Diamond Defects Paired Through Quantum Entanglement Are Transforming Nanoscale Magnetic Sensing

Scientists have long known that the most interesting physics often happens at extremely small length scales—far smaller than what conventional instruments can directly observe. Electric currents do not flow smoothly at these scales; instead, they hop between atomic sites. Magnetic fields twist and loop through crystal lattices in complex patterns. Until now, these processes have largely remained hidden, buried inside averaged measurements and indirect data. A new breakthrough from Princeton University is changing that picture by introducing a quantum sensor capable of directly probing these elusive fluctuations.

Researchers led by Nathalie de Leon, associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at Princeton, have developed a diamond-based quantum sensor that uses entangled pairs of atomic-scale defects to measure magnetic phenomena with unprecedented sensitivity. Reported in a paper published in Nature on November 27, the technique achieves roughly 40 times greater sensitivity than earlier diamond sensing methods. More importantly, it opens a new window into the physics of real materials such as graphene and superconductors, systems that underpin both cutting-edge research and future technologies.

How Diamond Defects Become Quantum Sensors

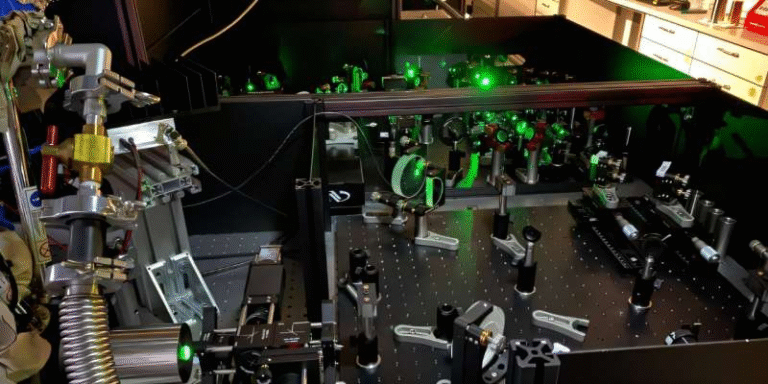

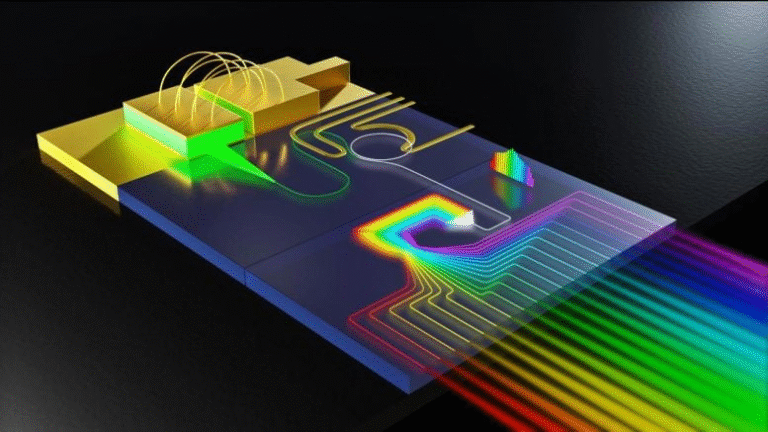

At the heart of this advance are tiny imperfections inside lab-grown diamonds known as nitrogen-vacancy centers, often shortened to NV centers. These defects form when one carbon atom is missing from the diamond lattice and is replaced by a nitrogen atom nearby. Although this sounds like a flaw, NV centers are extraordinarily useful. Their electron spins respond strongly to magnetic fields, and scientists can read out those spin states using light and microwave pulses.

Lab-grown diamonds used for quantum sensing are incredibly pure—far purer than most natural diamonds. Each NV center represents just one missing atom among billions, yet its quantum properties make it a powerful magnetic probe. Over the past decade, single NV centers have already been used to image magnetic fields from nanoscale currents, magnetic vortices, and even individual spins.

Traditionally, each NV center has been treated as an independent sensor, measuring local magnetic fields at a single point in space. While effective, this approach has fundamental limits. It captures averages but struggles to reveal correlations and fluctuations—the subtle relationships between magnetic signals at nearby locations.

Why Pairing Defects Changes Everything

The Princeton team took a bold step by placing two NV centers extremely close together, about 10 nanometers apart, roughly the width of a few dozen atoms. This tiny separation allows the two defects to interact through quantum-mechanical effects. Under the right conditions, they become quantum-entangled, meaning the state of one is directly linked to the state of the other.

Entanglement is often described as counterintuitive, but its practical benefit here is clear. Instead of acting like two separate sensors, the paired NV centers behave as a single, coordinated quantum system. This allows them to directly measure correlated magnetic noise, rather than inferring it indirectly through complex post-processing.

In simple terms, the two defects function like two eyes instead of one, giving depth perception to magnetic measurements. By comparing what both sensors experience at the same time, the system can pinpoint where fluctuations originate and how they evolve in space and time.

Implanting Defects with Atomic Precision

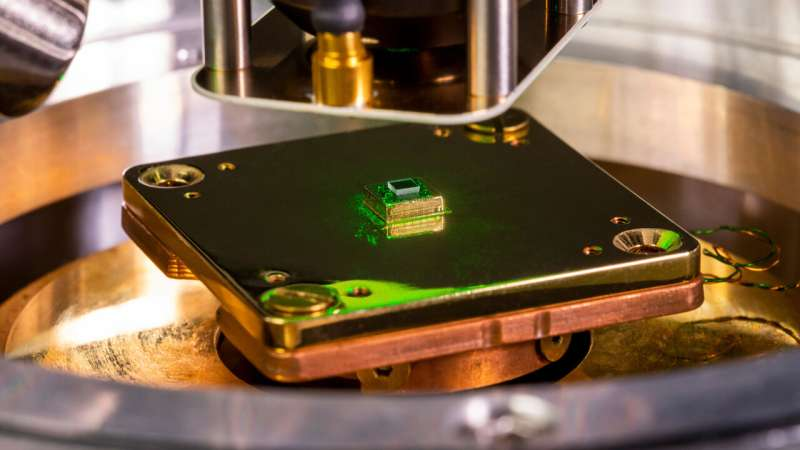

Creating such a sensor requires extreme control. The researchers implanted the NV centers by firing nitrogen molecules at enormous speeds—over 30,000 feet per second—into the diamond surface. On impact, the molecule breaks apart, sending its two nitrogen atoms into the crystal lattice.

