Zap-and-Freeze Technique Lets Scientists Watch Human Brain Cells Communicate in Real Time

Researchers at Johns Hopkins Medicine have successfully used a zap-and-freeze technique to observe some of the fastest and most elusive events in the human brain: the moment when neurons communicate through synapses. This achievement matters because it gives scientists a way to directly study how real human neurons send and recycle chemical messages, offering clues that could eventually clarify the biological roots of conditions like sporadic Parkinson’s disease.

The new findings, published on November 24 in Neuron, build on earlier work that tested zap-and-freeze in mice. This time, the team applied the method to living human cortical brain tissue, donated by six volunteers undergoing medically necessary epilepsy surgery at Johns Hopkins Hospital. Since these procedures involve removing small sections of brain tissue near the hippocampus, researchers were able to study freshly resected material with the patients’ permission.

Below is a clear breakdown of what the scientists did, what they discovered, and why these results matter for neuroscience and future clinical research. I will also expand the article with helpful background sections to strengthen understanding of synapses, vesicle recycling, and Parkinson’s disease.

How the Zap-and-Freeze Technique Works

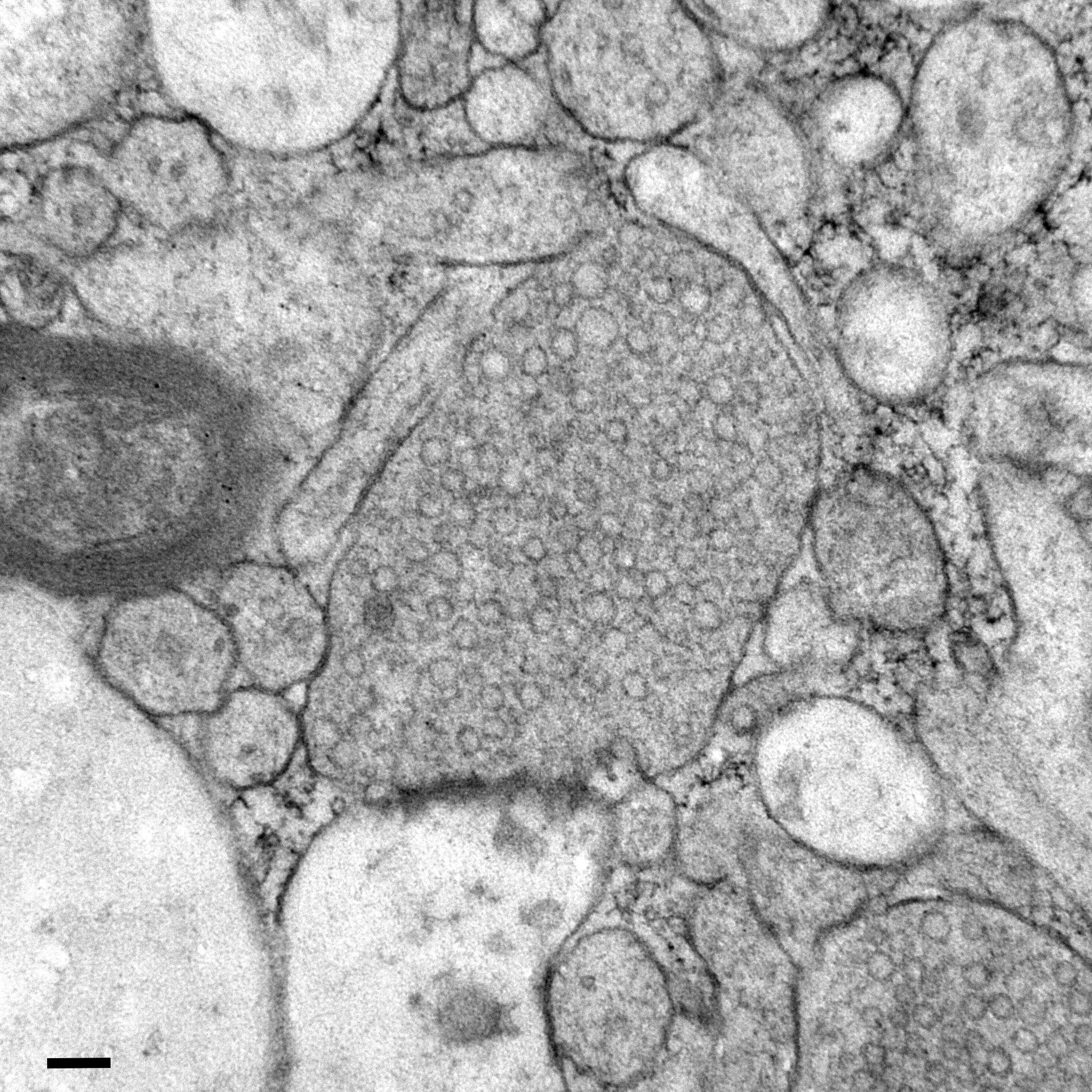

The zap-and-freeze method is designed to capture ultrafast synaptic events that ordinarily occur too quickly to photograph or analyze. In a living brain, chemical messages are passed from neuron to neuron at lightning speed. Traditional imaging techniques struggle to keep up with these movements, especially at the nanoscale.

Zap-and-freeze solves this by doing exactly what its name suggests:

- A tiny electrical pulse (the zap) stimulates neurons in the brain tissue.

- Almost immediately—within about 100 milliseconds—the tissue is rapidly frozen.

