Researchers Show How Embracing Chaos Could Give Synthetic Materials Lifelike Movement

Scientists have long admired the way living tissues move. Muscles twitch, hearts beat, and cells constantly shift and respond, all while being soft, flexible, and remarkably powerful. By contrast, most synthetic materials—even advanced soft ones—tend to move slowly and predictably, losing energy as they go. Now, new research from the University of Michigan suggests that the key to closing this gap may lie in something engineers usually try to avoid: chaos.

A team of physicists and engineers has developed a theoretical framework showing how synthetic soft materials could produce fast, energetic, and lifelike motions such as shivering and twitching. Their findings were published in the journal Physical Review Letters and point toward a future where soft machines behave less like rubber bands and more like living tissue.

Why Living Tissue Is So Hard to Replicate

When people think of powerful machines, they often picture engines, motors, or high-performance cars. But in physics, power is defined as how quickly energy is used or transferred—and by that definition, muscles are incredibly powerful systems. A muscle fiber can contract and relax rapidly, generating force in a fraction of a second.

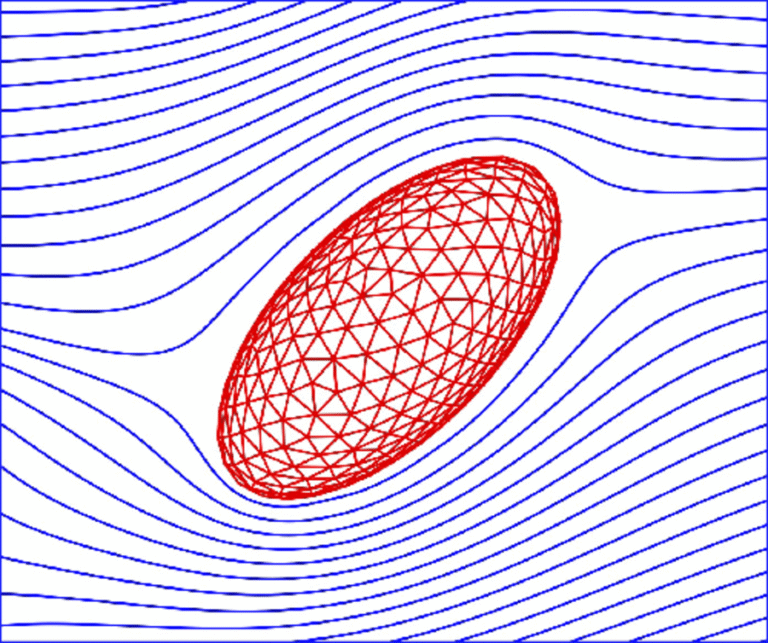

Synthetic soft materials, such as gels or elastomers, are excellent at being lightweight and flexible, but they usually lack this kind of speed and intensity. When stretched or deformed, they slowly return to their original shape as energy is dissipated through internal friction, a process known as damping. This damping overwhelms inertia, preventing rapid or sustained motion.

According to the researchers, this fundamental limitation has been one of the biggest obstacles in designing soft engines, soft robots, and active materials that can truly rival biological systems.

Turning a Weakness Into a Strength

The new model challenges a long-standing assumption in soft-matter physics: that inertia doesn’t really matter in soft materials. Normally, inertia—the resistance to changes in motion—is ignored because damping dominates the system. But the University of Michigan team found that inertia can become crucial if the material is designed in the right way.

The key idea is to couple a material’s mechanics with its internal chemistry. Instead of being passive, the material contains chemical reactions that actively supply energy. These reactions are not constant; they are sensitive to mechanical stress and strain. When the material is stretched, compressed, or deformed, the chemical reactions respond—and in turn, those reactions feed energy back into the mechanical motion.

This creates a positive feedback loop between force and chemistry. Rather than motion being damped out, the feedback counteracts dissipation and allows inertia to play a significant role. Under the right conditions, this interaction drives the system into complex, highly dynamic behavior.

