Scientists Have Finally Figured Out How Materials Hotter Than the Sun’s Surface Conduct Electricity

Understanding how electricity flows through everyday materials like metals is something physics has handled pretty well for decades. But push those materials into extreme temperatures and pressures, and the rules start to blur. That’s exactly the challenge scientists face when studying warm dense matter, a strange and poorly understood state of matter that exists inside stars, planets, and fusion experiments. Now, after nearly a decade of work, researchers at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have developed a new way to directly measure how electricity behaves in materials heated to temperatures hotter than the surface of the Sun—and the results are both surprising and important.

Warm dense matter forms under conditions where solids are heated so intensely that they begin to behave like plasmas, but without fully losing their dense, solid-like structure. These conditions are found in the cores of stars, inside giant planets, deep within Earth’s interior, and during nuclear fusion experiments. Despite being widespread across the universe, warm dense matter remains one of the hardest states of matter to describe accurately.

One of the biggest missing pieces has been electrical conductivity. Knowing how well electricity flows through warm dense matter is crucial for improving models of planetary interiors, understanding how Earth’s magnetic field is generated, and refining simulations used in fusion energy research. The problem is that traditional conductivity measurements require physical contact with a material—something that becomes impossible when the material is glowing at tens of thousands of degrees.

Why Measuring Conductivity in Extreme Matter Is So Difficult

In normal laboratory conditions, measuring electrical conductivity is straightforward. You attach electrodes, apply a voltage, and measure the current. But warm dense matter is anything but normal. At temperatures approaching 10,000 Kelvin, materials vaporize, melt, and violently rearrange at the atomic level. Any physical probe would instantly disintegrate.

Because of this, scientists have long relied on indirect estimates, using theoretical models and simulations rather than real measurements. That approach has left major uncertainties. Without experimental data, physicists have struggled to confirm whether their models actually reflect what’s happening inside stars or planets.

This uncertainty is what motivated Ben Ofori-Okai and his team at SLAC to find a completely new way to tackle the problem—one that doesn’t require touching the material at all.

A New Contactless Technique Using Light

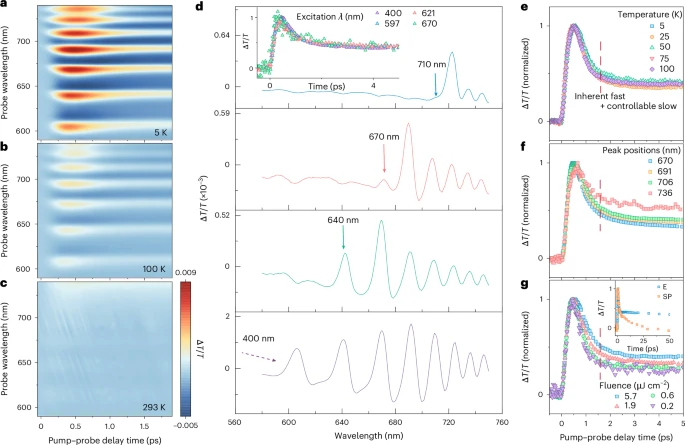

The breakthrough came from combining terahertz spectroscopy with ultrafast electron diffraction, two advanced techniques that allow scientists to probe matter using light and electrons instead of physical contacts.

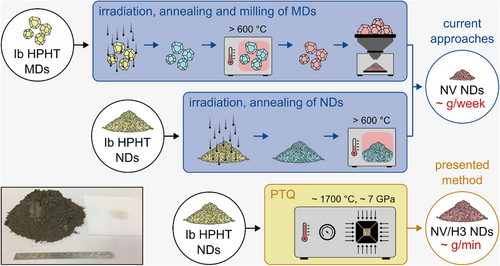

In the experiment, researchers started with a thin sheet of aluminum, chosen because its properties are well understood under normal conditions. A powerful laser rapidly heated the aluminum to about 10,000 Kelvin (17,540°F)—nearly twice as hot as the surface of the Sun—forcing it into a warm dense matter state.

Once the aluminum reached this extreme condition, the team fired a pulse of terahertz-frequency light at it. Terahertz radiation sits between microwaves and infrared light on the electromagnetic spectrum and has wavelengths small enough to interact directly with electrons inside a material.

This light induced an electric field within the molten aluminum. By carefully measuring how the terahertz pulse changed as it passed through the material, the researchers could directly calculate the electrical conductivity—all without physical contact.

According to the team, this is now the most accurate method ever developed for measuring electrical conductivity in warm dense matter.

A Surprising Drop in Conductivity

What the researchers observed next caught them off guard.

As the aluminum heated up, its electrical conductivity dropped—not once, but twice.

The first drop happened when the aluminum transitioned from a solid into warm dense matter. This was expected. As atoms gain energy and move more freely, electrons scatter more often, reducing conductivity.

The second drop, however, was completely unexpected.

To understand what caused it, the team turned to one of SLAC’s most powerful tools: the Megaelectron-Volt Ultrafast Electron Diffraction (MeV-UED) instrument at the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS). This facility allows scientists to send high-energy electron beams through a material and capture atomic-scale snapshots in less than a trillionth of a second.

Using MeV-UED, the researchers watched how the aluminum’s atomic structure evolved during heating. They discovered that the second conductivity drop coincided with a rapid shift from a more ordered atomic arrangement to a highly disordered one. This structural change dramatically affected how electrons moved through the material.

In other words, it wasn’t just temperature that mattered—atomic structure played a critical role in determining conductivity.

Why This Discovery Matters

This finding has major implications for physics. Many existing models of warm dense matter assume that conductivity changes smoothly with temperature. The discovery that structural transitions can cause sudden drops means those models may be missing key physics.

By providing direct, high-precision data, this new technique gives theorists something they’ve lacked for years: reliable benchmarks. With better data, simulations of planetary interiors, stellar evolution, and fusion plasmas can become significantly more accurate.

The work also highlights the importance of having facilities capable of observing ultrafast processes, since many of these changes happen on timescales far too short for conventional instruments to detect.

What Is Warm Dense Matter, Exactly?

Warm dense matter sits in an unusual middle ground between solids, liquids, and plasmas. In this state:

- Temperatures range from thousands to millions of kelvin

- Densities remain close to those of solids

- Electrons and ions interact strongly

- Classical plasma physics and solid-state physics both fail

This makes warm dense matter incredibly challenging to model, but also incredibly important. It exists in environments where much of the universe’s mass resides, including planetary cores and stellar interiors.

Connections to Earth and Fusion Energy

Warm dense matter isn’t just an abstract astrophysical concept. It plays a role in the generation of Earth’s magnetic field, which is driven by the movement of electrically conductive material deep inside the planet. Understanding conductivity under extreme conditions helps scientists better model these processes.

It’s also highly relevant to inertial confinement fusion, where tiny fuel capsules are compressed and heated to extreme states in hopes of achieving sustainable fusion reactions. Materials like tungsten, used as dopants in fusion capsules, also pass through warm dense matter states during experiments.

What Comes Next

The team plans to apply this contactless conductivity measurement technique to other materials, including copper, tungsten, and eventually iron—a key component of Earth’s core. Studying more complex materials will help scientists understand how universal these conductivity behaviors are and whether similar structural effects appear elsewhere.

By extending these measurements, researchers hope to build a much clearer picture of how matter behaves under some of the most extreme conditions nature can produce.

Research Reference

Unveiling structural effects on the DC conductivity of warm dense matter via terahertz spectroscopy and ultrafast electron diffraction

Nature Communications (2025)

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-65559-5