Yale Scientists Identify a Key Molecular Difference in Autistic Brains That May Explain Signaling Imbalance

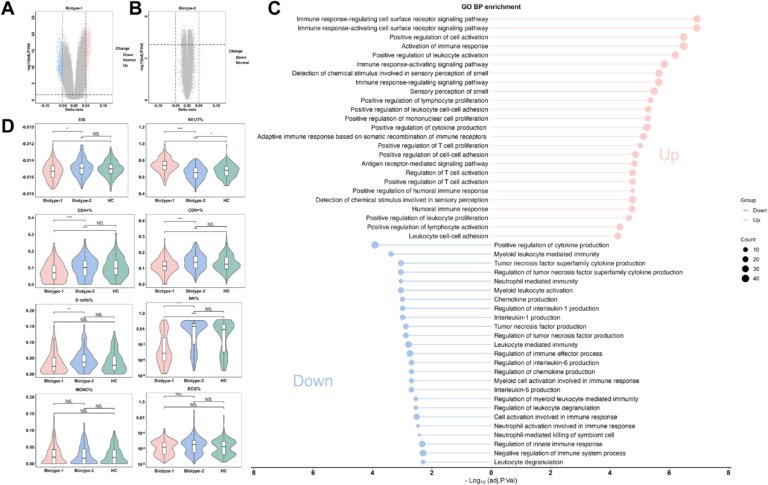

Scientists at Yale School of Medicine have uncovered an important molecular difference in the brains of autistic individuals that could help explain long-standing questions about how autism affects brain signaling. The study, published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, reports that autistic adults show reduced availability of a specific glutamate receptor, offering strong biological evidence for a theory that has guided autism research for decades.

Autism is a neurodevelopmental condition commonly associated with differences in social interaction, communication, sensory processing, and patterns of behavior such as repetitive movements or intense interests. While autism has been studied extensively at the behavioral and cognitive levels, the underlying biological mechanisms have remained difficult to pin down. This new research moves the field a step closer to understanding autism at a molecular and neurochemical level.

A Closer Look at Brain Signaling in Autism

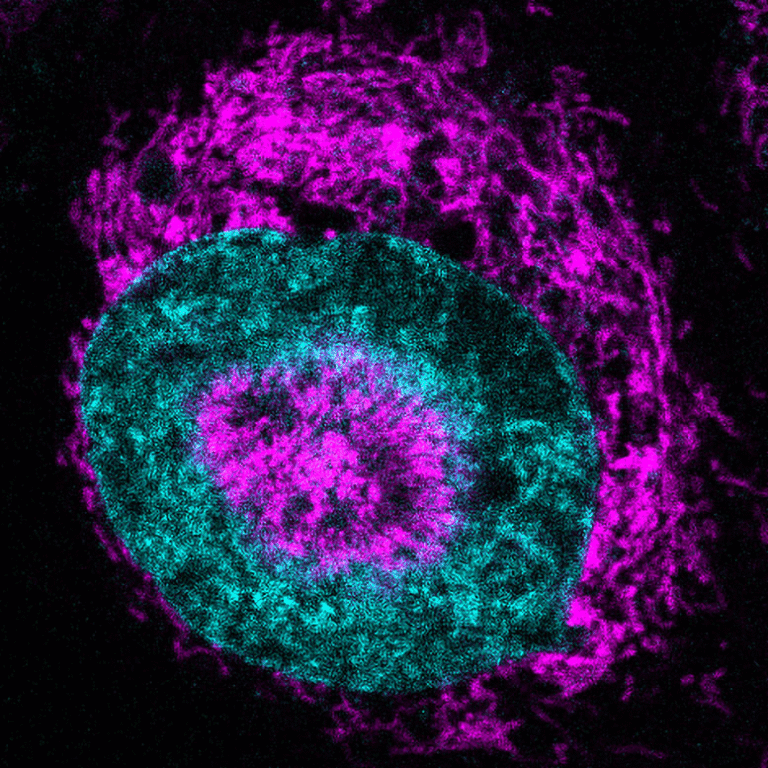

The human brain relies on a delicate balance of electrical and chemical signals to function properly. Neurons communicate through neurotransmitters, chemical messengers released when electrical signals travel through nerve cells.

There are two main types of signaling in the brain:

- Excitatory signaling, which increases the likelihood that neurons will fire

- Inhibitory signaling, which suppresses neural activity

The primary neurotransmitter responsible for excitatory signaling is glutamate, the most abundant excitatory chemical messenger in the brain. For years, researchers have proposed that autism may involve an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory signaling, sometimes referred to as an E/I imbalance. This imbalance has been suggested as a possible explanation for the wide range of neurological and behavioral differences seen across the autism spectrum.