When Motion Becomes Chaotic

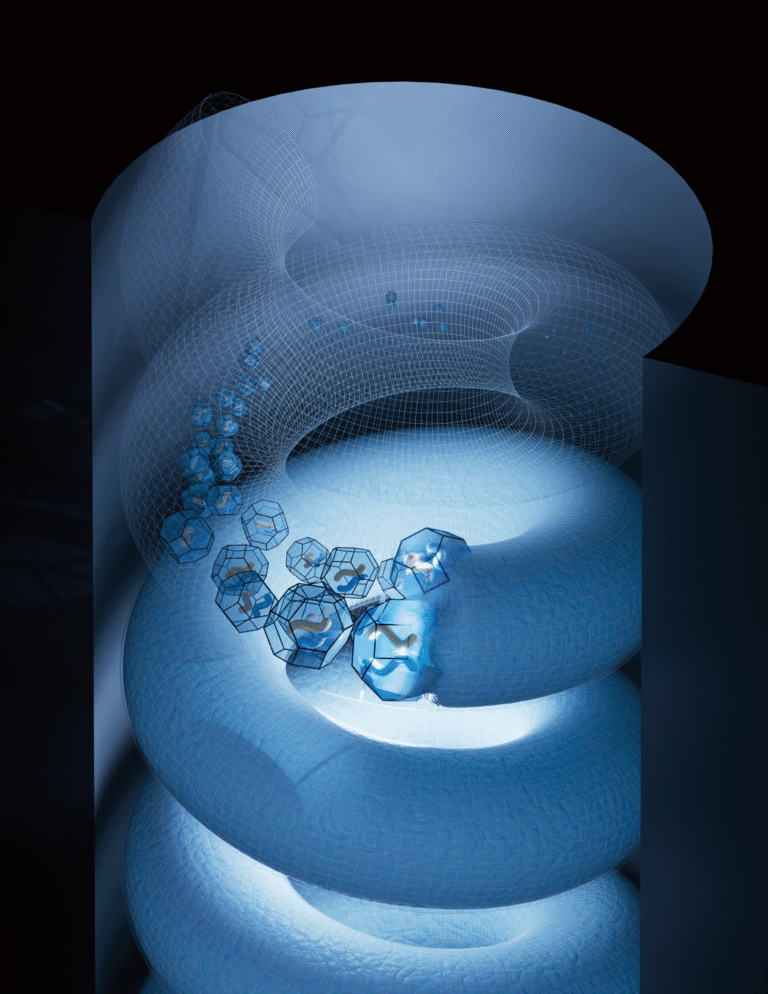

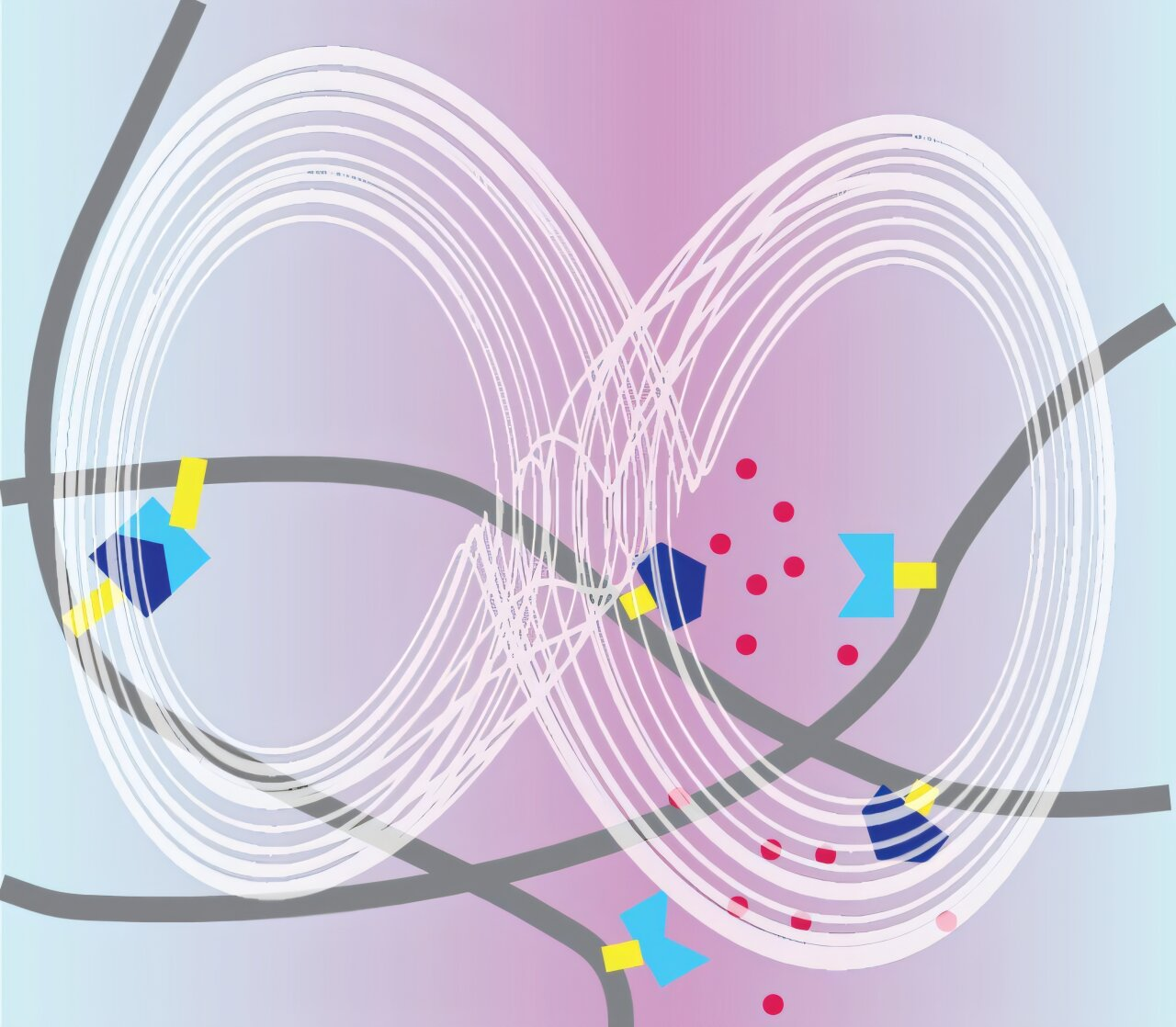

One of the most striking predictions of the model is that, when the feedback loop is strong enough, the material’s motion becomes chaotic in a mathematical sense. This doesn’t mean random or noisy. Instead, chaotic motion follows precise physical laws but never exactly repeats itself, even if it remains confined within a certain range of movement.

In the researchers’ simulations, this chaos appears as motion constrained within a figure-eight–like space that never returns to its starting point. Physically, this could look like a gel that shivers, twitches, or pulses—movements that feel far more biological than mechanical.

This kind of chaos is common in living systems, from heart rhythms to neural activity. The study suggests that such complexity may not be a flaw but a feature required for lifelike performance.

Chemical Energy as the Driving Force

At the heart of this framework is the idea that chemical reactions act as internal engines. Living cells constantly convert chemical energy into mechanical work, and the researchers argue that synthetic materials must do the same if they are to move like biological tissues.

Crucially, these chemical reactions must respond directly to mechanical forces. When stress alters reaction rates, and those reactions then modify stiffness, tension, or motion, the system becomes self-sustaining. Instead of gradually settling down, the material stays active.

The researchers note that individual elements of this feedback cycle already exist in experimental systems. Some materials change color when squeezed because stress activates a chemical response. Others can bend, swell, or move when a reaction takes place inside them. What has not yet been achieved is combining all of these components into a single material that fully realizes the feedback-driven dynamics described in the model.

Who Was Behind the Study

The work was led by Suraj Shankar, an assistant professor of physics at the University of Michigan, with Xiaoming Mao, a professor of physics, serving as the senior author. Biswarup Ash, a research fellow, contributed key insights into the role of inertia. Additional contributors include Siddhartha Sarkar, Nicholas Boechler from the University of California, San Diego, and Yueyang Wu, who worked on the project as an undergraduate researcher.

