Theory of Living Well in a World Without Absolute Moral Rules or Fixed Foundations

We usually grow up believing there must be some solid ground under our feet when it comes to right and wrong. We want absolutes—clear lines, universal rules, something we can lean on.

But what happens when that ground vanishes? Continental philosophers have spent the last century asking this very question, and honestly, their answers are both unsettling and liberating. Instead of chasing perfect truths, they ask us to look at how we actually live, how we meet other people, and how we make choices when no cosmic referee is keeping score.

To me, this way of thinking isn’t about moral chaos—it’s about embracing the messiness of being human. If you’ve ever felt overwhelmed by the gray areas of life, this conversation might not only feel familiar, it might also give you a new way to carry responsibility without waiting for absolutes to tell you what to do.

Living Without Solid Ground

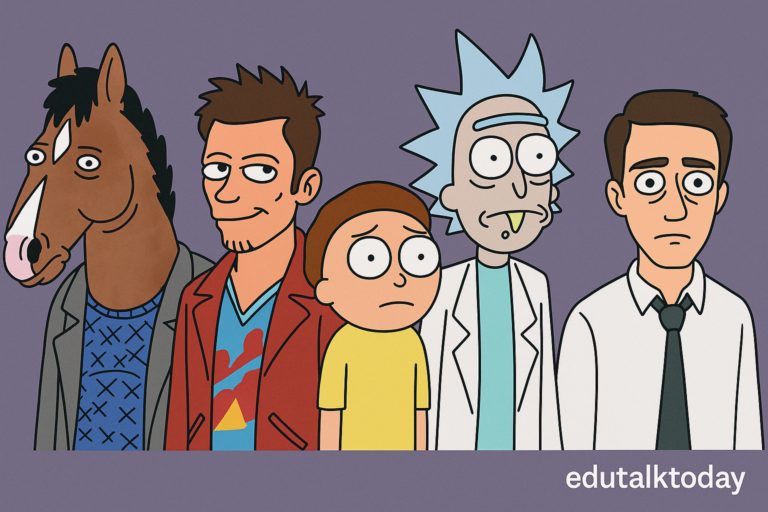

Nietzsche and the collapse of certainty

Friedrich Nietzsche is often the first name that pops up when people talk about the absence of absolutes. His famous line about the “death of God” wasn’t him cheering for atheism—it was him noticing that the cultural authority of religion had eroded. The shared anchor of morality that had guided societies for centuries was slipping away. Now, imagine being in a boat and realizing the shoreline you’ve always navigated by has disappeared. That’s what Nietzsche thought modern humans were experiencing. And here’s the twist: instead of mourning it, he saw it as a chance to create new values.

Nietzsche gives us the figure of the Übermensch—not a comic-book superhero but a person bold enough to craft meaning in a world without a built-in script. If you’ve ever had to reinvent yourself after a breakup, job loss, or some other life shake-up, you’ve felt a taste of this. There’s no absolute rulebook, so you’re left with the frightening but exhilarating task of writing your own.

Sartre and the weight of freedom

Jump ahead a few decades and you find Jean-Paul Sartre saying something equally radical: we are “condemned to be free.” That phrase always makes me smile a bit because it captures how freedom can feel both empowering and crushing. According to Sartre, since there’s no divine blueprint for our lives, every choice we make defines us. There’s no one else to blame, no cosmic excuse.

Let’s take a simple example: say you decide to skip voting because “my one vote doesn’t matter.” Sartre would argue that you’ve made a choice that reflects your values, and you can’t hide behind indifference. Your freedom is inescapable. To me, that’s a little terrifying—because it means every shrug, every “whatever,” is also a form of responsibility. But it’s also oddly hopeful, because it means our lives aren’t locked down by absolutes. They’re open, and we’re the authors.

Levinas and the face of the other

But continental philosophy isn’t all about the lone individual making heroic choices. Emmanuel Levinas flips the script by focusing on our responsibility to others. He talks about the ethical demand that shows up when you encounter another person face to face. And here’s what’s fascinating: this obligation doesn’t come from laws or rules—it comes from the vulnerability of the other person themselves.

