Quantum Simulations Reveal Hidden Chemical Reactions Inside Ice When UV Light Strikes

Scientists have uncovered new details about what really happens inside ice when it’s hit by ultraviolet light, and the findings are far more complex than previously imagined.

A team from the University of Chicago’s Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering, working with collaborators at the Abdus Salam International Center for Theoretical Physics in Trieste, used advanced quantum-mechanical simulations to map out the chemical changes occurring inside ice at a sub-atomic level. Their work helps explain puzzling experimental results dating back to the 1980s and sheds light on processes that matter for everything from melting permafrost on Earth to chemistry on distant icy moons.

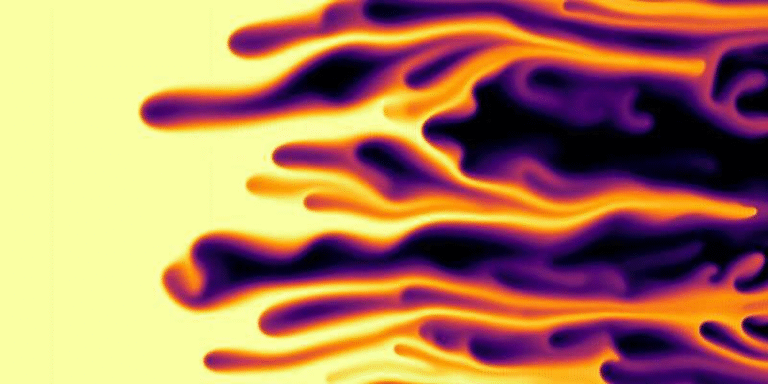

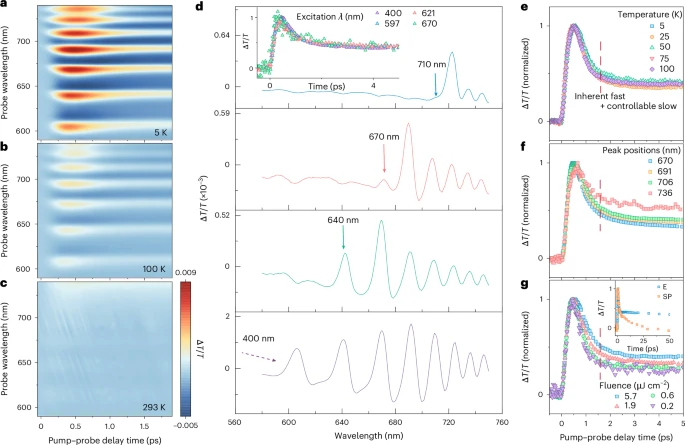

At the heart of the study is a long-standing mystery: when researchers exposed ice to UV light for only a few minutes, it absorbed certain wavelengths, but when the exposure lasted hours, the absorption pattern changed dramatically. For decades, this hinted that the chemistry of the ice was somehow transforming over time, but no one had the tools to pinpoint exactly what was going on. Ice may seem simple, but it turns out to be surprisingly difficult to study because UV light can break chemical bonds inside it, creating new molecules, ions, and free electrons. Each of these microscopic changes alters the way ice interacts with light, creating a kind of feedback loop of chemistry.

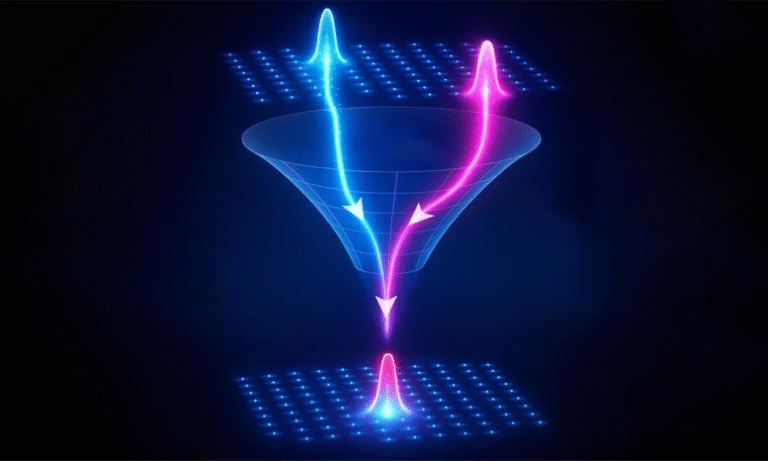

To tackle this, the team used sophisticated computational methods developed in recent years to study quantum materials. These tools let them simulate ice with a level of detail that previously wasn’t possible. Instead of trying to measure these changes experimentally—where isolating specific types of chemical defects is nearly impossible—they recreated ice structures digitally and introduced controlled imperfections.

