New Image Sensor Breaks Optical Limits With Lensless Super-Resolution Imaging

Imaging technology has always shaped how we explore the world, from observing distant galaxies to examining microscopic structures inside living cells. Over the years, scientists have steadily improved cameras, microscopes, and telescopes, but one major limitation has remained stubbornly difficult to overcome: achieving high-resolution, wide-field optical imaging without bulky lenses or extremely precise physical alignment. A newly developed image sensor may finally change that.

Researchers at the University of Connecticut, led by biomedical engineering professor Guoan Zheng, have introduced a breakthrough optical imaging system that pushes past traditional optical limits. The technology, called the Multiscale Aperture Synthesis Imager (MASI), demonstrates that it is possible to achieve optical super-resolution using computation rather than lenses or rigid interferometric setups. Their work has been published in Nature Communications, signaling a significant advance in how optical imaging systems may be designed in the future.

Why Optical Imaging Has Been Stuck for So Long

Conventional optical systems rely heavily on lenses to focus light onto a sensor. Whether it is a smartphone camera, a microscope, or a telescope, lenses are the core components that determine resolution, field of view, and working distance. Unfortunately, these factors are tightly linked. Improving one often degrades another.

For example, resolving smaller details typically requires placing lenses very close to the object. This limits working distance and makes imaging difficult for delicate biological samples, forensic evidence, or industrial components. Large lenses can improve resolution, but they are expensive, heavy, and increasingly complex to manufacture.

Synthetic aperture imaging has long been viewed as a potential solution. This approach combines data from multiple sensors to simulate a much larger aperture. It famously enabled the Event Horizon Telescope to capture the first image of a black hole by linking radio telescopes across the globe. However, while this method works well at radio wavelengths, it becomes nearly impossible at visible light wavelengths. Optical light oscillates at extremely high frequencies, meaning sensors must be synchronized with nanometer-level precision, a requirement that is impractical outside tightly controlled laboratory conditions.

The Core Idea Behind MASI

MASI takes a fundamentally different approach to synthetic aperture imaging. Instead of forcing multiple optical sensors to operate in perfect physical synchrony, the system allows each sensor to work independently. The synchronization happens later, through computation.

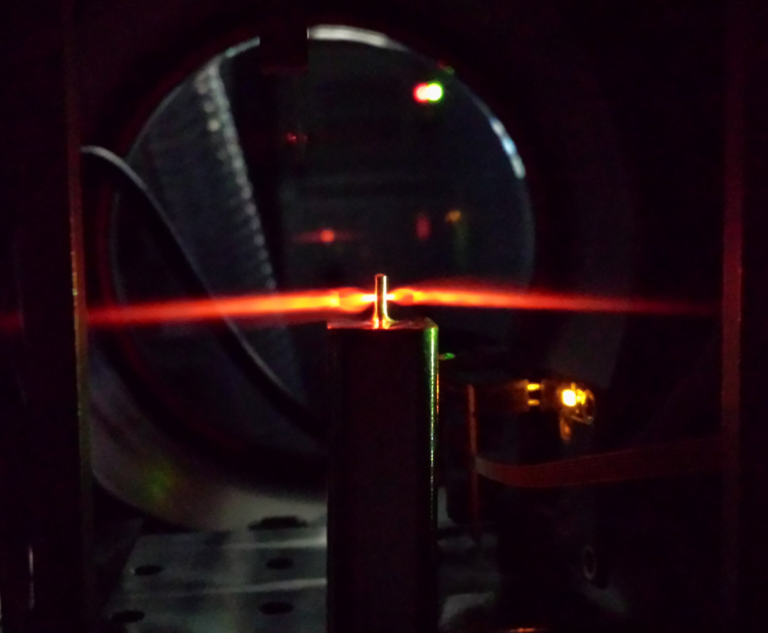

Rather than capturing focused images, MASI uses an array of coded sensors placed at different locations within a diffraction plane. Each sensor records raw diffraction patterns created when light interacts with an object. These patterns contain both amplitude information (brightness) and phase information, which describes how the light waves propagate.

Using advanced computational algorithms, the system reconstructs the complex wavefield captured by each sensor. Once this data is recovered, the wavefields are digitally padded and numerically propagated back to the object plane. At this stage, MASI applies a computational phase synchronization process that iteratively adjusts the relative phase offsets between sensors. The algorithm works to maximize coherence and energy in the combined reconstruction.

This software-driven phase alignment is the key innovation. By removing the need for rigid physical alignment, MASI bypasses the constraints that have historically blocked optical synthetic aperture systems from real-world use.