The research was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation, the U.S. Army Research Office, and the Office of Naval Research, highlighting the broad interest in active and adaptive materials.

Why This Matters for Soft Robotics and Beyond

If materials based on this framework can be realized experimentally, the implications could be significant. Soft robotics is an obvious area of impact. Current soft robots are often slow and limited in force, but materials that twitch or pulse on their own could lead to machines that move faster, respond more naturally to their environment, and operate with fewer rigid components.

Beyond robotics, such materials could enable new types of engines, adaptive structural components, or responsive medical devices. Imagine implants or prosthetics that actively adjust their stiffness, or materials that absorb and release energy in complex ways depending on how they are stressed.

Understanding Active Matter More Broadly

This study also contributes to the growing field of active matter, which explores systems that continuously consume energy to maintain motion or structure. Examples range from flocks of birds and bacterial colonies to synthetic particles driven by chemical fuel.

What sets this work apart is its focus on inertial dynamics in soft solids, an area that has been largely overlooked. By showing that inertia can generate rich behavior when combined with mechanochemical feedback, the researchers open up new theoretical and experimental directions.

What Comes Next

The researchers emphasize that their work is currently theoretical, providing a roadmap rather than a finished product. However, they are optimistic that advances in smart chemistry and material design could soon make it possible to build real systems that follow these principles.

If successful, future materials may no longer aim to suppress chaos but to embrace it, using complexity and feedback to achieve movements once thought exclusive to living organisms.

Research paper:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.18272