Structure-Based RNA Targeting Opens the Door to New Treatments for Neuromuscular Disorders

Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University have made a significant advance in RNA science that could eventually change how certain neuromuscular and neurodegenerative disorders are treated. Their work focuses on a long-standing problem in genetic diseases like myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1), where toxic RNA structures disrupt normal cellular function. By developing a highly precise, structure-based way to target these harmful RNA sequences, the team has introduced a potential path toward disease-modifying therapies rather than treatments that only manage symptoms.

The study was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) and represents years of work in nucleic acid chemistry, molecular recognition, and RNA biology.

Understanding Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1 and Related Disorders

DM1 is the most common adult-onset form of muscular dystrophy, affecting at least 1 in 2,300 people worldwide. The disease primarily causes progressive muscle weakness, muscle wasting, and myotonia, a condition where muscles have difficulty relaxing after contraction. However, DM1 is not limited to muscles alone. It can also affect the heart, lungs, eyes, endocrine system, and central nervous system, making it a complex, multisystem disorder.

At the genetic level, DM1 is caused by a mutation in the DMPK gene. This mutation involves an abnormal expansion of a short DNA sequence known as CTG repeats. In people without DM1, this CTG sequence is repeated roughly five to 35 times. In people with DM1, the repeat count can climb into the hundreds or even thousands.

When the mutated gene is transcribed into RNA, these expanded repeats fold into hairpin-like structures. These structures are not harmless. They act like molecular traps that bind and sequester essential RNA-binding proteins, particularly proteins involved in RNA splicing. Once trapped, these proteins can no longer perform their normal roles, leading to widespread errors in how many other genes are processed. The end result is a cascade of cellular dysfunction that produces the symptoms of DM1. Generally, more repeats mean more severe disease and earlier onset.

Similar RNA repeat expansion mechanisms are also involved in other serious conditions, including spinocerebellar ataxias, Friedreich’s ataxia, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Huntington’s disease, and fragile X syndrome.

Why RNA Has Been So Hard to Target

For years, researchers have tried to develop therapies that directly target toxic RNA. Traditional approaches include small-molecule drugs and antisense oligonucleotides. While promising, these methods often face major challenges.

One key issue is specificity. Many therapies struggle to distinguish between healthy RNA and disease-causing RNA, leading to off-target effects and unwanted side effects. Another challenge is delivery. Some therapies require complex chemical modifications or delivery systems to enter cells and reach their RNA targets effectively. In many cases, these limitations have slowed progress toward safe, long-lasting treatments.

This is the problem the Carnegie Mellon team set out to address.

A “Pothole-Filling” Strategy for Toxic RNA

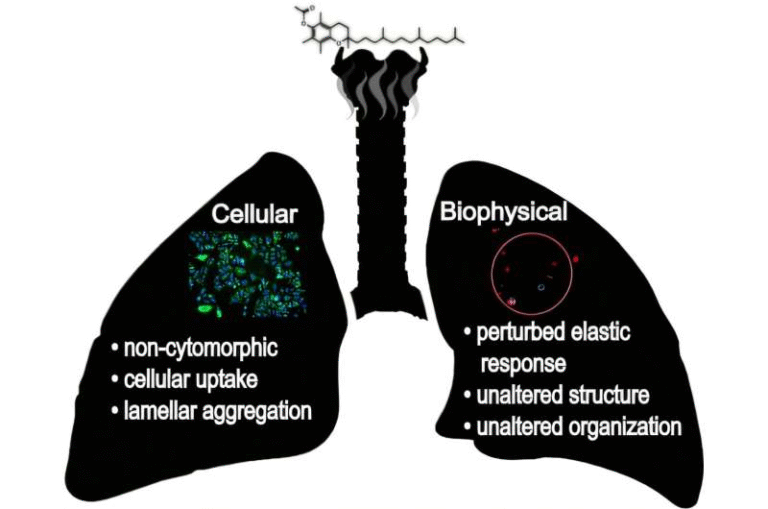

The new approach developed by the researchers has been described as a molecular “pothole filler.” Instead of trying to unwind or destroy the RNA hairpin structures, the strategy focuses on fitting precisely into the damaged regions of the RNA caused by the expanded repeats.

