University of Mississippi Researchers Develop a New Zebrafish Model to Explore Autism Risk Factors

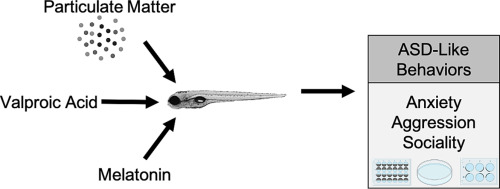

Researchers at the University of Mississippi have created a new scientific tool designed to help uncover how environmental factors and genetic influences may combine to affect the development of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Their work, led by assistant professor of environmental toxicology Courtney Roper and doctoral researcher Shayla Victoria, focuses on understanding how urban pollution, particularly airborne particulate matter, may shape brain and behavioral development. The study appears in Neurotoxicology and Teratology and aims to give scientists a reliable experimental system for analyzing ASD-related biological pathways.

This project addresses a long-standing challenge in autism research: the difficulty of separating environmental exposures from genetic predispositions in humans. Because ASD involves a complex interplay of genetics, environment, and neurodevelopment, human studies alone often cannot identify exact causative pathways. That is why scientists frequently turn to animal models, and in this case, Roper and Victoria selected zebrafish, a species that has become increasingly valuable in developmental neuroscience.

A Clear Look at Why Zebrafish Are Useful for Autism Research

The research uses developing zebrafish embryos because zebrafish offer several important advantages for studies of neurodevelopment:

- They have defined behaviors at very early stages.

- Their embryos grow externally, making developmental changes easy to observe.

- They can be produced in large numbers, enabling scalable experiments.

- Many zebrafish genes have human equivalents, supporting the study of genetic influences.

For ASD research in particular, zebrafish are useful because early behavioral responses are measurable within days, and scientists can monitor large populations under multiple exposure conditions. This helps researchers identify patterns or deviations in movement, response, and neural development.

Roper explained that the goal isn’t merely to study pollution as a standalone factor, but to create a model that allows scientists to place environmental exposures into a broader gene-environment framework. While the study did not detect ASD-like behavioral changes in every test involving particulate matter exposure, the model still showed measurable impacts on neural development and behavior—key indicators that the system works as a scientific tool.

Why Air Pollution Is Being Studied as a Potential Autism Risk Factor

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), roughly 1 in 31 children in the United States is diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Over the past decade, numerous epidemiological studies have hinted at a relationship between air pollution exposure, especially during pregnancy, and a heightened risk of ASD. Researchers have observed associations between in-utero exposure to particulate matter and later developmental diagnoses in children. However, proving causation in humans is extraordinarily complex.

The biological reasons behind the possible link revolve around how pollution can contribute to:

- Neuroinflammation

- Oxidative stress

- Immune system disruption

- Altered neuronal connectivity

- Epigenetic changes

All of these processes can affect early brain development. But human studies cannot ethically manipulate exposure, so researchers need other ways to study how pollutants interact with genetic susceptibilities. The zebrafish model gives them that opportunity.

Establishing an ASD-Like Benchmark Using Valproic Acid

To validate the model, the researchers turned to valproic acid, a medication widely used for epilepsy and bipolar disorder. This drug is known to significantly increase ASD risk when taken during pregnancy, and for that reason, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has warned against prescribing it to pregnant women.

In the study, valproic acid served as a benchmark. By exposing zebrafish embryos to the drug, Roper and Victoria created a baseline of autism-like behavioral changes. Then they compared those changes to the ones observed when the fish were exposed to particulate matter.

This approach allowed the researchers to determine whether pollution created behavioral patterns resembling those caused by a known ASD-linked risk factor.

What the Researchers Found

The particulate matter used in the study did alter the zebrafish’s neurological development and behavior. However, not all of these changes resembled ASD-like behaviors as defined by the valproic acid benchmark. This finding highlights a key nuance:

Environmental exposures can influence brain development, but not every type of pollutant or condition will mimic the behavioral patterns associated with ASD.

Still, the researchers emphasize that the model itself—not the specific outcome regarding particulate matter—is the major contribution of this work. The zebrafish system can be adapted to test other environmental contaminants, different exposure intensities, diverse developmental periods, and various combinations of genetic and environmental factors.

Why This Model Matters for Future Autism Research

This tool opens up a wide range of possibilities for future experiments:

- Testing different particulate matter types (such as PM2.5 vs. PM10).

- Studying longer developmental timelines, including impacts on adulthood.

- Analyzing how multiple contaminants might interact with each other.

- Observing how genetic variations modify outcomes under pollution exposure.

- Expanding behavioral testing to include new metrics relevant to ASD.

Roper noted that the model is not designed to prove or disprove whether a specific environmental factor causes autism in humans. Instead, it is meant to equip scientists with a controlled and repeatable system for investigating how environmental and genetic risks intersect.

The researchers aim to broaden the behavioral parameters observed in the fish and explore long-term developmental outcomes, not just early-stage responses. This will help build a more detailed picture of how exposure leads to changes in adulthood and whether those changes resemble known ASD characteristics.

Additional Context: Understanding Environmental Influences on Autism

Over the last two decades, research has increasingly focused on environmental contributors to autism alongside genetic factors. Scientists believe that ASD arises through a mix of influences, and certain environmental exposures may increase risk, particularly during sensitive windows such as:

- prenatal development

- early postnatal development

- early childhood

Some environmental factors that researchers continue to investigate include:

- airborne pollutants (particulate matter, nitrogen oxides)

- endocrine-disrupting chemicals

- pesticides

- heavy metals

- maternal health conditions during pregnancy

Identifying which exposures pose the highest risk can help guide public health measures, especially for vulnerable populations. Models like the one created by Roper and Victoria help advance this research by making it possible to test hypotheses that cannot be ethically investigated directly in humans.

The Bigger Picture: Why Tools Like This Are Valuable

The new zebrafish model adds to a growing toolkit that scientists use to study ASD. Because autism involves multiple layers of biology, researchers need systems that can isolate and test individual components—something nearly impossible in human populations.

Tools like this:

- enable high-throughput testing

- provide genetic control

- allow precise environmental manipulation

- support comparisons across exposures

- help generate hypotheses for future human studies

The University of Mississippi team stresses that their model is merely the starting point. As other researchers adopt and modify the system, the scientific community may gain a clearer understanding of how environmental factors affect brain development in ways that relate to autism.

Research Paper

Autism spectrum disorder-like behaviors in developing zebrafish exposed to particulate matter

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ntt.2025.107548