Why Anti-Estrogen Therapy Often Fails in Ovarian Cancer and How Scientists Are Finding a Way to Fix It

Anti-estrogen therapy has long seemed like a promising option for treating ovarian cancer, especially because a large number of tumors in the most common and aggressive subtype—high-grade serous ovarian cancer—carry estrogen receptors. Normally, that receptor presence is a green light for using hormone-blocking drugs. But despite those expectations, the real-world results have been disappointing. Many patients simply don’t respond, and until now, researchers couldn’t fully explain why.

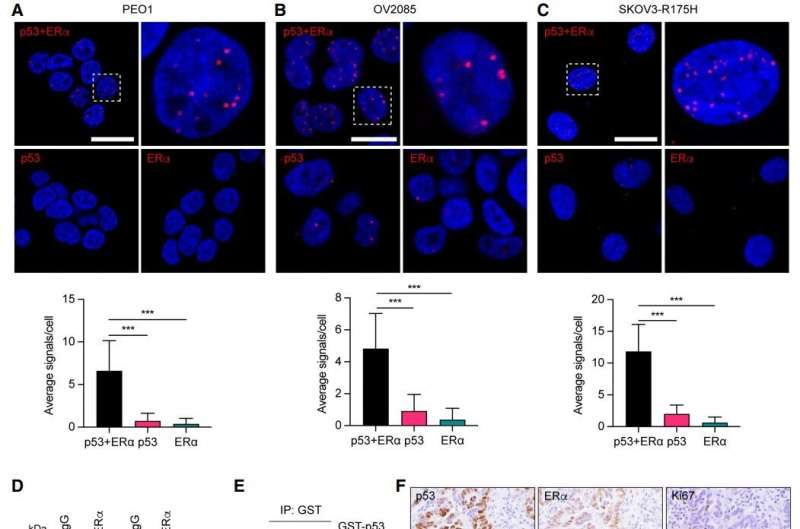

A newly published study from The Wistar Institute finally uncovers the mechanism behind this frustrating resistance. The research focuses on the mutant p53 protein, a genetic abnormality found in about 96% of high-grade serous ovarian cancers. According to the study, this mutated protein physically interacts with the estrogen receptor (ERα), preventing normal estrogen signaling inside the cell. Without that signaling pathway, anti-estrogen therapy loses its target, becoming far less effective than expected.

Below, I break down the study’s findings, the broader scientific context, and why this could reshape treatment approaches for ovarian cancer in the near future.

The Core Discovery: Mutant p53 Blocks Estrogen Signaling

The study, published in Genes & Development, reveals that mutant p53 binds directly to ERα, effectively choking off the pathway that would normally make a tumor responsive to hormone-blocking drugs. Even though around 70% of high-grade serous ovarian cancers express estrogen receptors, the presence of mutant p53 means that ERα isn’t functioning the way it should.

This explains why clinical trials of anti-estrogen therapies—drugs designed to interrupt estrogen’s cancer-promoting effects—have historically shown only about a 41% clinical benefit rate. On paper, these tumors should respond. In practice, they do not, because the signaling machinery is disrupted at the source.

The research team discovered this connection partly by investigating p53 variants more common in individuals of African descent. They noticed that people carrying certain variants had dampened activity in estrogen-responsive genes—an unexpected clue that eventually led them to test the interaction between mutated p53 and estrogen receptors in ovarian cancer cells.

Their experiments confirmed it: mutant p53 controls estrogen receptor activity, and that control leads directly to hormone-therapy resistance.

Reversing Resistance by Targeting Mutant p53

After discovering the role of mutant p53, the researchers tested whether turning off this mutated protein could restore the tumor’s sensitivity to hormone therapy. They used human ovarian cancer cells and patient tissue samples collected through collaboration with major cancer centers. When they silenced mutant p53, tumors that were once resistant became sensitive again.

They also confirmed that this resistance mechanism appears even in the earliest stages of ovarian cancer, suggesting that the mutation’s impact begins early in tumor development.

