How Did Husserl Confront Skepticism and Seek Certainty Through Phenomenological Method

Skepticism has always had this fascinating way of shaking us at the core. It whispers in our ear, “How do you really know anything for sure?” Think about it—what if all your experiences are just dreams, illusions, or tricks of the mind?

That kind of doubt isn’t just academic; it can feel deeply unsettling. But here’s where Edmund Husserl, the founder of phenomenology, steps into the story. Instead of running away from skepticism, Husserl takes it head-on. He thinks the key isn’t out there in the external world where things can deceive us but in here, within consciousness itself.

By focusing on what’s immediately given in experience, Husserl hopes to discover a kind of certainty that no skeptic can tear down. To me, that’s bold—it’s like saying, “Fine, doubt everything you want, but you can’t doubt the fact that doubting itself is happening in consciousness.”

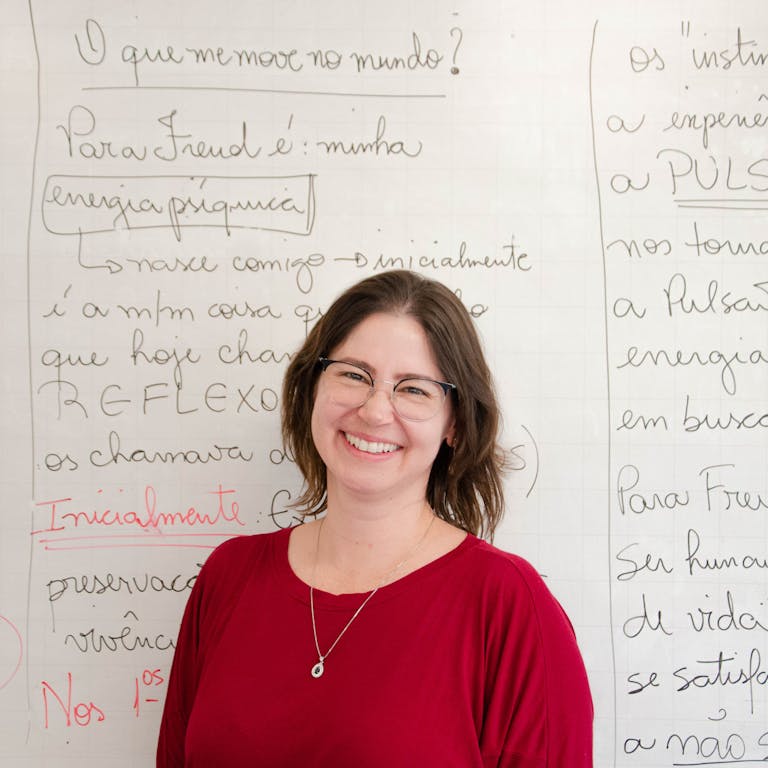

Husserl’s turn to consciousness

Here’s the big move Husserl makes: he argues that the best place to search for unshakable knowledge isn’t the world outside us, but our own conscious experience. That may sound obvious, but it’s actually pretty radical when you think about it.

Most of us assume that certainty, if it exists, must be about the world “out there.” For example, science tries to figure out whether particles, forces, or biological structures truly exist. But Husserl says: hang on, even before we can talk about atoms or galaxies, the one thing that’s impossible to deny is that we’re experiencing something right now.

Consciousness is always about something

Husserl uses a big word here: intentionality. Don’t let the term scare you—it just means that consciousness is always directed at something. If you’re thinking of an apple, your mind isn’t just floating in a vacuum; it’s oriented toward “apple-ness.”

If you’re worried about an exam, your thought isn’t just abstract—it’s pointed at that upcoming test. This “aboutness” is what gives consciousness its structure.

Here’s why that’s clever: even if the apple turns out to be fake, even if the exam gets canceled, the experience of “thinking about the apple” or “worrying about the exam” is absolutely real.

Skepticism might undermine the external object, but it can’t erase the fact that there was an act of consciousness.

The trick of bracketing

Now, you might ask, how do we deal with all the messy doubts about whether things exist? Husserl introduces a method he calls bracketing (or epoché if you want the Greek).

Imagine putting everything you believe about the world into mental parentheses. You don’t deny the world exists, but you also don’t lean on it. Instead, you focus only on what’s left—the pure act of experiencing.

For instance, when you look at a tree, you normally just assume, “Yeah, there’s a tree outside my window.” Husserl says: hold that assumption in brackets for a moment.

What you know for certain is the appearance of the tree in your consciousness. The colors, the shapes, the way the light filters through the leaves—those are undeniable. Whether the tree exists outside of you is another question, but the lived experience of “tree-seeing” is rock-solid.

This shift is powerful because it sidesteps the skeptic’s challenge. The skeptic might say, “But what if the tree doesn’t exist?” Husserl replies, “That’s fine—what matters is that I have the experience of it, and that’s indubitable.”

