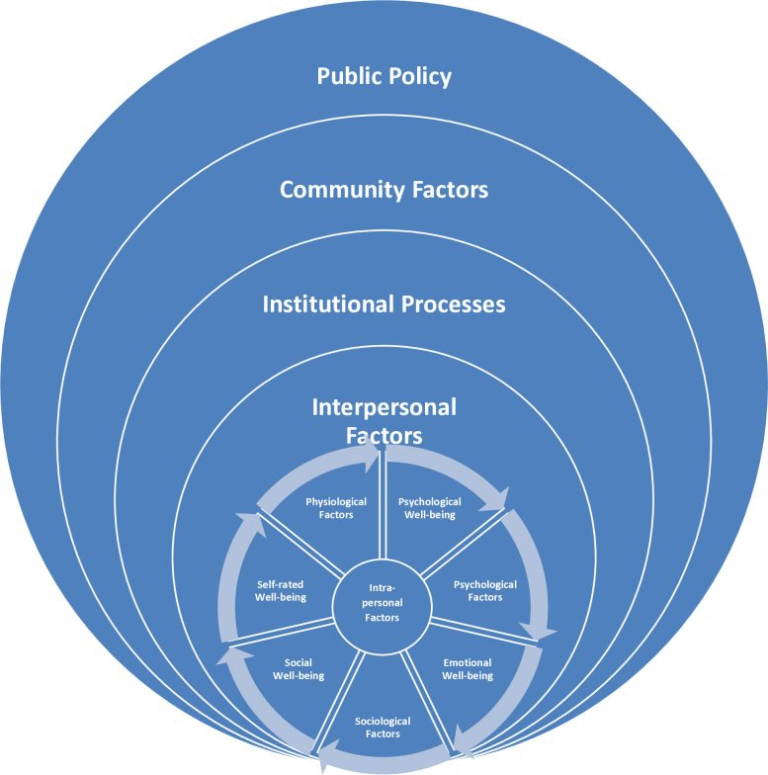

The researchers analyzed data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, one of the largest and most comprehensive pediatric brain development studies ever conducted in the United States. The ABCD study follows more than 11,000 children across multiple sites nationwide, tracking brain development, behavior, cognition, mental health, and environmental factors over time.

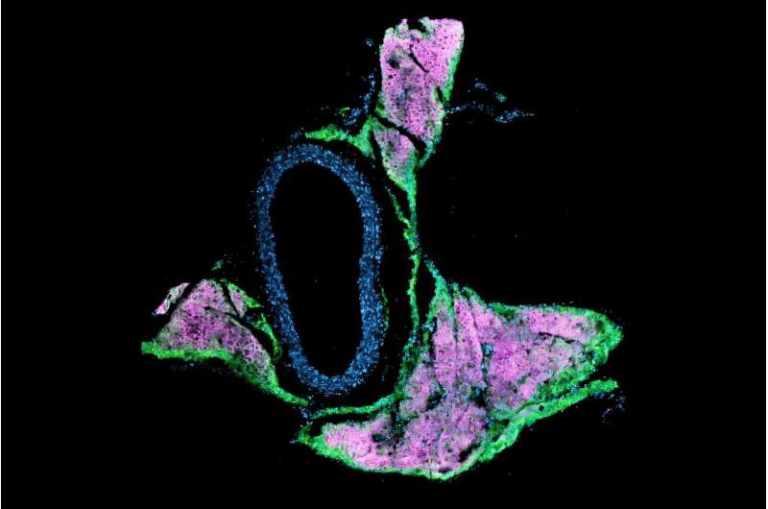

For this analysis, the team focused on resting-state functional MRI (fMRI) scans from 5,795 children aged 8 to 11. Resting-state fMRI measures patterns of brain connectivity while a person is not engaged in any specific task, offering insight into how different brain networks naturally interact.

Among these children, 337 had taken a prescription stimulant medication on the day of their brain scan, while the others had not.

What the Brain Scans Actually Showed

When researchers compared brain connectivity patterns between children who took stimulants and those who did not, the results were striking.

Children who took stimulant medications showed increased activity in brain networks related to arousal and wakefulness, as well as regions involved in reward processing and motivation. These networks help determine how alert a person feels and how rewarding or interesting a task seems.