Think of walking down the street and someone drops their bag. You don’t need a law book to know you should help. In that moment, their need calls out to you. For Levinas, this is where ethics starts: in the infinite responsibility we feel in the presence of another human being. What I love about his approach is that it makes morality less about abstract debates and more about actual human encounters.

Derrida and the impossibility of perfect justice

Then there’s Jacques Derrida, who takes the conversation even deeper—and honestly, trickier. He argues that every attempt to apply justice through laws will always fall short, because laws are rigid, but life is messy. True justice is always just out of reach, and yet we’re still responsible to keep striving for it.

Here’s an example: think about immigration policies. Laws set categories, quotas, and procedures. But then you meet a real person whose life doesn’t fit neatly into those boxes. Derrida would say justice isn’t about simply applying the rule—it’s about staying open to that unique person’s situation, even when the law can’t capture it. That tension—between law and justice, between rules and responsibility—isn’t a flaw. It’s the heart of ethics in a world without absolutes.

Why this matters for us

What ties all these thinkers together is the idea that living without absolutes doesn’t mean living without ethics. On the contrary, it raises the stakes. Without a fixed system, responsibility becomes more personal, more immediate, and sometimes more uncomfortable. Nietzsche pushes us to create meaning, Sartre reminds us that every choice counts, Levinas shows us the power of face-to-face responsibility, and Derrida keeps us humble about the limits of our systems.

If you ask me, that’s a lot more demanding than just following commandments. It’s also more alive. Ethics becomes something we’re constantly negotiating, not something handed down once and for all. And isn’t that closer to how we actually live? Every day, we’re navigating shifting contexts, unexpected encounters, and messy realities. These philosophers don’t give us neat answers—but they do give us courage to face the uncertainty with responsibility rather than despair.

Key Lessons for Living Without Absolutes

When I first started reading these continental thinkers, I thought, “Okay, if there are no absolutes, doesn’t that mean anything goes?” But the more I sat with it, the more I realized it’s actually the opposite. When there’s no cosmic referee calling the shots, the weight of living ethically lands right in our laps. And that’s where things get interesting. Let me break down a few key insights that come out of this way of looking at the world.

Freedom is responsibility

Here’s the thing: freedom isn’t just about doing whatever you want. If you’ve ever moved out on your own for the first time, you know what I mean. You suddenly realize no one’s forcing you to do laundry, but if you don’t, your room smells like a gym locker. That’s Sartre in everyday life. When there’s no absolute authority dictating the rules, every act of freedom comes bundled with responsibility. You’re free, but you’re also accountable for what that freedom creates.

The call of the other

Levinas’s idea of the face of the Other really gets under my skin—in a good way. It’s so simple: when you see another person, their very presence calls you to act responsibly. Think about someone looking at you with eyes full of trust, or fear, or hope. That’s not a situation you can just “opt out” of. Levinas would say that ethics begins in those fragile, messy encounters. Honestly, I think this resonates with our everyday life more than any moral code.

Ambiguity is essential

I used to think that the problem with ambiguity was that it made decision-making harder. But continental philosophy flips that: ambiguity is what makes ethics possible. If everything were black and white, there’d be no need for responsibility—you’d just follow the script. But life isn’t a multiple-choice test. It’s more like an open-ended essay. Ambiguity forces us to engage, wrestle, and decide, even when there’s no guarantee we’re right.

Justice goes beyond the rules

Derrida’s point about law and justice might feel abstract at first, but it’s deeply practical. Rules are necessary—otherwise, society collapses. But the rules never capture the whole story. Think about “zero tolerance” policies in schools. They sound neat and fair on paper, but in reality, they can punish kids who don’t deserve it. Derrida would remind us that justice requires us to look beyond the rigidity of rules and stay attentive to the unique circumstances of each situation.

Ethics as becoming

This one is my favorite takeaway: ethics isn’t about being something fixed—it’s about becoming. Nietzsche’s vision of creating new values, or Sartre’s idea of defining ourselves through choices, both point to the same thing: morality isn’t a static checklist. It’s a living, ongoing process of shaping who we are. That means we’re never done, and that’s actually good news. It keeps us humble, flexible, and always in motion.