Consciousness as the new foundation

Think of it like this: Descartes famously tried to ground certainty in the statement “I think, therefore I am.” Husserl pushes this further. It’s not just that I exist because I think, but that the structures of consciousness themselves can provide the foundation for all knowledge. By carefully analyzing how experiences appear, we can uncover truths that don’t depend on whether the external world tricks us.

A simple example: imagine hearing a melody. You don’t just hear isolated notes; your consciousness strings them together into a flowing pattern. That structure isn’t an illusion—it’s how experience works. Even if the music is just playing in your head, the way consciousness organizes sound into meaning is real and can be studied.

Why this matters today

This might feel a bit abstract, but it has real bite. Think about virtual reality. When you put on a VR headset, the objects around you aren’t “real” in the physical sense. Yet, the experiences—the way you dodge a digital ball or reach for a glowing object—are entirely real in consciousness. Husserl gives us the tools to analyze that without worrying about whether the object is materially present.

Or take anxiety. If I’m anxious about losing my job, that anxiety shapes how I see the world: every email feels like bad news, every pause in conversation feels like judgment. The job loss might not even be real, but the experience of anxiety is certain and can be explored to understand how it structures perception.

Husserl’s turn to consciousness is a brilliant move because it flips the skeptic’s weapon. Instead of saying, “What if nothing’s real?” he says, “That’s fine—we’ll build knowledge from the one thing you can’t deny: the fact that experiences are happening.” That shift creates a whole new way of doing philosophy, one that doesn’t collapse under the weight of doubt. And honestly, I find that both humbling and exciting—it’s like he found a secret door out of skepticism’s maze.

Husserl’s tools for finding certainty

Alright, so we’ve got the basic setup: Husserl wants to resist skepticism by grounding knowledge in consciousness itself. But how does he actually do that? This is where his method comes in, and I’ve gotta say, it’s pretty ingenious. Husserl doesn’t just throw around abstract claims—he develops a toolkit that lets us carefully examine experience and pull out what’s certain. Let’s break down the major tools he uses.

Phenomenological reduction (the famous “bracketing”)

We touched on this earlier, but it’s worth slowing down. The phenomenological reduction is Husserl’s way of saying, “let’s suspend judgment about whether the external world exists and focus only on the experience itself.”

Think of it like switching from “regular vision” to “x-ray vision.” Normally, when you see a coffee cup, you instantly think, “That’s a cup on my desk.” But with phenomenological reduction, you pause that assumption. Instead, you pay attention to the appearance of the cup—the round shape, the warm color, the way your hand reaches for it.

Why does this matter? Because by bracketing the existence of the world, you free yourself from the skeptic’s trap. If someone says, “What if the cup is an illusion?” you can shrug and reply, “Doesn’t matter—I’m studying the experience itself, and that’s undeniable.”

Here’s an everyday analogy: when you watch a movie, you don’t question whether the characters are “real.” You focus on what’s happening on the screen—the images, the emotions, the story. Husserl wants us to treat consciousness the same way: analyze the presentation, not the “behind-the-scenes.”

The transcendental ego

Okay, this one sounds spooky, but stay with me. Husserl argues that underneath all our experiences, there’s a stable point of reference: the transcendental ego. This isn’t your personality, your quirks, or your memories. It’s the pure “I” that experiences.

Imagine playing different roles in life: student, friend, employee, gamer, whatever. All those roles shift, but the fact that “you” are the one experiencing them doesn’t change. That’s the transcendental ego—the witnessing subject.

Skeptics might try to pull the rug out from under you, but they can’t deny that there’s always an “I” to whom experiences appear. Without that center, doubt itself couldn’t exist. So Husserl says, let’s use this as our rock-bottom certainty.

Intentional acts

Here’s where Husserl’s earlier idea of intentionality gets really practical. He says we shouldn’t just study experiences as blobs of feeling. Instead, we should study them as acts of consciousness directed at objects.

Take memory. When I remember my high school graduation, my consciousness is actively pointing toward that event, even though it’s in the past. Or take imagination: when I picture a unicorn, my consciousness is directed toward something that doesn’t exist in the physical world. The key is that these acts have structure: they’re not random, they’re organized ways of relating to objects.

By analyzing these acts—perception, memory, imagination, judgment—we can uncover stable truths about how consciousness works. And again, this doesn’t depend on whether the objects are “real.” The unicorn may not exist, but the act of imagining it is absolutely real and analyzable.

Essence and eidetic reduction

This part is kind of like Husserl’s secret weapon. Once we bracket the world and study intentional acts, we can start looking for essences. These are the universal structures that show up across experiences.

For example, think about chairs. You’ve sat on wooden chairs, plastic chairs, beanbags, maybe even a funky chair made of metal wires. They’re all different, but through reflection, you can notice the essence of “chairness”—something to sit on, structured for support, connected to the body in a particular way.

