Scientists Learn How to Precisely Create and Place Single-Photon Sources at the Atomic Scale Inside 2D Materials

Researchers have achieved a major breakthrough in quantum materials science by learning how to design, locate, and create single-photon sources at the atomic level inside ultrathin two-dimensional materials. This advance directly addresses one of the most persistent challenges in quantum technology: controlling where and how individual photons are produced inside a solid material.

Single-photon sources, also known as quantum emitters, are tiny defects in a material’s atomic structure that can emit exactly one photon at a time. These controlled bursts of light are a foundational building block for quantum computing, quantum communication, and ultra-precise sensing technologies. Until now, scientists have struggled to precisely identify the atomic structures responsible for this light emission and to engineer them in a predictable way.

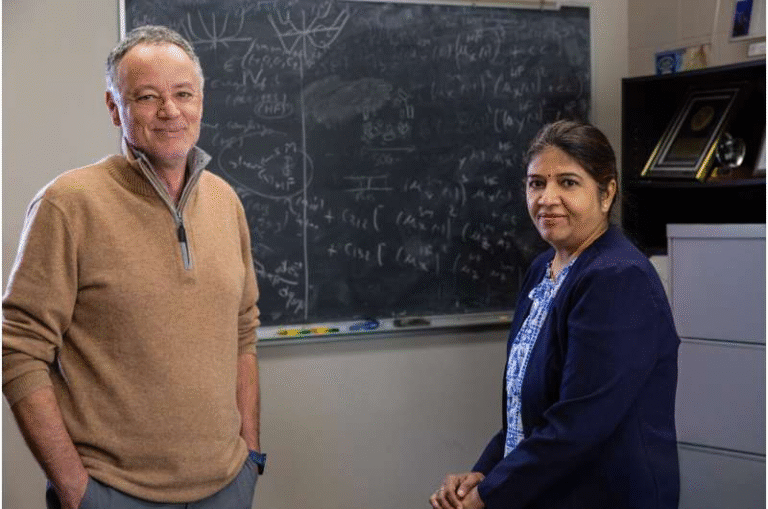

The new research, conducted by scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Argonne National Laboratory and the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, shows that it is now possible not only to observe these quantum emitters with extraordinary precision but also to create them intentionally at chosen locations. The findings were published in the journal Advanced Materials.

Why Quantum Emitters Matter So Much

Quantum emitters act like perfectly controlled on-off switches for light, releasing photons one at a time instead of in large, uncontrolled bursts. This single-photon behavior is essential for technologies such as quantum encryption, where information security relies on the fact that individual photons cannot be copied or intercepted without detection.

In quantum computing, photons generated by quantum emitters can be used to transmit information between quantum bits, or qubits, while quantum sensors rely on their extreme sensitivity to detect tiny changes in the environment. The problem has never been understanding why these emitters are important. The problem has been finding them, understanding them, and controlling them at the scale of individual atoms.

The Material at the Center of the Discovery

The research focused on hexagonal boron nitride, often shortened to hBN. This is a two-dimensional material, meaning it is only a few atoms thick, similar in structure to graphene. Hexagonal boron nitride is already known for hosting stable quantum emitters, even at room temperature, making it an attractive candidate for real-world quantum devices.

However, because these emitters are formed by tiny defects in the atomic lattice, identifying their exact structure has been extremely difficult. Studying light emission usually requires thicker samples, while studying atomic structure requires thinner ones. This fundamental tradeoff has long prevented scientists from seeing both properties at once.

