New Experiments Are Revealing the True Source of Most of the Universe’s Visible Mass

Scientists have long known that protons and neutrons—the building blocks of atoms—contain quarks held together by gluons. But a major puzzle has persisted for decades: the masses of these particles are far larger than the masses of the quarks that make them up. New research from the Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility (Jefferson Lab) is now offering the most detailed explanation yet for this discrepancy, and the findings point to a remarkable truth about our universe: more than 98% of the mass of ordinary matter comes from a process completely different from the Higgs mechanism.

This latest work pulls together nearly 30 years of experimental results and cutting-edge theoretical modeling to map out how hadron mass—meaning the mass of strongly interacting particles like protons—is generated through the dynamics of the strong nuclear force. Researchers describe this phenomenon as the emergence of hadron mass, often shortened to EHM.

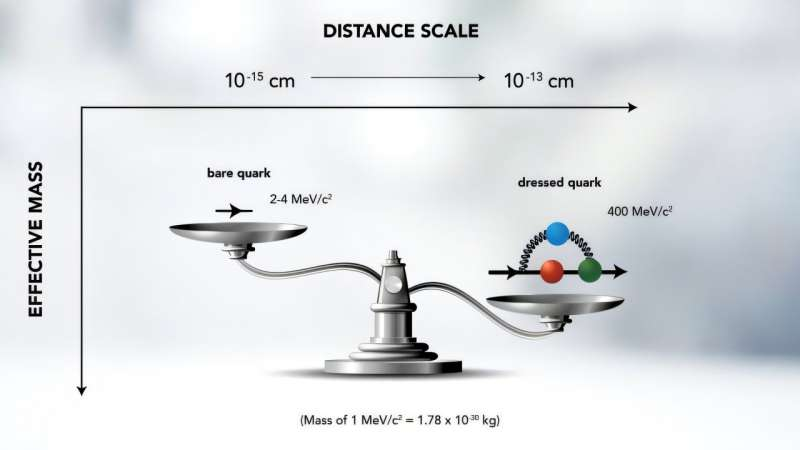

The Higgs mechanism gives quarks their bare masses, typically just a few million electron-volts (MeV). But the proton has a mass of roughly 1 billion electron-volts (1 GeV). Experiments confirm that Higgs-based quark masses contribute less than 2% of the total mass of real-world protons and neutrons. The remaining 98% arises from something else—something that emerges from the quantum interactions inside these particles.

The new research, which appears in the journal Symmetry, shows that the strong force, described by quantum chromodynamics (QCD), generates mass through the energy stored in quark-gluon fields. This energy becomes mass via Einstein’s familiar relationship, though the underlying processes are far richer and more complex than the simple equation suggests.

Understanding the Role of the Strong Force

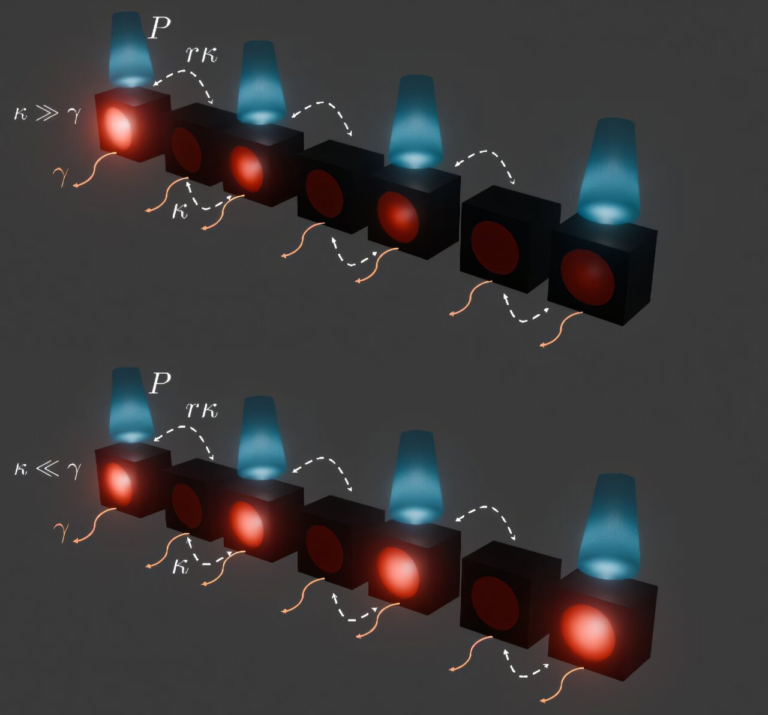

QCD governs how quarks and gluons interact. One of its unique features is gluon self-interaction—a behavior not seen in electromagnetic or gravitational forces. Because gluons can interact with one another, the strong force behaves very differently depending on distance. At extremely small distances, quarks behave almost freely. At distances comparable to the size of a proton—around 10⁻¹³ centimeters—the interactions become incredibly intense.

Here’s where things get interesting. At these scales, quarks and gluons are no longer the “bare” particles described in the Lagrangian of QCD. Instead, they become dressed quarks and dressed gluons, meaning they are surrounded by clouds of virtual particles that are constantly being created and annihilated.