Husserl calls the method for finding these essences eidetic reduction. You strip away the accidental details (color, size, material) and uncover the core structure of the experience. In the case of consciousness, you’re not just finding the essence of “chair,” but the essence of “perceiving a chair,” or “imagining a chair,” or “judging a chair’s usefulness.”

This is Husserl’s way of building a science of consciousness that’s as rigorous as physics or biology. Instead of relying on experiments in a lab, you experiment in thought by reflecting on experience itself.

Why this toolkit matters

Here’s the big payoff: by using reduction, the transcendental ego, intentional acts, and essences, Husserl claims we can secure a foundation of knowledge immune to skepticism. Even if the entire external world were a hallucination, the structures of consciousness—the way things appear, the ways we intend objects, the essences of experience—remain solid.

It’s a bold claim, but think about it: so much of modern life—VR, digital media, even therapy—already relies on analyzing experience as experience. Husserl just gave us the philosophical blueprint for why that works.

How Husserl answers the skeptic

Now we get to the juicy part—how all these ideas actually go toe-to-toe with skepticism. Skeptics love to unsettle us with questions like: What if you’re dreaming? What if the world doesn’t exist? What if your senses always deceive you? Husserl doesn’t deny these possibilities. Instead, he flips the script and shows why they don’t undermine certainty at the level of consciousness.

Turning skepticism on its head

Let’s start with the dream argument. Suppose you’re dreaming right now. A skeptic might say, “See? You can’t be sure the world is real.” Husserl would respond, “True, but what I can be sure of is that I’m having the experience of dreaming. And that experience has a structure I can study.”

This is the crucial move: instead of trying to disprove skepticism, Husserl dissolves it by shifting the ground. You can doubt the world, but you can’t doubt the act of doubting itself. Consciousness remains.

Consciousness as indubitable evidence

Think of when you feel pain. You might question whether the cause of the pain is real—maybe it’s phantom limb pain, maybe it’s psychosomatic. But the pain as experienced is certain. Husserl generalizes this: every act of consciousness, whether perception, imagination, or judgment, provides indubitable evidence of itself.

And here’s the kicker: this doesn’t mean we retreat into solipsism (the idea that only your mind exists). Husserl insists that the very structure of consciousness points us outward. For instance, when I see a chair, I don’t just see isolated colors and shapes; I see it as a chair in the world. The experience itself points to a world beyond me, even if I bracket its actual existence.

Dissolving doubt with structure

What makes Husserl powerful is his focus on structure. The skeptic says, “How do you know the world exists?” Husserl replies, “Maybe I don’t—but what I do know is the way experiences are structured.”

Take time-consciousness. When you listen to a song, you’re aware of the note you just heard, the note you’re hearing now, and the anticipation of the next one. That temporal structure is certain—it’s how consciousness works, regardless of whether the song exists “out there.”

This means skepticism loses its sting. Even if the world were fake, the structures of experience—time, intentionality, essence—would still be knowable.

Modern echoes of Husserl’s solution

I find this incredibly relevant today. Think about AI-generated content. You might wonder: is what I’m seeing “real” or just computer-simulated? Husserl would say, that question is secondary. What’s certain is the experience you’re having—the text, the visuals, the meaning they carry for you.

Or take therapy. When someone describes trauma, the skeptic could ask, “Did the event really happen as they remember?” But from Husserl’s perspective, the memory itself—its vividness, its emotional tone—is real in consciousness, and analyzing it gives genuine knowledge.

Husserl’s method doesn’t eliminate skepticism by force; it makes it irrelevant. Skeptical doubts can’t touch the one thing they depend on: the fact that consciousness is happening, here and now, with a structure that can be studied.

Why this matters for us

For me, the beauty of Husserl’s approach is that it doesn’t chase after certainty in the external world, which is always vulnerable to doubt. Instead, it grounds certainty in something closer, something no one can strip away: the lived texture of experience.

It’s kind of comforting, honestly. In a world where misinformation, illusions, and uncertainty abound, Husserl reminds us there’s always one anchor we can hold onto: the undeniable reality of our own experiencing. That might not solve every philosophical puzzle, but it gives us a place to stand when everything else feels shaky.

Final Thoughts

Husserl’s project isn’t easy—it takes patience to slow down and examine experience without jumping to assumptions. But his genius was realizing that certainty doesn’t have to be about the external world. It can be about the way things show up in consciousness. By turning inward, Husserl found a foundation that skepticism can’t shake.

And honestly, that’s a lesson worth carrying beyond philosophy. Whether we’re questioning the reality of a virtual world, the accuracy of our memories, or the trustworthiness of what we see online, Husserl gives us a gentle reminder: even if you doubt everything else, you can never doubt the fact that you’re experiencing something right now. And that’s where knowledge begins.