But the most exciting outcome came from testing a p53-targeting drug already being studied in clinical trials.

The Promise of Rezatapopt and Combination Therapy

One of the standout points in the study is the effectiveness of a compound called Rezatapopt, designed to target a specific p53 mutation known as Y220C. This mutation creates a pocket or structural instability in the protein, and Rezatapopt is engineered to fill that pocket and refold mutant p53 closer to its normal, functional shape.

When the researchers combined Rezatapopt + anti-estrogen therapy, tumors carrying the Y220C mutation became far more responsive. This indicates a clear therapeutic pathway for patients with that specific genetic profile.

Importantly:

- Rezatapopt is already in clinical trials, including at the University of Pennsylvania and other institutions.

- Because the drug is already being tested in humans, the combined therapy approach could reach patient trials relatively quickly.

- This approach represents a meaningful step toward precision medicine, where a patient’s exact mutation profile determines the optimal treatment strategy.

The research team plans to evaluate other p53 variants as well, with the goal of broadening the number of patients who could benefit from p53-targeted combination treatments.

Why This Study Matters for Ovarian Cancer Treatment

High-grade serous ovarian cancer is one of the most dangerous gynecological cancers. It has an 80% relapse rate after initial chemotherapy and is projected to cause 13,000 deaths per year in the United States. Given these numbers, improving available therapies is essential.

Anti-estrogen therapy seemed promising because the presence of estrogen receptors usually predicts sensitivity to hormone treatment—just like in many cases of breast cancer. But mutant p53 essentially rewrites that biology, blocking the intended pathway and leading scientists down a path of confusion for many years. This study finally explains the disconnect and offers a plan for overcoming it.

Because p53 mutations also occur in many breast cancers, these findings may help researchers understand why some breast cancer patients do not respond to endocrine therapy despite having estrogen-positive tumors.

Background: What Is p53 and Why Do Mutations Matter?

The p53 protein is often called the “guardian of the genome.” In its normal state, it prevents damaged cells from dividing, suppresses tumor growth, and triggers cell death when mutations occur.

But when p53 is mutated:

- It loses its tumor-suppressing function.

- It can acquire new, harmful abilities (called gain-of-function mutations).

- It interferes with other regulatory pathways, including hormone signaling, as shown in this study.

Because TP53 mutations are so common in high-grade serous ovarian cancer, targeting this mutation could influence outcomes for a huge percentage of patients.

Background: What Is Anti-Estrogen Therapy?

Anti-estrogen therapies work by:

- Blocking estrogen receptors

- Reducing estrogen levels in the body

- Preventing estrogen from signaling cancer cells to grow

These treatments are effective in many estrogen-driven cancers, especially ER-positive breast cancer. But in ovarian cancer, they have underperformed—largely due to the newly uncovered p53 mechanism.

Understanding the exact biological problem opens the door for more rational combination treatments.

What Happens Next in Research?

The research team is now:

- Testing other p53 mutations besides Y220C

- Developing diagnostic methods to identify which patients would benefit from p53-targeted treatment

- Working toward translating these findings into actionable clinical protocols for oncologists

Their long-term goal is to create a clinical tool that helps personalize treatment for ovarian cancer patients based on their tumor’s genetic makeup.

The Bottom Line

This study explains a long-standing mystery in ovarian cancer treatment: why anti-estrogen therapy so often fails despite the presence of estrogen receptors. The culprit—mutant p53 interfering with estrogen signaling—offers a clear reason for resistance and a promising pathway for restoring sensitivity using drugs like Rezatapopt.

If future clinical trials confirm the effectiveness of combining p53-targeting drugs with hormone therapy, this could open the door to improved outcomes for many patients battling one of the deadliest forms of ovarian cancer.

Research Paper:

Mutant p53 binds and controls estrogen receptor activity to drive endocrine resistance in ovarian cancer

https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.352953.125