A Custom Microscope Changes Everything

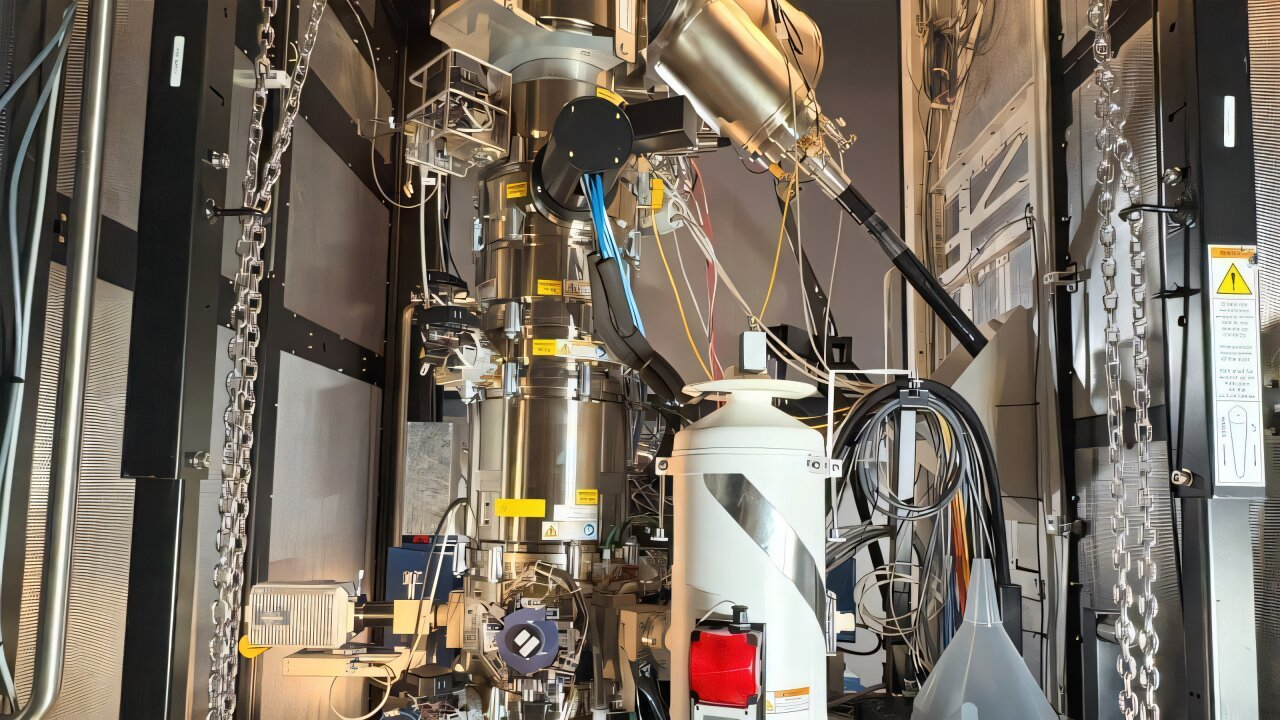

To overcome this limitation, the team used a highly specialized instrument called QuEEN-M, short for Quantum Emitter Electron Nanomaterial Microscope. Located at Argonne’s Center for Nanoscale Materials, QuEEN-M is designed specifically to study quantum emitters at extremely high resolution.

The microscope combines advanced electron optics with cathodoluminescence spectroscopy, a technique where a focused electron beam excites a material and causes it to emit light. By analyzing the color and intensity of that emitted light, researchers can learn detailed information about the defects responsible for photon emission.

This setup allowed the team to simultaneously observe atomic-scale structure and optical behavior, something that had previously been out of reach.

