A New Acoustic Wave Sensor Can Detect Proteins and Single Cancer Cells Without Shrinking the Device

At the center of every imaging system, whether it’s a smartphone camera or a high-end scientific microscope, sits a sensor. Traditionally, when scientists want to observe smaller and smaller objects, they are forced to make those sensors smaller too. That approach works only up to a point. Once sensors shrink beyond a certain limit, their performance, sensitivity, and reliability drop sharply. A new breakthrough from researchers at Northeastern University offers a way around that long-standing problem.

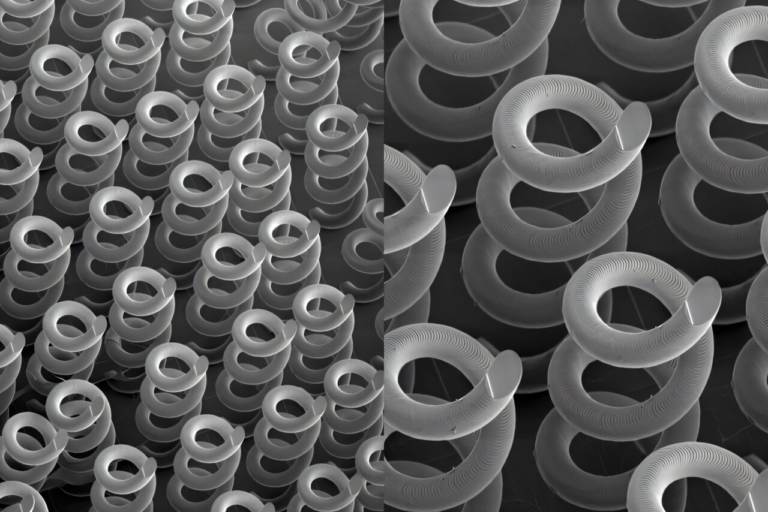

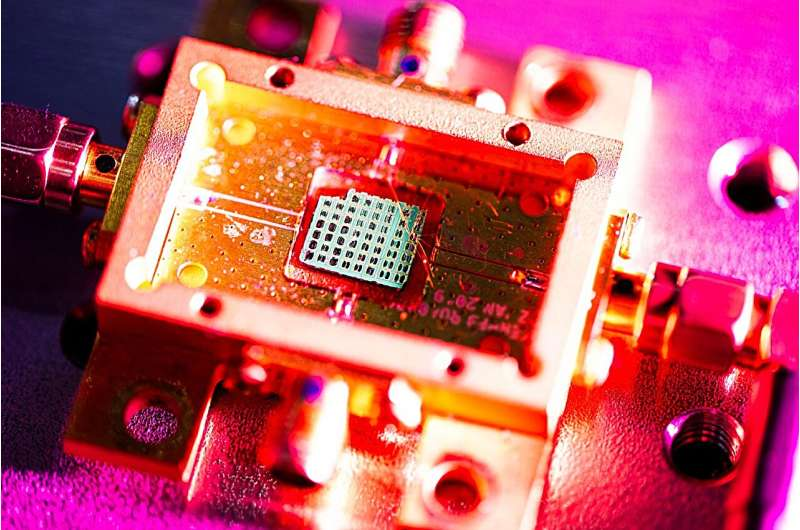

The research team has developed a topological guided acoustic wave sensor that can detect objects as tiny as individual proteins or single cancer cells, without needing to miniaturize the sensor itself. Instead of relying on light, this device uses acoustic waves and a special class of physical states known as topological interface states to achieve extraordinary precision at extremely small scales.

The result is a sensor roughly the size of a belt buckle that opens new doors in fields ranging from precision medicine to quantum computing.

Why Shrinking Sensors Has Been a Problem

In conventional imaging and sensing technologies, higher resolution usually means smaller components. When engineers reduce the size of pixels or sensing elements, they inevitably run into physical limits. According to the researchers, as sensors become smaller, they suffer from higher noise levels, lower sensitivity, and degraded performance.

Cristian Cassella, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at Northeastern University and a specialist in microelectromechanical systems (MEMS), has spent years working with devices that operate at scales smaller than the width of a human hair. His central question was deceptively simple: how can you get the effect of smaller sensing elements without actually shrinking them?

This challenge pushed the team to explore unconventional physics rather than traditional engineering trade-offs.

