Physicists Find a Way to Produce Dark Matter Candidates in Fusion Reactors Once Thought Impossible

Physicists have long been chasing one of the universe’s biggest mysteries: dark matter. While it makes up most of the matter in the universe, it has never been directly observed. Now, a new theoretical study suggests that future fusion reactors could help generate one of the most promising dark matter candidates — axions — solving a problem that even fictional TV physicists couldn’t crack.

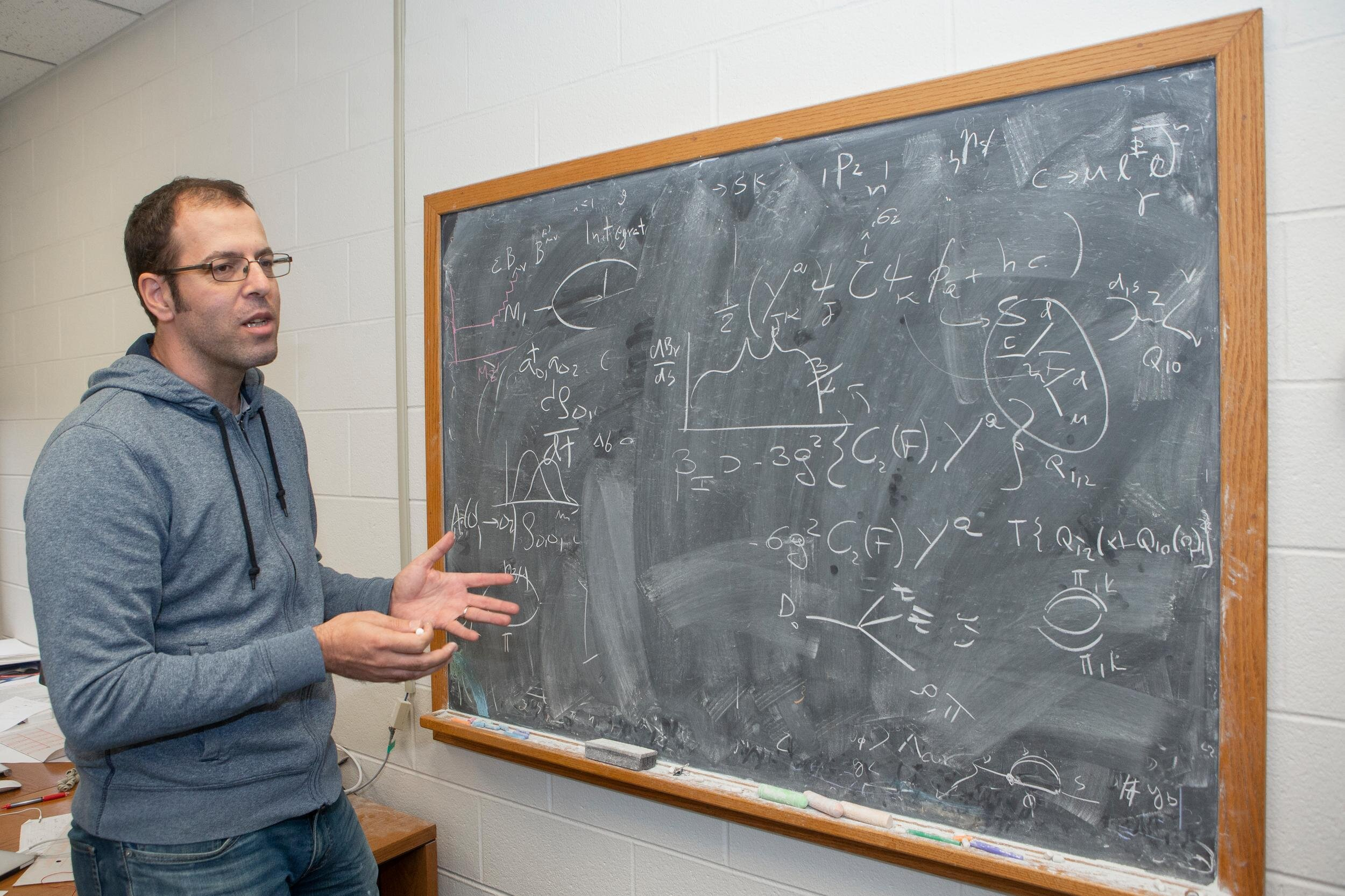

The research is led by Jure Zupan, a professor of physics at the University of Cincinnati, working alongside collaborators from Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, MIT, and the Technion–Israel Institute of Technology. Their findings were published in the Journal of High Energy Physics, and they offer a detailed theoretical explanation of how axions or axion-like particles could be produced inside nuclear fusion facilities.

