Scientists Discover How Single Filaments Can Tie Themselves Into Knots While Falling Through Fluids

Knots show up everywhere in daily life and science, from tangled earphones and climbing ropes to the tightly packed DNA inside viruses. Yet for decades, one fundamental question has puzzled physicists: how can a single, isolated filament form a knot all by itself, without bumping into anything or being actively twisted or shaken?

A new study from researchers at Rice University, Georgetown University, and the University of Trento in Italy finally provides a clear and surprising answer. The research reveals that gravity and fluid motion alone can drive knot formation in a lone filament as it sinks through a viscous fluid. The findings were published in Physical Review Letters and offer fresh insight into polymer physics, biological systems, and materials design.

A Longstanding Puzzle in Soft-Matter Physics

Knots usually form when objects collide, twist, or are deliberately manipulated. That makes sense for shoelaces, cables, or ropes. But in soft-matter physics, scientists have long known that polymers such as DNA and proteins can also become knotted, even in environments where collisions are rare or controlled.

What remained unclear was how a single filament, floating freely in a fluid and subject only to gravity, could ever generate the complex geometry required to knot itself. Intuition suggests that a filament would simply fall straight down or bend gently, not loop over itself in a precise way.

This new study shows that intuition was incomplete.

How Gravity and Fluids Work Together

Using Brownian dynamics simulations, the researchers modeled a semiflexible filament falling through a viscous fluid under strong gravitational forces. These conditions are similar to what polymers experience during ultracentrifugation, a technique widely used in laboratories.