By carefully tuning the energy of the incoming molecules, the team controlled how deep the nitrogen atoms penetrated. In this case, they stopped about 20 nanometers below the surface, ending up roughly 10 nanometers apart from each other. This precise spacing is critical: too far apart and the defects behave independently; too close and fabrication becomes unreliable.

The result is a pair of defects close enough to interact quantum mechanically while still probing slightly different points in space.

Revealing Hidden Magnetic Fluctuations

One of the most powerful aspects of this approach is its ability to expose signals hidden inside noise. In condensed matter systems, magnetic fluctuations often average out when measured with traditional techniques. These fluctuations still contain valuable information, but it is statistically buried.

Entangled NV pairs change that. Correlations between magnetic signals leave a direct “fingerprint” on the quantum state of the sensor. This allows researchers to detect whether fluctuations are related or independent, and to measure quantities such as correlation length, electron scattering distances, and the dynamics of magnetic vortices in superconductors.

This is especially relevant at length scales between individual atoms and the wavelength of visible light—a regime where many of the most important physical processes occur, yet few experimental tools can operate effectively.

A Theoretical Insight Turned Practical Breakthrough

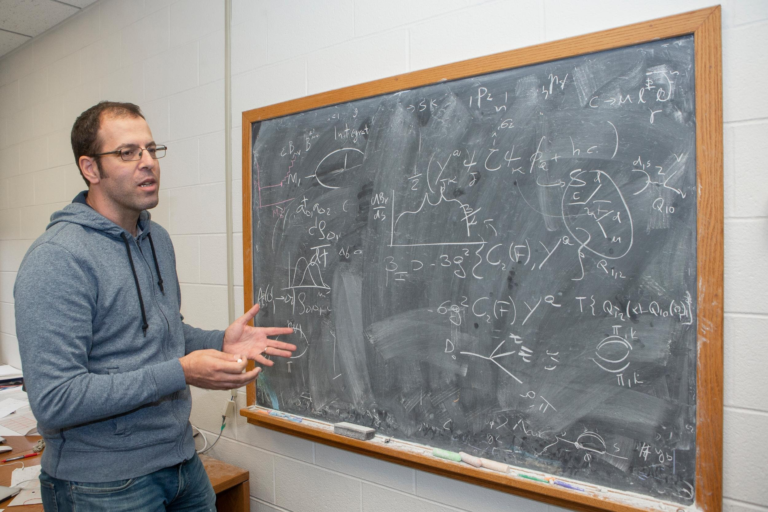

Interestingly, this advance did not begin as a purely experimental effort. Jared Rovny, who joined de Leon’s group in 2020 as a Princeton Quantum Initiative postdoctoral fellow, started thinking deeply about magnetic noise correlations during the COVID-19 lab shutdowns. Drawing on his background in nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), where interactions and correlations are central, he explored whether NV centers could be used in a similar way.

Early work examined correlations between non-entangled NV centers, leading to a 2022 paper in Science. While promising, those methods were technically complex and difficult to scale. The key realization was that entanglement simplifies everything. By entangling the NV centers, the presence or absence of correlations becomes directly encoded in the measurement, eliminating much of the experimental overhead.

The result is a system that effectively delivers two sensors for the cost of one, requiring only a single, straightforward measurement to extract correlated information.

Why This Matters for Real Materials

Experts in the field see this as a major step forward. Unlike earlier correlation-measurement techniques that relied on carefully engineered atomic arrays, this approach works on real materials—the messy, imperfect systems that physicists actually want to understand.

This makes it especially valuable for studying graphene, where electron behavior is highly sensitive to disorder and fluctuations, and superconductors, where magnetic vortices and noise play a key role in performance. These materials are central to technologies ranging from MRI machines to lossless power transmission and future quantum devices.

The Bigger Picture of Quantum Sensing

Quantum sensing is one of the most mature and practical branches of quantum technology. Unlike quantum computing, it does not require millions of qubits or full error correction. Instead, it leverages small, well-controlled quantum systems to achieve sensitivity beyond classical limits.

Entanglement has long been theorized as a resource for enhanced sensing, but practical demonstrations in solid-state systems have been challenging. This work shows that entanglement can deliver real, measurable advantages, even in noisy, real-world environments.

As fabrication techniques improve, future sensors may incorporate larger networks of entangled defects, pushing sensitivity and spatial resolution even further. That could allow scientists to map magnetic behavior inside materials with unprecedented clarity.

Looking Ahead

This paired-defect diamond sensor represents more than just an incremental improvement. It introduces a new way of thinking about nanoscale measurements, one that treats noise and fluctuations not as obstacles, but as sources of rich information. By turning a perceived weakness—magnetic noise—into a quantum advantage, the Princeton team has opened up an entirely new playground for condensed matter physics.

As researchers begin applying this technique to a wider range of materials, we are likely to learn far more about how electrons, spins, and magnetic fields behave at the smallest scales. For a field that has long relied on indirect clues, that is a very exciting development indeed.

Research paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09760-y