The Physics Behind the Breakthrough

The solution emerged from a collaboration between Cassella and his colleagues Marco Colangelo and Siddhartha Ghosh, both assistant professors of electrical and computer engineering at Northeastern. Colangelo, in particular, is an expert in condensed matter physics, which studies how matter behaves at atomic and sub-atomic scales.

The key concept behind the new sensor is the use of topological interface states. In condensed matter physics, topological states are special configurations of matter that allow energy to move in highly controlled ways. What makes them especially powerful is their ability to confine energy into extremely small, localized regions without being disrupted by imperfections or external noise.

In this sensor, guided acoustic waves are channeled along these topological interfaces. Instead of spreading across the entire device, the energy becomes sharply focused into nano-scale regions, allowing the sensor to respond to very small and localized changes.

To put that into perspective, one nanometer is one-billionth of a meter. Operating reliably at that scale is something conventional sensors struggle to do.

How the Acoustic Wave Sensor Works

Unlike optical sensors that rely on light, this new device uses acoustic waves, essentially vibrations traveling through solid materials. These waves are guided and confined using carefully engineered structures that support topological states.

The researchers demonstrated the concept with a proof-of-principle experiment. They used the sensor to detect a low-power infrared laser beam with a diameter of just five micrometers, roughly one-tenth the width of a human hair. Despite the laser’s small size and low power, the sensor could clearly and reliably detect it.

What makes this particularly impressive is that the sensor did not require extreme miniaturization to achieve this level of precision. Instead, it relied on clever physics to bypass the usual limitations associated with shrinking devices.

Why This Matters for Medicine and Biology

One of the most exciting aspects of this technology is its potential impact on biological and medical sensing. Detecting individual proteins or single cancer cells is a long-standing goal in biomedical research and diagnostics. Early detection at this level could dramatically improve outcomes in diseases like cancer, where identifying problems sooner often leads to better treatment options.

Because the sensor can focus energy into extremely small regions, it could be used to monitor minute biological interactions, such as changes in mass, mechanical properties, or energy absorption at the cellular or molecular level. This level of sensitivity is difficult to achieve with current MEMS-based biosensors.

Importantly, the sensor’s relatively large physical size compared to nano-devices makes it easier to manufacture, integrate, and deploy in real-world systems.

Implications for Quantum and Nano-Scale Technologies

Beyond medicine, the research has significant implications for quantum computing and nano-scale physics. Quantum systems are notoriously sensitive to noise and external disturbances. The ability to localize and control energy with such precision could help researchers build better tools for probing quantum states and interactions.

Colangelo has pointed out that the device also opens new avenues for fundamental physics research. Some of the underlying mechanisms governing how these topological acoustic states behave are not yet fully understood. Studying them in practical devices could lead to new discoveries that go beyond sensing alone.

Avoiding the Usual Scaling Limits

Siddhartha Ghosh emphasized that the biggest advantage of this approach is how it avoids the traditional scaling problem. Instead of making devices smaller and smaller, the researchers used advanced physical principles to achieve equivalent or better performance at the same size.

This shift in thinking could influence how engineers design future sensors, moving away from pure miniaturization and toward physics-driven performance enhancement.

A Platform for the Next Decade of Research

While the initial results are promising, the researchers are careful not to overstate the immediate impact. This work represents a proof of concept, not a finished commercial product. That said, Cassella has expressed confidence that this technology will remain a focus of research for many years to come, potentially the next decade.

The project itself was made possible through collaborative funding and shared laboratory resources at Northeastern’s EXP building, highlighting the importance of interdisciplinary research environments.

Understanding Guided Acoustic Waves

To better appreciate the significance of this work, it helps to understand guided acoustic waves more broadly. These waves are commonly used in technologies such as surface acoustic wave sensors, which appear in applications ranging from smartphones to industrial sensing. What’s new here is the integration of topological protection, which dramatically improves localization and robustness.

Traditional acoustic sensors are sensitive to defects and environmental variations. By contrast, topological acoustic states can remain stable even when the system is imperfect, making them ideal for high-precision applications.

What Comes Next

Future research will likely focus on refining the sensor’s sensitivity, exploring different materials, and testing its performance in biological and quantum environments. If successful, this approach could redefine how scientists think about sensing at the smallest scales.

Rather than pushing hardware to its physical limits, this work shows how fundamental physics can offer entirely new paths forward.

Research Paper:

https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.14.L4Y3