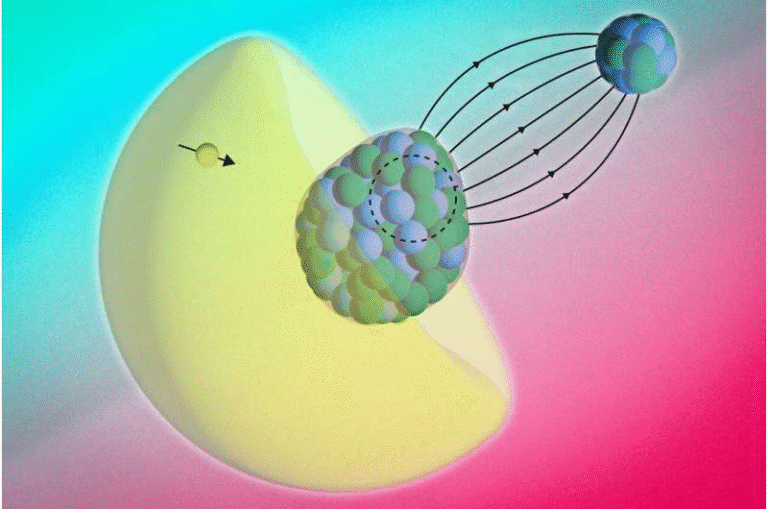

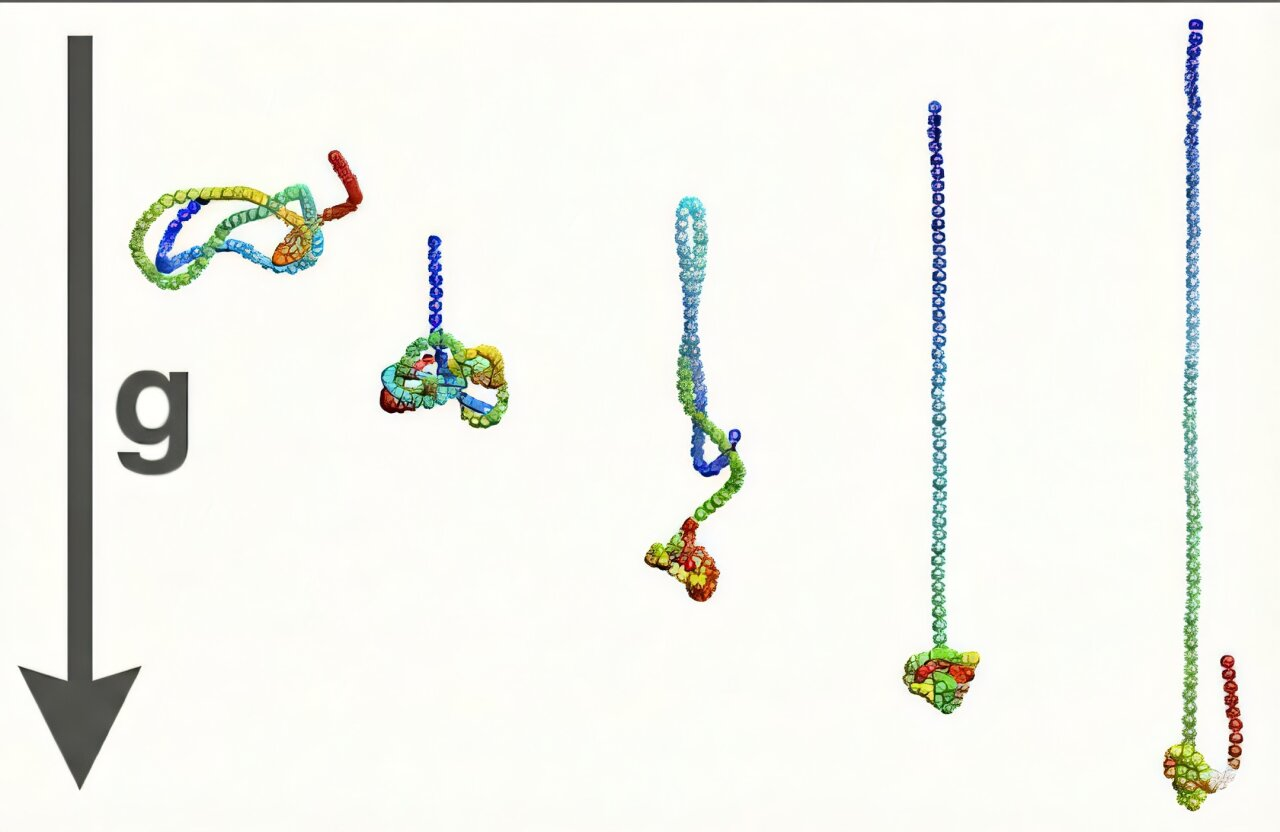

The simulations revealed a key mechanism driven by long-range hydrodynamic interactions. As the filament sinks, it does not move uniformly. Instead, the surrounding fluid generates complex flow patterns that bend and distort the filament.

Over time, part of the filament compresses into a dense, compact “head”, while the remaining length stretches into a long trailing tail. This uneven shape is crucial. The compact head creates regions where loops can form, while the trailing tail supplies length that can pass through those loops.

Under the right conditions, these loops cross and lock, producing stable knots without any external intervention.

Knots That Evolve and Tighten Over Time

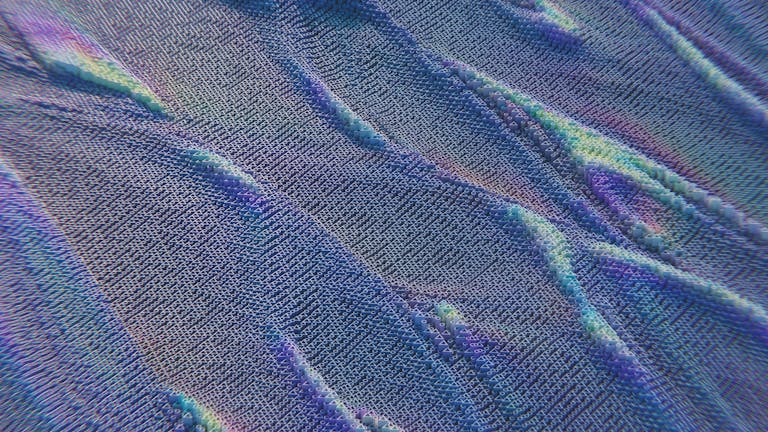

One of the most interesting findings is that the knots do not appear suddenly or randomly. Instead, they form through a hierarchical process.

Initial loose loops gradually rearrange, tighten, and reorganize into more complex and stable knot configurations. This process resembles annealing, where materials slowly settle into lower-energy, more stable states.

Once formed, the knots can persist for long periods. They are stabilized by tension along the filament, hydrodynamic drag from the surrounding fluid, and friction between different parts of the filament. Together, these effects prevent the knot from easily slipping apart.

Why Gravity Strength and Flexibility Matter

The simulations showed that stronger gravitational fields significantly increase both the likelihood and stability of knot formation. As gravity increases, the forces acting on the filament intensify, amplifying the hydrodynamic flows that drive bending and folding.

Flexibility also plays a major role. More flexible filaments can form a wider variety of knot types, while stiffer filaments are more limited. However, one surprising result is that even relatively short or stiff filaments—which were previously thought incapable of knotting—can still form tight, long-lived knots under sufficiently strong field conditions.

This finding challenges long-standing assumptions in polymer physics, where knotting was typically associated only with very long chains.

Why Knotting Matters in Biology

Knot formation is not just a theoretical curiosity. In biology, polymer knotting has real functional consequences.

DNA strands, for example, are packed into extremely small spaces inside viruses and cells. Knots can influence how DNA replicates, how it is transcribed into RNA, and how it moves through cellular machinery. In some contexts, knotting is beneficial, helping stabilize structures. In others, especially in genomic DNA, knots can be harmful and interfere with normal biological processes.

Proteins can also form knots that affect how they fold and function. Understanding how knots arise naturally under physical forces helps scientists better interpret these biological behaviors.

Implications for Materials Science and Engineering

Beyond biology, the study opens new possibilities in materials science and nanotechnology.

Traditionally, creating knotted polymers in the lab requires complex manipulation, chemical tricks, or what researchers sometimes call “knot factories.” The new findings suggest a different approach: letting gravity and fluid flow do the work.

By carefully controlling field strength, fluid viscosity, and filament flexibility, scientists could potentially design materials whose mechanical properties are determined by topology, not just chemical composition. Knotted polymers can exhibit increased strength, resilience, or unique deformation behaviors.

This approach could lead to patterned nanomaterials, mechanically reinforced fibers, and improved separation techniques in industrial and laboratory settings.

Connecting Theory With Experiment

Another important contribution of this research is that it bridges a long-standing gap between knot theory and experimental polymer physics.

Theoretical studies of knots often focus on idealized, tightly knotted structures, while experiments struggle to produce such configurations in controlled ways. This work suggests an experimentally achievable method for generating tight, complex knots in relatively short polymers, making direct comparisons between theory and experiment much more feasible.

A Broader View of Self-Assembly

At a deeper level, the study reshapes how scientists think about self-assembly under force and flow. It demonstrates that complex structures do not always require precise control or external manipulation. Sometimes, simple physical principles, acting together, are enough to generate remarkable complexity.

By revealing how hydrodynamics, gravity, and thermal motion interact to produce knots, the research adds a new chapter to our understanding of soft-matter systems and opens doors to future discoveries.

Research Paper Reference

Hierarchical Knot Formation of Semiflexible Filaments Driven by Hydrodynamics

Physical Review Letters (2025)

https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/z7jb-fvjl