Nanoparticle-Based Vaccine Research Shows Promise for Broad Protection Against Ebola and Other Deadly Filoviruses

Filoviruses are among the most dangerous pathogens known to science. This virus family includes Ebola, Sudan, Bundibugyo, and Marburg viruses—names that are often associated with severe outbreaks, high fatality rates, and global health emergencies. Now, researchers at The Scripps Research Institute have taken an important step toward tackling this threat with a new nanoparticle-based vaccine strategy that could offer protection against multiple filoviruses at once.

The work, published in Nature Communications, focuses on overcoming one of the biggest challenges in filovirus vaccine development: the structure and behavior of the virus’s surface proteins. These proteins are notoriously difficult to target, and the new approach is designed specifically to make them easier for the immune system to recognize and respond to.

Why Filoviruses Are So Dangerous

Filoviruses get their name from the Latin word “filum,” meaning thread, which describes their long, filament-like shape. But their appearance is far less concerning than the diseases they cause. Infections with viruses like Ebola and Marburg can lead to viral hemorrhagic fever, a condition marked by severe bleeding, organ failure, and shock.

Fatality rates can reach up to 90% in some outbreaks. During the 2013–2016 Ebola epidemic in West Africa, more than 28,000 people were infected and over 11,000 lost their lives. While there are now two approved vaccines for Ebola, these vaccines mainly target specific strains and do not provide broad protection across the entire filovirus family.

This lack of broad coverage leaves the world vulnerable to future outbreaks caused by lesser-known or newly emerging filoviruses.

The Core Problem With Filovirus Vaccines

At the heart of the issue are the viruses’ surface glycoproteins. These proteins are essential for infection because they allow the virus to enter human cells. Unfortunately, they are also unstable, constantly changing shape, and heavily coated with sugars known as glycans.

This sugar coating acts like a molecular “invisibility cloak,” hiding critical regions of the protein—called epitopes—from the immune system. Even worse, when the virus enters a cell, the glycoprotein undergoes a dramatic shape change, shifting from a pre-fusion form to a post-fusion form. Most effective antibodies need to recognize the pre-fusion shape, but that form is fleeting and hard to study.

All of this makes designing vaccines that trigger strong, lasting immunity extremely difficult.

A Nanoparticle Strategy Designed to Help the Immune System

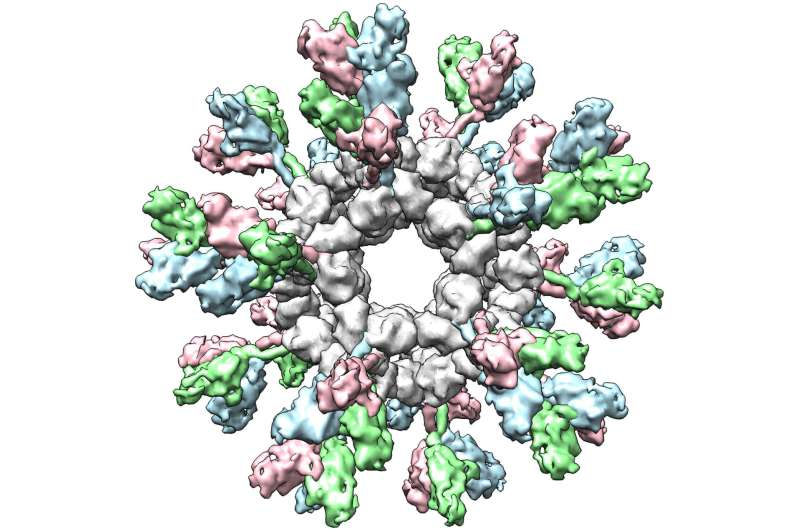

The new research from Scripps tackles these challenges using self-assembling protein nanoparticles, often referred to as SApNPs. These nanoparticles act as tiny scaffolds that can display viral proteins in a stable and highly organized way.

The researchers engineered filovirus glycoproteins so they remain locked in their pre-fusion form, which is the shape the immune system needs to see in order to mount an effective defense. These stabilized proteins were then attached to the surface of the nanoparticles, creating virus-like particles coated with multiple copies of the same antigen.

This design does two important things:

- It stabilizes the viral proteins so they don’t fall apart or change shape.

- It presents them repeatedly and clearly to the immune system, increasing the chance of a strong antibody response.

Building on Earlier Breakthroughs

This study builds on earlier work from the same research group. In 2021, the team published a detailed structural analysis of the Ebola virus glycoprotein. In that earlier research, they identified ways to stabilize the protein and remove certain mucin-rich regions that obscure important immune targets.

By trimming away these sections, the researchers created a cleaner version of the protein that was easier for immune cells to recognize. The new study expands this strategy beyond Ebola and applies it to multiple filovirus species, moving closer to the idea of a broadly protective filovirus vaccine.

What the Mouse Studies Revealed

To test their vaccine candidates, the researchers conducted experiments in mice. The results were encouraging.

Mice vaccinated with the nanoparticle-based formulations produced strong antibody responses that could recognize and neutralize several different filoviruses, not just one. This kind of cross-reactivity is critical if a vaccine is meant to protect against an entire virus family rather than a single strain.

The team also experimented with modifying the glycans on the glycoproteins. By adjusting these sugar molecules, they were able to expose conserved weak points on the virus—areas that are similar across different filoviruses and less likely to mutate. This further improved the immune response and reinforced the idea that glycan engineering could play a major role in future vaccine design.

The Role of Rational, Structure-Based Design

A key feature of this work is its reliance on rational, structure-based vaccine design. Instead of relying on trial and error, the researchers used detailed structural data to guide every step of the process.

They carefully analyzed how filovirus glycoproteins fold, where they are unstable, and which regions are most important for immune recognition. From there, they engineered proteins with the right shape, stability, and presentation to maximize immune effectiveness.

This approach reflects a broader shift in vaccine science, where advances in structural biology and computational modeling are enabling precision-designed vaccines for some of the world’s most challenging pathogens.

Beyond Filoviruses: Broader Implications

The nanoparticle platform used in this study is not new to the Scripps team. Similar strategies have already been explored for HIV-1, hepatitis C, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), human metapneumovirus (hMPV), and influenza.

Filoviruses represented a particularly difficult test case due to their heavy glycan shielding and protein instability. The success seen in animal models suggests that the platform could be adapted for other high-risk emerging viruses, especially those with similar structural challenges.

The researchers are already extending this work to viruses like Lassa virus and Nipah virus, both of which pose serious outbreak risks and currently lack widely effective vaccines.

What Still Needs to Be Solved

While the results are promising, the researchers are clear that challenges remain. Stabilizing the pre-fusion form of viral proteins is a major step, but it may only solve part of the problem. The dense glycan shields found on many viruses, including filoviruses and HIV, still limit how well the immune system can “see” key targets.

Developing methods to bypass or weaken this glycan shield without compromising safety will be crucial. According to the researchers, this is one of the next major goals in the effort to create truly universal vaccines.

Why This Research Matters

A broadly protective filovirus vaccine could dramatically improve global outbreak preparedness. Instead of racing to develop a new vaccine after each outbreak begins, health systems could rely on a platform that is already effective against multiple known threats—and potentially adaptable to new ones.

While human trials are still a future step, this study provides a strong scientific foundation for what could eventually become a next-generation defense against some of the deadliest viruses humanity faces.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-66367-7