Twisting Layers to Amplify Light

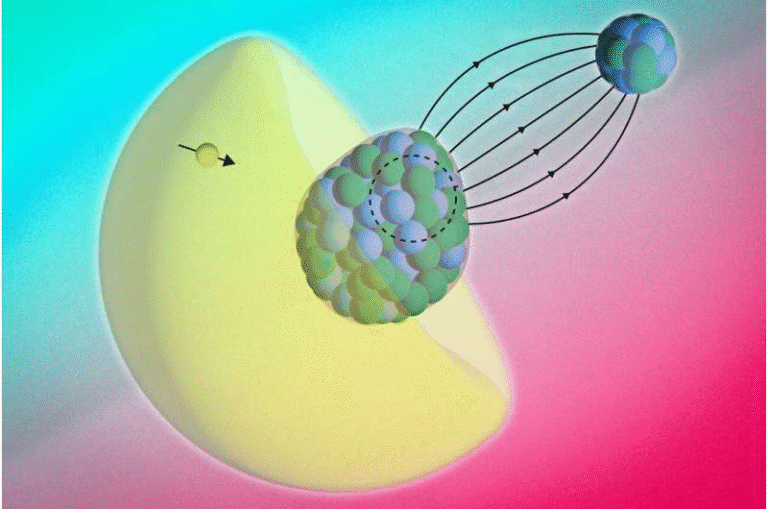

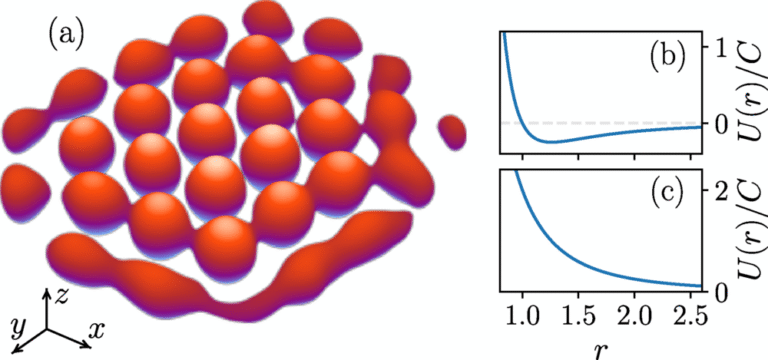

One of the most important discoveries came from studying twisted interfaces in hexagonal boron nitride. By stacking layers of hBN and rotating them at specific angles, the researchers found that the light emitted by quantum emitters became dramatically stronger.

In some cases, the signal intensity increased by as much as 120 times. This boost in brightness made it possible to pinpoint the location of individual quantum emitters with astonishing accuracy, down to less than 10 nanometers. That level of precision is critical for placing emitters exactly where they are needed in future quantum devices.

Identifying the Atomic Structure of a Quantum Emitter

With this enhanced signal, the team was able to make one of the most important advances of the study: identifying the exact atomic structure responsible for a specific quantum emitter.

They found that a blue-emitting quantum emitter in hexagonal boron nitride is formed by a carbon dimer, meaning two carbon atoms stacked vertically within the hBN lattice. This direct link between atomic structure and optical emission had been theorized before but never demonstrated so clearly.

Understanding this structure finally answers a long-standing question about what actually creates certain quantum emitters in hBN.

Creating Quantum Emitters on Demand

Perhaps the most impressive part of the research is that the scientists did not stop at identification. They demonstrated that they could engineer these quantum emitters intentionally.

By introducing carbon into the material and using the focused electron beam from the microscope, the team was able to activate quantum emitters exactly where they wanted them. This shows that quantum emitters are no longer random imperfections but can be designed, placed, and tuned on demand.

This level of control represents a major step toward scalable quantum technologies.

Why Precise Placement Is Critical

For quantum devices to work efficiently, photon sources must be positioned with high spatial accuracy. Emitters need to align with optical cavities, waveguides, or electronic components on a chip. Random placement makes it extremely difficult to integrate quantum materials into functional devices.

This research demonstrates a clear path toward custom-built quantum materials, where emitters are placed exactly where they are needed to maximize performance and efficiency.

How This Advances Quantum Technology

By linking atomic structure to light emission and showing how to engineer that structure deliberately, the study opens the door to next-generation quantum hardware. Materials can now be designed with specific quantum properties, optimized for computing, communication, or sensing applications.

It also highlights the importance of advanced research infrastructure. Instruments like QuEEN-M make it possible to explore phenomena that simply cannot be seen with conventional microscopes.

Additional Background on 2D Materials and Quantum Emitters

Two-dimensional materials have become a major focus of quantum research because they offer clean, well-defined atomic environments. Their thinness allows defects to strongly interact with light, making them ideal hosts for quantum emitters.

Hexagonal boron nitride stands out because its emitters are stable and operate at room temperature, unlike many quantum systems that require extreme cooling. This makes hBN particularly promising for real-world quantum devices, not just laboratory demonstrations.

The ability to engineer atomic defects in such materials could also inspire new approaches to quantum photonics, where light and matter are integrated on the same chip.

Looking Ahead

This research marks a turning point in quantum emitter engineering. Instead of searching for naturally occurring defects, scientists can now build them with intention and precision. That shift brings quantum technologies closer to practical deployment and large-scale manufacturing.

As techniques like this continue to improve, the dream of reliable, chip-based quantum devices becomes far more realistic.

Research paper:

Hanyu Hou et al., Nanometer Resolution Structure-Emission Correlation of Individual Quantum Emitters via Enhanced Cathodoluminescence in Twisted Hexagonal Boron Nitride, Advanced Materials (2025).

https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202501611