Targeting Aberrant Learning Could Improve Parkinson’s Treatment and Reduce Levodopa Side Effects

Parkinson’s disease has long been treated by focusing on one central problem: the loss of dopamine-producing neurons in the brain. For decades, levodopa has remained the gold-standard therapy, helping millions of patients regain movement and control. But as effective as levodopa is, it comes with a serious drawback in later stages of the disease — involuntary movements known as levodopa-induced dyskinesia (LID).

A new study from Northwestern Medicine offers an important shift in thinking. Instead of targeting dopamine levels alone, researchers suggest that aberrant learning signals in the brain’s striatum may be a key driver of these side effects. By interrupting this faulty learning process, scientists believe it may be possible to both enhance levodopa’s benefits and reduce its long-term complications.

Understanding Parkinson’s Disease and Its Progression

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that affects more than 8.5 million people worldwide, according to the World Health Organization. It primarily results from the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain, which normally help regulate movement, habit formation, and goal-directed behavior.

As dopamine levels decline, patients experience hallmark symptoms such as tremors, muscle rigidity, slowed movement, and impaired balance. In the early stages, medications are often highly effective. However, as the disease advances, treatment becomes increasingly complex, and side effects become harder to manage.

Why Levodopa Eventually Causes Problems

Levodopa works by converting into dopamine once it enters the brain, temporarily compensating for the neurons that have been lost. Early on, surviving neurons help regulate dopamine release smoothly. Over time, however, these neurons continue to die.

As a result, the brain loses its ability to buffer dopamine levels, leading to dramatic fluctuations. Dopamine concentrations swing between very high and very low, rather than remaining stable. These oscillations are believed to be a major contributor to levodopa-induced dyskinesia, a condition marked by uncontrolled and often disruptive movements.

Patients with advanced Parkinson’s are frequently forced to make difficult choices: lower their levodopa dose and accept worsening motor symptoms, or pursue deep-brain stimulation (DBS) — an invasive surgical procedure involving implanted electrodes.

A New Focus on Learning in the Striatum

The Northwestern Medicine study, led by D. James Surmeier, takes a different approach. Rather than viewing dyskinesia as a purely chemical side effect, the research suggests it is partly a problem of misguided learning.

The striatum, a deep brain region critical for movement and habit learning, relies on carefully timed signals involving dopamine and acetylcholine. These signals normally help the brain learn which movements are useful and which are not.

In Parkinson’s patients treated with levodopa, however, the medication appears to artificially recreate learning signals, regardless of actual movement or experience. Over time, this chemically driven learning becomes distorted — what the researchers describe as aberrant learning.

This faulty learning is thought to reinforce the neural patterns that cause dyskinesia, making involuntary movements more likely with continued levodopa use.

How the Study Was Conducted

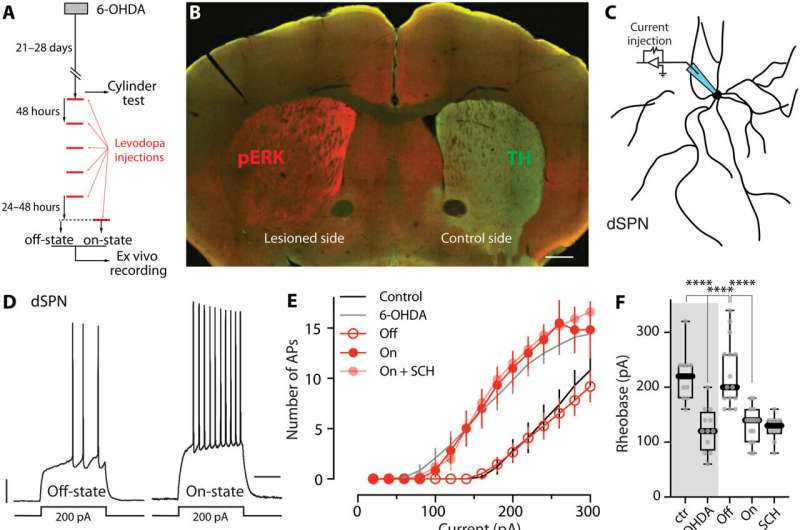

To investigate this idea, the research team used mouse models of Parkinson’s disease treated with levodopa. They focused on striatal spiny projection neurons (SPNs), the main neurons responsible for movement control within the striatum.

Using a combination of electrophysiology, pharmacology, molecular biology, and behavioral analysis, the scientists examined how these neurons changed between levodopa “off” and “on” states.

One key observation was that dopamine and acetylcholine levels in the striatum alternated abnormally, mimicking learning signals even when no real learning should be taking place. This alternating pattern closely resembled the conditions known to drive synaptic plasticity.

Disrupting Cholinergic Signaling to Protect the Brain

The researchers then tested whether interrupting this false learning could reduce dyskinesia. They targeted acetylcholine receptors on spiny projection neurons using both genetic and pharmacological methods.

By disrupting these receptors, they effectively blocked the learning mechanism without shutting down movement itself. The results were striking:

- Synaptic connectivity was preserved in key neuron populations

- Levodopa’s ability to stimulate movement improved

- The severity of dyskinesia was significantly reduced

In other words, levodopa worked better, while its most troublesome side effect was blunted.

Why This Matters for Parkinson’s Patients

This study suggests that dyskinesia is not just a consequence of too much dopamine, but also a result of how the brain learns under chronic medication exposure. That insight opens the door to a new class of therapies that could be used alongside levodopa rather than replacing it.

Importantly, targeting aberrant learning could reduce the need for deep-brain stimulation, which many patients are reluctant to undergo due to its surgical risks and costs.

The findings also highlight the importance of non-dopaminergic systems, particularly acetylcholine, in Parkinson’s disease — an area that has often been overlooked in favor of dopamine-centric treatments.

Broader Context: Dyskinesia and Current Treatment Limits

Levodopa-induced dyskinesia affects a large proportion of patients with long-standing Parkinson’s disease. Existing treatments, such as amantadine, offer partial relief but can introduce additional side effects. Surgical options like DBS are effective but not suitable for everyone.

Recent experimental drugs have attempted to target dopamine receptors more selectively, with mixed results. This new approach stands out because it aims to change how the brain adapts to treatment, rather than merely adjusting dopamine levels.

What This Could Mean for Future Therapies

The study points toward novel pharmacological and genetic strategies designed to interrupt maladaptive learning pathways in the striatum. Such therapies could potentially:

- Extend the effective lifespan of levodopa treatment

- Improve quality of life in late-stage Parkinson’s patients

- Delay or eliminate the need for invasive brain surgery

While the current findings are based on animal models, they provide a strong foundation for future clinical research.

Final Thoughts

Parkinson’s disease is often framed as a problem of missing dopamine, but this research adds a crucial layer to that understanding. By showing that aberrant learning mechanisms play a major role in levodopa-induced dyskinesia, scientists are reshaping how we think about treatment side effects.

If future therapies can successfully target these learning pathways, Parkinson’s patients may one day benefit from more effective and safer long-term treatments, without having to sacrifice mobility or undergo surgery.

Research paper:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adv8224