The team designed small, highly specific nucleic acid ligands that recognize and bind directly to the toxic RNA repeats. These ligands are engineered to interact only with the abnormal RNA structures, leaving healthy RNA untouched. This level of precision is one of the most important aspects of the work, as it dramatically reduces the risk of off-target effects.

Once bound, the ligands prevent harmful protein-RNA interactions by displacing proteins trapped within the hairpin loops. This allows those proteins to return to their normal cellular roles, potentially restoring proper RNA processing.

The Science Behind the Ligands

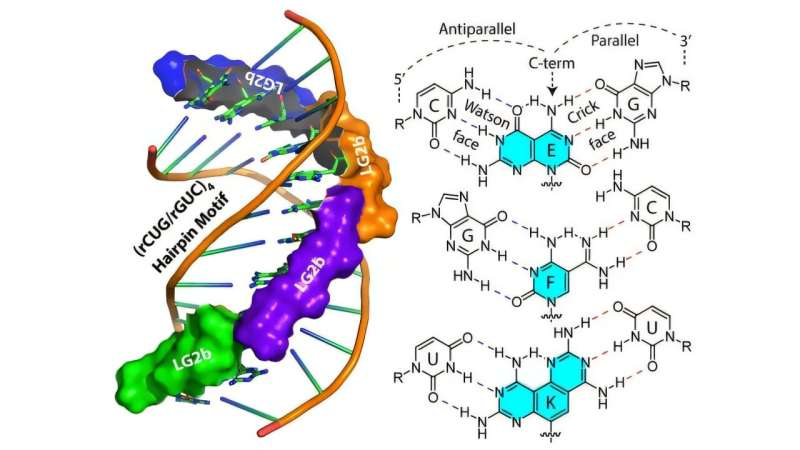

At the heart of this strategy are gamma peptide nucleic acids (γPNAs) combined with bifacial, or Janus, bases. Peptide nucleic acids are synthetic molecules that mimic DNA or RNA but have a peptide-like backbone. This gives them greater stability and programmability compared to natural nucleic acids.

The Janus bases are particularly important. Named after the two-faced Roman god Janus, these bases are designed to interact with both strands of an RNA structure at the same time. This allows the ligands to insert themselves directly between the two strands of the RNA hairpin. Unlike conventional antisense therapies, this method does not require the RNA structure to be unwound, making it especially well-suited for targeting stable, folded RNA repeats.

The research team, working within Carnegie Mellon’s Center for Nucleic Acids Science and Technology, has been a leader in PNA development for years. This study builds on earlier work that began around 2014, when efforts to create the next generation of PNA technology gained momentum.

Promising Results in Laboratory Models

In laboratory experiments, the researchers tested several ligands and identified a lead candidate known as LG2b. This molecule showed remarkable selectivity for RNA sequences containing the disease-causing rCUG repeats associated with DM1.

LG2b was able to displace toxic protein-RNA complexes without interfering with normal gene expression. Importantly, it did so without disrupting healthy RNA structures, reinforcing the idea that structure-based targeting can achieve a high level of precision.

While these results are still preclinical, they represent a crucial proof of concept. The team is now focused on optimizing the ligands, improving cellular uptake, refining drug delivery strategies, and testing efficacy in more advanced disease models.

Broader Implications for RNA Medicine

This research goes beyond DM1. Because many genetic disorders are driven by toxic RNA repeats, the same structure-based approach could potentially be adapted to treat a wide range of conditions. Diseases such as spinocerebellar ataxias, Friedreich’s ataxia, ALS, Huntington’s disease, and fragile X syndrome all involve repeat expansions that form abnormal RNA structures.

More broadly, the study highlights the growing importance of RNA as a therapeutic target. As scientists continue to uncover how RNA structure influences disease, precision tools like these ligands may become a cornerstone of future treatments.

Looking Ahead

There is currently no effective cure or disease-modifying therapy for DM1, and treatment options remain limited to symptom management. While this new approach is still in the research phase, it represents a meaningful step toward therapies that address the root cause of RNA-repeat disorders rather than their downstream effects.

By combining deep knowledge of RNA structure with innovative molecular design, the Carnegie Mellon team has provided a powerful example of how structure-based RNA targeting could reshape the treatment landscape for neuromuscular and neurodegenerative diseases.

Research Paper Reference:

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2507065123