Why these lessons matter today

All of these ideas might sound a little lofty, but they’ve shaped how I see real-world challenges. Take climate change. There’s no absolute playbook for how to handle it—just competing narratives, conflicting interests, and a lot of uncertainty. But that doesn’t mean we throw up our hands. It means we embrace the ambiguity, recognize our responsibility, and act anyway. Same with technology: AI, social media, and digital privacy are full of gray zones. But instead of waiting for perfect absolutes to appear, we lean into the responsibility of navigating complexity.

What I love about these continental insights is that they’re not just intellectual exercises. They’re reminders that living ethically isn’t about following a neat set of rules. It’s about stepping into freedom, listening to others, embracing ambiguity, questioning rigid systems, and staying open to becoming. It’s messy, sure—but it’s also what makes life human.

Living Responsibly in a World Without Certainty

So how do we take all of this high-level philosophy and actually use it in everyday life? That’s the question that makes the whole thing worth exploring. Because if we can’t apply these ideas to our messy, complicated world, then what’s the point?

Responsibility in personal choices

Start small: think about your own daily decisions. From what you eat, to how you spend money, to how you treat people at work—these choices don’t come with cosmic instructions. But they do matter. Sartre would say every one of them reflects your freedom. Levinas would nudge you to notice the people impacted by those choices. And Nietzsche might encourage you to use them to build a life that feels authentic, not just conventional.

For example, say you’re at the grocery store and tempted by the cheap fast-fashion-style shirt they just stocked. You know it’ll fall apart in a month, and you’ve read about sweatshop labor behind those products. No absolute rule is telling you what to do here. But the decision you make carries weight—on the planet, on workers, on your own sense of integrity. That’s ethics in action, without absolutes.

Responsibility in politics and society

Zoom out, and the stakes get even higher. Politics is a perfect example of what Derrida was talking about: laws versus justice. Policies are necessary, but they never capture the full complexity of human life. When we argue about immigration, healthcare, or policing, the real challenge is balancing the structure of laws with the demand for justice in concrete lives.

And here’s where continental philosophy keeps us grounded: it tells us not to wait for a perfect formula. There won’t be one. Instead, it’s about staying open, listening carefully, and refusing to let rigid rules blind us to lived realities.

Responsibility in the digital world

Let’s be real: the internet has made life more ethically complex than ever. Who owns your data? Should companies moderate speech? What’s fair when AI systems make decisions that affect people’s lives? These aren’t yes-or-no questions with neat answers. They’re ambiguous, and that ambiguity is the playground of continental ethics.

If we accept Levinas’s point, we’d say: focus on the people behind the data, behind the screens, behind the algorithms. If we take Derrida seriously, we’d recognize that laws about technology will always lag behind the actual issues, so we need constant vigilance. If we channel Nietzsche, we might even ask how we can use this freedom to create better ways of living with technology, not just passively consume it.

Why responsibility feels heavier but also richer

I’ll admit: living without absolutes is exhausting sometimes. It means you can’t just lean back on “that’s the rule” or “that’s tradition.” But it also feels richer, more alive. It treats us like grown-ups in the best sense: people capable of wrestling with uncertainty and still choosing to act.

Think about the last time you had to make a really tough decision—maybe about ending a relationship, moving cities, or changing careers. Chances are, there wasn’t one clear right answer. But in making that decision, you defined something about yourself. That’s exactly what these philosophers are talking about: responsibility as a way of becoming, even when certainty isn’t available.

A different kind of hope

What gives me hope in all of this is that it shifts the focus away from chasing absolutes and toward cultivating responsibility. It doesn’t mean everything is relative or meaningless—it means meaning is something we actively build, together. It’s humbler than grand universal systems, but also more adaptable. And in a world that’s constantly changing—climate, technology, politics—that adaptability might be the most ethical stance we can take.

Final Thoughts

Living without absolutes isn’t about chaos—it’s about courage. The courage to face freedom, to recognize the call of others, to navigate ambiguity, and to push laws toward justice even when they fall short. Nietzsche, Sartre, Levinas, and Derrida don’t hand us a ready-made map. They give us something better: the tools to walk responsibly without one. And maybe that’s the most human way to live—uncertain, imperfect, but always responsible.