- The frozen samples are then examined with electron microscopy, which can visualize structures as small as synaptic vesicles.

This method essentially hits the pause button on molecular activity, allowing researchers to see where synaptic vesicles are located at precise points in time. These vesicles are tiny membrane-bound spheres that carry neurotransmitters, the chemicals used for communication between neurons.

The technique was originally developed several years ago to study synapses in mice, and the results published in 2020 validated its power for analyzing membrane dynamics. What’s new now is seeing that it works reliably in living human brain tissue, not just in animal models.

What the Scientists Observed in Mice

Before applying zap-and-freeze to human samples, the team first validated the technique once again in mice. Working with researchers Jens Eilers and Kristina Lippmann from Leipzig University in Germany, they used the method to observe:

- Calcium signaling, which triggers neurotransmitter release.

- Synaptic vesicle fusion, where vesicles merge with the neuron membrane to release neurotransmitters.

- Endocytosis, the recycling process that retrieves membrane material so the neuron can form new vesicles.

This recycling step is particularly important. Without it, neurons would quickly run out of vesicles and communication between brain cells would break down.

The mouse experiments also highlighted the presence of Dynamin1xA, a protein essential for ultrafast endocytosis—a specific, extremely rapid recycling pathway.

Once the method showed clear results in mouse brain slices, the researchers moved on to human tissue.

What They Discovered in Human Brain Samples

When the same approach was used on cortical tissue taken from epilepsy patients, the results were remarkably similar to what the team saw in mice.

Here are the key findings:

- Human neurons demonstrated the same vesicle fusion and release patterns.

- Vesicle recycling pathways mirrored those found in mice, including ultrafast endocytosis.

- Dynamin1xA appeared in the same membrane regions associated with recycling.

- The molecular machinery responsible for ultrafast vesicle recycling is strongly conserved between humans and mice.

This point is especially important because it validates decades of synapse research performed in animals. It suggests that the behavior of synaptic vesicles in mouse models is highly representative of human biology, at least at the structural and molecular level.

Why This Matters for Understanding Parkinson’s Disease

Most cases of Parkinson’s disease are sporadic, meaning they are not inherited. These cases do not stem from a single genetic mutation, so researchers have long searched for underlying cellular processes that might explain why neurons begin to malfunction.

One major hypothesis is that synaptic dysfunction contributes to the early stages of Parkinson’s. If vesicle recycling slows down or becomes disorganized, neurons may release neurotransmitters less effectively, which can disrupt circuits involved in movement.

Because zap-and-freeze allows scientists to visualize synaptic vesicle dynamics directly in human tissue, it could become a powerful tool for comparing:

- Healthy tissue

- Tissue from individuals with hereditary Parkinson’s

- Tissue from people with sporadic Parkinson’s

Johns Hopkins researcher Shigeki Watanabe, who led the study, has stated that the next step is to apply this technique to tissue from patients undergoing deep brain stimulation surgery for Parkinson’s disease. These surgeries occasionally produce small amounts of living brain tissue that could be studied with zap-and-freeze.

By comparing samples, scientists may pinpoint exactly how vesicle behavior differs in Parkinson’s patients— something that has never before been possible at this level of detail.

Understanding the Synapse: A Quick Background Section

To appreciate the significance of these findings, it helps to understand what a synapse is and why synaptic vesicles matter.

A synapse is the junction where one neuron communicates with another. It consists of:

- A presynaptic neuron, which releases neurotransmitters.

- A synaptic cleft, the tiny gap between cells.

- A postsynaptic neuron, which receives the message.

Inside the presynaptic neuron are synaptic vesicles filled with neurotransmitters such as dopamine, glutamate, or serotonin. When an electrical signal reaches the synapse, calcium floods in, triggering vesicle fusion at the membrane. The neurotransmitters spill into the cleft, bind to receptors on the next neuron, and transmit the message.

This all happens within milliseconds.

Once vesicles release their contents, the neuron must recycle the membrane rapidly. If this recycling slows down, synaptic communication weakens. That is why discovering a conserved mechanism for ultrafast endocytosis in humans is so important— it confirms that the brain relies on extremely fast recycling to function normally.

Why Vesicle Recycling Is a Big Deal in Neuroscience

Vesicle recycling is not a single process. Neurons use several pathways, including:

- Ultrafast endocytosis (a rapid process occurring within 100 milliseconds)

- Clathrin-mediated endocytosis (slower, occurring over seconds)

- Bulk endocytosis (used during intense activity)

Ultrafast endocytosis has been difficult to study because it happens so quickly and on such a small scale. Zap-and-freeze gives researchers a rare window into this microscopic world.

By confirming that ultrafast endocytosis exists in humans, the study strengthens the idea that any disorder affecting vesicle recycling— whether genetically inherited or sporadic—could lead to serious neurological symptoms.

The Path Forward

The zap-and-freeze technique is likely to be used in a growing number of neurological studies. Now that researchers know it works on human tissue, they can attempt to visualize:

- Synaptic differences in neurodegenerative diseases

- Drug effects on vesicle behavior

- How proteins such as intersectin or Dynamin1xA operate in diseased vs. healthy neurons

Each of these areas has the potential to reveal new therapeutic targets.

Research Reference

Ultrastructural membrane dynamics of mouse and human cortical synapses (Neuron, 2025)

https://www.cell.com/neuron/fulltext/S0896-6273%2825%2900837-2