This dressing process dynamically generates mass. A quark that weighs only a few MeV as a bare particle ends up behaving like it has an effective mass of about 400 MeV when dressed. That dramatic mass increase arises entirely from strong-interaction dynamics.

Combine three dynamically massive quarks in a proton, and the total mass comes out to roughly 1 GeV, matching what experiments observe. This same mechanism applies to excited states of the proton, which fall in the range of 1.0 to 3.0 GeV.

The Continuum Schwinger Method and What It Reveals

To probe this dynamic mass generation, researchers use a theoretical framework known as the continuum Schwinger method (CSM). This approach examines how the strong force changes with distance or momentum. When experimentalists collect data on how electrons scatter off protons and excite them into various resonances, theorists can compare those results with CSM predictions. If the theory correctly captures how quark mass evolves with momentum, the experimental signatures will align.

That’s exactly what’s been happening.

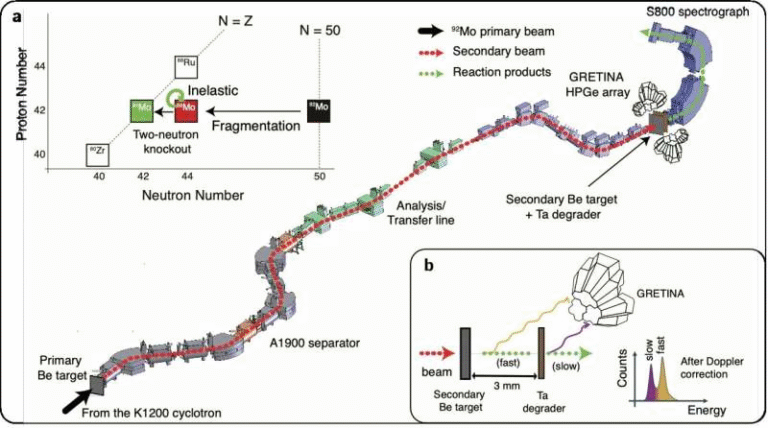

For decades, Jefferson Lab has been running experiments using its Continuous Electron Beam Accelerator Facility (CEBAF). Originally working with 6 GeV beams, the accelerator was later upgraded to 12 GeV, allowing access to a wider range of momentum transfers and deeper insight into proton structure.

A key part of this experimental program is CLAS12, a huge detector in Hall B capable of tracking many types of particles and covering a broad range of angles. By studying how electrons interact with protons and how the resulting resonances decay, researchers can extract detailed information about the internal structure of the proton and its excited states. These quantities, called electrocouplings, allow scientists to map out the momentum dependence of dressed-quark masses.

The latest analyses bring together results from CLAS, the older 6 GeV detector, and CLAS12. When compared with CSM predictions, the match is compelling: the data confirm that dressed quarks with dynamically generated masses truly are the building blocks of the proton and its excited states.

How Much of the Mass-Generating Picture Is Now Clear?

Experiments at 6 GeV mapped around 30% of the distance range where hadron mass emerges.

The ongoing 12 GeV program is expanding that coverage to about 50%.

Future facilities—possibly involving an energy upgrade to even higher electron beam energies—would allow scientists to map the entire region where hadron mass is formed. Completing this map would give physics a full, experimentally grounded explanation of where the mass of the visible universe comes from.

Why This Research Matters

Understanding the origin of mass is one of the deepest problems in physics. The Higgs mechanism explains the masses of fundamental particles, but as this work shows, it does not explain the mass of the matter we interact with every day.

Instead, mass is largely an emergent property of the strong interaction. It comes from:

- the kinetic energy of quarks

- the self-interactions of gluons

- the structure of the quark-gluon fields

- the rapid creation and annihilation of virtual quark-antiquark pairs

This is a striking example of emergence in physics—complex behavior arising from the interplay of simpler fundamental rules.

The current research is a highly cooperative effort involving experimentalists, theorists, and phenomenologists. Jefferson Lab scientists emphasize that this collaboration is essential, because no single type of measurement can unravel the full complexity of hadron mass generation.

Additional Background: How QCD Creates Mass

To add more context beyond the news:

1. Confinement

Quarks cannot exist freely; they’re always locked inside hadrons. This confinement contributes heavily to mass. Stretching the strong force field between quarks increases energy, and therefore mass.

2. Quantum fluctuations

Inside protons, the vacuum is active: quark-antiquark pairs pop in and out of existence. These fluctuations shape the proton’s structure.

3. The gluon field

Even though gluons are massless in the QCD Lagrangian, gluon self-interaction creates an effective mass scale. This supports the structure of hadrons and helps generate mass.

4. Dressed-quark mass curve

At high momenta, quarks behave almost masslessly. As momentum decreases, their effective mass rises sharply. Mapping this curve experimentally is a major goal of ongoing research.

Looking Forward

Jefferson Lab’s ongoing studies will continue refining the picture of how mass emerges. With future high-energy upgrades, researchers aim to fully map the mass-generation region and deepen the connection between theory and experiment. As physicists like to point out, the mass of the universe isn’t simply “there”—it’s constantly being generated by the intricate motions and interactions of quarks and gluons.

It’s a reminder that even everyday matter contains a deep, dynamic complexity that science is only now fully uncovering.

Research Reference:

Electroexcitation of Nucleon Resonances and Emergence of Hadron Mass (Symmetry, 2025)