What Are Axions and Why Do Physicists Care?

Axions are hypothetical subatomic particles that were first proposed decades ago to solve a problem in particle physics related to symmetry. Over time, physicists realized that axions had another extremely interesting feature: they could be an excellent explanation for dark matter.

Dark matter is believed to account for most of the matter in the universe, far outweighing the normal matter that makes up stars, planets, and people. It doesn’t emit, absorb, or reflect light, which is why it’s called “dark.” Scientists know it exists mainly because of its gravitational effects, such as how it influences the movement of galaxies and stars.

Because axions would be very light and weakly interacting, they fit many of the requirements physicists expect dark matter particles to have. However, detecting them has been notoriously difficult.

Why Fusion Reactors Enter the Picture

Fusion reactors are primarily designed to produce clean energy by fusing light atoms such as deuterium and tritium. But according to this new research, they may also double as laboratories for exploring new physics.

The team focused on a specific type of fusion reactor design currently under development through an international collaboration in southern France. This reactor uses deuterium and tritium fuel inside a vessel lined with lithium.

Fusion reactions in such reactors generate a massive number of high-energy neutrons. These neutrons are key to the researchers’ idea.

Two Ways Fusion Reactors Could Produce Axions

The study outlines two main mechanisms by which axions or axion-like particles could be produced inside fusion reactors.

1. Neutron Interactions with Reactor Walls

When high-energy neutrons slam into the materials lining the reactor walls, particularly lithium, they trigger nuclear reactions. These reactions can release energy in unusual ways, potentially creating new, exotic particles that belong to the so-called dark sector.

According to the theoretical models, axions could emerge as byproducts of these nuclear processes. While such events would be rare, the enormous number of neutrons produced in a fusion reactor means the overall effect could still be significant.

2. Neutron Bremsstrahlung (Braking Radiation)

The second mechanism involves a process known as bremsstrahlung, or “braking radiation.” As neutrons bounce off other particles and slow down, they release energy. Under the right conditions, this energy release could also produce axions or axion-like particles.

This approach differs from how axions are thought to be produced in stars like the Sun, and it turns out to be crucial.

Why Previous Attempts Fell Short

Interestingly, this exact problem appeared years ago in the TV show The Big Bang Theory, where the characters Sheldon Cooper and Leonard Hofstadter attempted to calculate axion production in fusion reactors. In the show, their equations famously led to failure.

The reason, according to real-world physics, is that they were effectively using solar-style axion production models. The Sun is a massive object producing an immense amount of energy, so axions generated there would vastly outnumber anything a fusion reactor could create using the same processes.

The new study shows that fusion reactors can work — but only if different physical processes are considered, specifically neutron-based interactions rather than solar-like mechanisms.

Detecting the Particles: Still a Challenge

Even if fusion reactors do produce axions, detecting them remains extremely difficult. Axions interact so weakly with normal matter that most of them would pass straight through reactor walls and detectors without leaving a trace.

However, the researchers suggest that dedicated detectors placed near fusion facilities could look for subtle signals. Over time, these experiments could help physicists either detect axions directly or place strong limits on how axions interact with ordinary matter.

Long-term experiments running for months or even years might be able to provide some of the most sensitive tests yet for axion-like particles.

Why This Matters Beyond Dark Matter

This research highlights a broader and increasingly important idea in physics: large-scale scientific facilities can often do more than one job.

Fusion reactors are built to solve humanity’s energy problems, but they may also become powerful tools for exploring fundamental physics. Similar cross-disciplinary benefits have already come from particle accelerators and astrophysical observatories.

If fusion reactors can indeed help probe dark matter, they would open an entirely new experimental frontier — one that operates alongside traditional underground detectors and space-based observations.

Extra Context: Why Axions Remain So Popular

Among all dark matter candidates, axions are especially attractive because they arise naturally from existing theories rather than being invented solely to explain dark matter. They also avoid many problems associated with heavier dark matter particles, such as conflicts with astrophysical observations.

Numerous experiments worldwide are already searching for axions using magnetic fields, resonant cavities, and astrophysical measurements. Adding fusion-based searches would significantly expand the toolkit available to physicists.

A Small Step With Big Implications

It’s important to note that this study is theoretical, not experimental. No axions have been detected in fusion reactors yet. Still, the work provides a detailed roadmap showing that such searches are physically plausible, something that was previously uncertain.

In short, physicists now have a mathematically sound answer to a question that once ended in a sad face on a sitcom whiteboard. Whether nature actually cooperates remains to be seen, but the path forward is clearer than ever.

Research paper:

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/JHEP10(2025)215