They examined four versions of ice: a perfect, defect-free crystal, and three altered forms that included a vacancy where a water molecule was missing, charged hydroxide ions inserted into the lattice, and Bjerrum defects, which occur when ice’s usual hydrogen-bonding rules are broken so that either two hydrogen atoms sit between a pair of oxygen atoms or none at all. These defects sound tiny, but at the atomic level they can dramatically change how ice responds to UV light.

What the researchers discovered is that each defect leaves behind a unique optical signature, almost like a fingerprint. These signatures change how ice absorbs and emits UV light. In defect-free ice, UV absorption begins at one energy level. Introduce hydroxide ions, and the absorption starts at a different energy. Add Bjerrum defects, and the changes are even more dramatic, offering a strong match for the unexplained features experimentalists saw in ice that had been irradiated for long periods.

Because of these simulations, there’s now a clearer explanation for the decades-old puzzle: as UV light shines on ice, it causes chemical changes that gradually introduce new defects, altering the ice’s optical behavior over time. The longer the exposure, the more defects form, and the more the absorption pattern shifts. It’s not just about ice “warming up”—it’s about ice chemically evolving under UV radiation.

The team also mapped out the molecular reactions happening inside the ice. When UV light hits, water molecules can split apart into hydronium ions, hydroxyl radicals, and free electrons. Depending on what defects are present, these electrons either travel through the ice or become trapped inside tiny cavities. This trapping or movement influences what new chemical products form and how long they persist.

What makes this especially valuable is that the simulations finally give researchers something concrete to look for. Each defect’s optical signature provides a target for experiments on real ice samples. With this guide, scientists can design more precise measurements instead of guessing what might be happening invisibly inside the structure.

And while this study mainly focuses on the fundamental physics and chemistry of ice, the implications go well beyond the lab. One major area is melting permafrost. In the Arctic and other cold regions, permafrost traps large quantities of greenhouse gases such as methane and carbon dioxide. As global temperatures rise and sunlight reaches these icy layers, molecular reactions triggered by UV light may play a role in how quickly these gases are released. Knowing how ice responds to UV light—and what defects form—can improve predictions about the stability of permafrost and its contribution to climate change. Even tiny shifts in chemical behavior at the atomic level can scale up to impactful environmental effects.

Another important connection is astrochemistry. Many planetary bodies in our solar system, such as Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus, have thick layers of ice constantly bombarded by UV radiation. If UV-induced defects in the ice modify how molecules form and move, this could influence surface chemistry, plume composition, or even the formation of more complex organic molecules. Understanding these processes helps scientists better interpret observations from spacecraft and telescopes, and could contribute to discussions about habitability or prebiotic chemistry on icy worlds.

Although the results are promising, the researchers emphasize that this is only the beginning. Real ice contains multiple defects simultaneously, along with dust, gases, and other impurities—not just one defect type at a time. It also forms surfaces, cracks, and boundaries, which can behave differently from bulk ice. The next step is to simulate more realistic combinations of defects and compare them directly with experimental data. The team is already working with experimental scientists to design studies that test these predictions in actual ice samples.

To give more context, it’s helpful to understand what makes ice such a complex material. Even in its simplest form, ice has a structured arrangement known as ice Ih, the familiar hexagonal shape that snowflakes and frozen water often exhibit. Each water molecule participates in a network of hydrogen bonds that give ice its solid structure. But these hydrogen bonds aren’t perfect. Even in nature, ice naturally forms defects. Bjerrum defects, for example, occur because hydrogen atoms can shift slightly, breaking the usual “one hydrogen per bond” rule. Vacancies appear when a water molecule slips out of place. Ions like hydroxide can sneak into the lattice. All of these tiny imperfections influence how ice behaves at low temperatures, under pressure, or when exposed to radiation.

The study’s emphasis on defect-controlled photochemistry highlights something that scientists in materials science have known for a long time: defects are not flaws, they are functional features. They determine conductivity in semiconductors, reactivity in catalysts, and now, as this research shows, light-driven chemistry in ice.

Finally, the computational approach used in this research represents a major advancement. Traditional experiments struggle to capture events happening on femtosecond timescales (one quadrillionth of a second) or at the scale of single molecules breaking apart. But quantum simulations can pause, rewind, and analyze each step in these microscopic processes. This makes it possible to study not only the final products but the full pathway of how water molecules fragment and reassemble under UV light.

This is what makes the new findings so powerful: they don’t just show the end result—they reveal the hidden steps that ice undergoes when light interacts with it.

As the team continues to build more complex models and compare them with real-world samples, scientists hope to develop a comprehensive picture of ice photochemistry, both on Earth and in space. Understanding how ice evolves under radiation—how it releases gases, forms radicals, traps electrons, or creates new molecules—can transform how we model climate processes, planetary surfaces, and environmental change.

Research Paper:

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2516805122