Importantly, the scans did not show significant increases in activity within classical attention-control networks — the very regions scientists long assumed stimulants were targeting.

In simpler terms, the medications did not appear to directly “turn up” the brain’s attention systems. Instead, they seemed to make children more awake, more mentally engaged, and more motivated, which can naturally lead to better attention during tasks.

Validation in Adults Without ADHD

To make sure these findings were not limited to children or influenced by long-term ADHD-related brain differences, the researchers conducted a smaller but carefully controlled experiment in adults.

Five healthy adults without ADHD — who did not normally take stimulant medications — underwent multiple resting-state fMRI scans. Each participant was scanned before and after taking a 40 mg dose of methylphenidate, a commonly prescribed stimulant.

The adult scans showed the same pattern seen in children. After taking the stimulant, participants exhibited changes in brain connectivity primarily in arousal and reward-related networks, not attention-specific regions. This confirmed that the observed effects were caused by the medication itself rather than ADHD-related brain differences.

Why Reward and Motivation Matter for ADHD

One of the key insights from this study is the role of reward sensitivity in ADHD. Many children with ADHD struggle most with tasks they find boring, repetitive, or unrewarding — such as sitting through a lecture or completing homework.

Stimulant medications appear to make these tasks feel more rewarding, even if the tasks themselves do not change. When the brain anticipates a greater sense of reward, it becomes easier to persist, stay seated, and continue working instead of seeking stimulation elsewhere.

This mechanism may also help explain why stimulants can reduce hyperactivity, which has long seemed paradoxical. If a child finds a task more engaging, they are less likely to fidget, move around, or abandon the activity in search of something more stimulating.

The Strong Connection Between Stimulants and Sleep

One of the most important findings of the study involves sleep deprivation.

The researchers discovered that stimulant medications produced brain activity patterns that closely resembled the effects of getting sufficient sleep. In children who did not sleep enough, stimulants appeared to erase the typical brain signatures of sleep deprivation, at least temporarily.

Children with ADHD who slept less than the recommended nine or more hours per night but took stimulant medications showed better grades and improved cognitive test performance compared with sleep-deprived children who did not take stimulants.

However, stimulants did not improve performance in well-rested neurotypical children. The benefits were mainly seen in children with ADHD or those experiencing insufficient sleep.

This suggests that stimulant medications may sometimes work by masking the effects of sleep loss, rather than fixing the underlying problem.

Implications for ADHD Diagnosis and Treatment

These findings raise important questions about how ADHD is diagnosed and treated, especially in children.

Sleep deprivation can produce symptoms that closely resemble ADHD, including difficulty concentrating, impulsivity, and poor academic performance. If a child is chronically overtired, stimulant medication may appear to “help” by boosting wakefulness, even though the root cause is lack of sleep.

While this short-term boost may improve grades or behavior, the researchers warn that chronic sleep deprivation remains harmful, particularly for developing brains. Using stimulants to compensate for poor sleep could carry long-term risks that are not yet fully understood.

The authors emphasize the importance of evaluating sleep habits during ADHD assessments and considering behavioral or medical strategies to improve sleep alongside medication decisions.

Additional Context: How Stimulants Affect Brain Chemistry

Stimulant medications primarily increase levels of dopamine and norepinephrine, two neurotransmitters involved in alertness, motivation, and reward learning. These chemicals play a central role in regulating energy levels, interest, and the perceived value of tasks.

By increasing dopamine signaling, stimulants may effectively “pre-reward” the brain, making it easier to stay engaged with tasks that would otherwise feel dull or frustrating.

This broader understanding helps explain why stimulants can enhance performance in sleep-deprived individuals and why they do not necessarily improve cognition in people who are already well-rested and neurotypical.

What Still Needs to Be Studied

The researchers note several limitations. The ABCD data is observational, meaning children were not randomly assigned to take stimulants, and precise information about dosage and medication type was not available. The adult validation study was also small, though it provided strong within-person evidence.

Future studies will need to examine the long-term effects of stimulant use, especially when medications are used to compensate for chronic sleep loss. It remains unclear whether these drugs have a restorative effect on the brain or whether they could cause subtle harm over time if underlying issues like sleep deprivation are not addressed.

Research paper:

https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(25)01373-X