Until now, however, direct evidence of this imbalance at the molecular level in living humans has been limited.

The Role of mGlu5 Receptors

The Yale study focused on a specific glutamate receptor known as metabotropic glutamate receptor 5, or mGlu5. This receptor plays a crucial role in regulating how neurons respond to glutamate and how excitatory signals are processed across brain networks.

Using advanced brain imaging techniques, the researchers compared 16 autistic adults with 16 neurotypical adults. All autistic participants had average or above-average cognitive abilities, which helped reduce variability related to intellectual disability.

Two main imaging methods were used:

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) to examine brain anatomy

- Positron Emission Tomography (PET) to measure receptor availability and molecular activity in the brain

PET scans allowed researchers to create a brain-wide molecular map of the glutamate system. What they found was striking: autistic participants showed reduced availability of mGlu5 receptors across large areas of the brain compared to neurotypical participants.

This reduction supports the idea that excitatory signaling in autism is altered in a measurable and biologically meaningful way.

Electrical Activity and EEG Findings

In addition to MRI and PET scans, 15 of the autistic participants also underwent electroencephalogram (EEG) testing. EEG measures electrical activity in the brain and is widely used because it is non-invasive, relatively inexpensive, and does not involve radiation.

The researchers discovered that specific EEG patterns were associated with lower mGlu5 receptor availability. This finding is particularly important because PET scans, while powerful, are costly and involve exposure to radiation, making them impractical for widespread clinical use.

EEG, on the other hand, could potentially serve as a more accessible tool for studying excitatory brain function related to glutamate signaling. While EEG cannot fully replace PET imaging, the study suggests it may help bridge the gap between molecular neuroscience and real-world clinical research.

Why This Discovery Matters

One of the most significant aspects of this study is that it identifies a measurable molecular difference in the living autistic brain. Currently, autism diagnoses rely almost entirely on behavioral observation and developmental history, not biological tests.

By identifying changes in mGlu5 receptor availability, researchers are beginning to outline what some scientists describe as a “molecular backbone” of autism. This does not mean autism can or should be reduced to a single biological marker, but it does provide a concrete biological reference point that could improve understanding, diagnosis, and support.

There are currently no medications that directly treat the core neurological differences associated with autism. While many autistic individuals do not need or want medical treatment, others experience challenges that significantly affect their quality of life. Understanding the role of mGlu5 receptors could help guide the development of targeted therapeutics aimed at glutamate signaling pathways.

Autism, Neurodiversity, and Clinical Balance

The researchers emphasize that autism exists within the broader framework of neurodiversity. Many autistic people lead fulfilling lives and do not view autism as something that needs to be “fixed.” At the same time, some individuals on the spectrum experience difficulties related to anxiety, sensory overload, or cognitive strain.

This research does not suggest a one-size-fits-all approach to autism treatment. Instead, it offers biological insight that may help support individuals who seek medical or therapeutic options tailored to their specific needs.

Limitations of the Current Study

While the findings are promising, there are important limitations to keep in mind.

First, the study included only adults. It is still unclear whether reduced mGlu5 receptor availability is a cause of autism or a long-term consequence of living with autism over decades. Historically, PET scans have not been used in children due to concerns about radiation exposure.

However, the research team has developed new low-radiation PET techniques, which may allow future studies involving children and adolescents. This could help researchers build a developmental timeline of how glutamate signaling changes over the lifespan in autism.

Second, all autistic participants had average or above-average intelligence. Future studies aim to include individuals with intellectual disabilities, using adapted imaging approaches to ensure broader representation across the autism spectrum.

What We Know About Glutamate and the Brain

Glutamate is essential for learning, memory, and neural plasticity. It plays a key role in how brain circuits develop and adapt over time. Disruptions in glutamate signaling have been linked not only to autism, but also to conditions such as schizophrenia, epilepsy, and depression.

The mGlu5 receptor is particularly interesting because it helps regulate both excitatory and inhibitory networks, acting as a kind of modulator rather than a simple on/off switch. Changes in its availability can have widespread effects on brain function, making it a compelling target for future research.

Looking Ahead

This study represents a meaningful step toward understanding autism beyond behavior alone. By identifying specific molecular differences in brain signaling, researchers are beginning to connect decades of theoretical work with measurable biological evidence.

Future research involving younger participants, larger sample sizes, and diverse cognitive profiles will be critical for determining how these findings fit into the broader picture of autism development. For now, the discovery of altered mGlu5 receptor availability offers a clear, testable biological insight into how autistic brains may process information differently.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.20241084