What Makes MASI Different From Conventional Imaging

MASI departs from traditional optical imaging in two major ways. First, it does not rely on lenses at all. There is no focusing element between the object and the sensors. Second, it captures and reconstructs the full wave nature of light rather than just intensity.

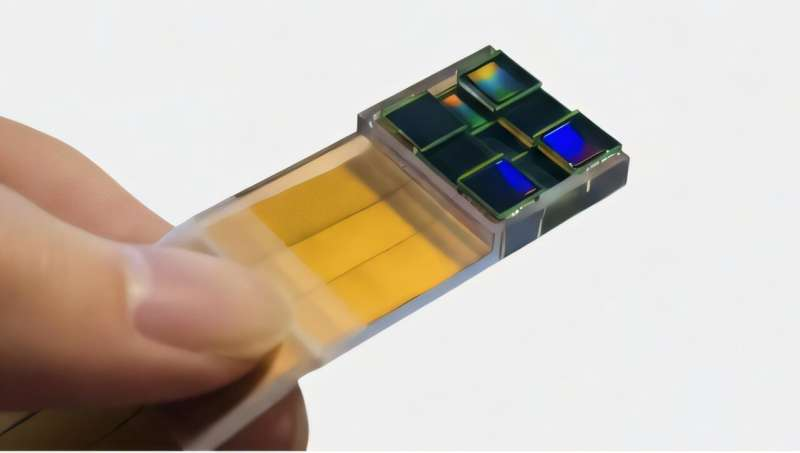

Because MASI digitally combines measurements from multiple sensors, it effectively creates a virtual synthetic aperture much larger than any single sensor. This allows the system to surpass the diffraction limit that normally constrains optical resolution. The result is sub-micron resolution over a wide field of view, achieved without lenses and without placing sensors extremely close to the object.

In demonstrations, MASI has shown the ability to reconstruct three-dimensional structures at micrometer resolution. One striking example involves imaging a bullet cartridge. The reconstructed image clearly reveals the firing pin impression, a microscopic marking used in forensic science to link ammunition to a specific firearm. This level of detail was achieved from a distance of several centimeters, something that would be very difficult with conventional optical systems.

Practical Advantages Over Traditional Optics

Traditional optical systems force designers into constant trade-offs. High resolution usually comes at the cost of working distance, field of view, or system complexity. MASI breaks this pattern.

Because the system captures diffraction patterns rather than focused images, it can operate farther away from the object while still achieving high resolution. This makes it especially attractive for applications where close proximity is undesirable or impossible.

Another major advantage is scalability. As optical systems grow larger, their complexity typically increases exponentially. In contrast, MASI scales linearly. Adding more sensors increases imaging capability without introducing overwhelming mechanical or optical challenges. This opens the door to large sensor arrays that could be adapted for a wide range of scientific and industrial tasks.

Potential Applications Across Multiple Fields

The flexibility of MASI makes it relevant to many disciplines. In biomedical imaging, lensless, high-resolution systems could enable non-invasive diagnostics or simplify the design of compact imaging devices. In forensic science, the ability to capture fine surface details from a distance could improve evidence analysis while preserving samples.

Industrial inspection is another promising area. Manufacturers often need to inspect micro-scale defects on components without stopping production or dismantling machinery. MASI’s long working distance and high resolution make it well suited to this challenge.

The system could also impact remote sensing and scientific imaging, where traditional optics struggle with size, weight, and alignment constraints. By shifting complexity from hardware to software, MASI aligns well with the broader trend toward computational imaging.

Understanding the Broader Context of Computational Imaging

MASI is part of a growing movement in imaging science where computation replaces physical components. Similar ideas are already used in areas like computational photography, holography, and light-field imaging. What makes MASI notable is that it applies these principles to overcome what were previously considered fundamental optical barriers.

By decoupling measurement from synchronization, MASI shows that limits imposed by traditional optics are not absolute. Instead, they can be redefined when light is treated as a wavefield that can be reconstructed and optimized computationally.

Why This Matters Going Forward

The Multiscale Aperture Synthesis Imager represents more than a new sensor design. It demonstrates a shift in how optical systems can be built, moving away from heavy reliance on precision hardware and toward software-driven intelligence. As computational power continues to grow, systems like MASI are likely to become more practical, more affordable, and more widespread.

For researchers, engineers, and technologists, this approach opens up a new design space for imaging systems that are high-resolution, flexible, and scalable. It suggests a future where optical limits are not removed by better lenses, but by better algorithms.

Research paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-65661-8