Ultrafast Electron Diffraction Reveals How Light Makes Atomic Layers Twist in Moiré Materials

Researchers from Cornell University and Stanford University have captured something scientists have long suspected but never directly seen: atomically thin layers in moiré materials physically twisting in response to light. Using a powerful method called ultrafast electron diffraction, the team recorded a rapid twist-and-untwist motion unfolding within a trillionth of a second. Their findings, published in Nature, open the door to understanding and potentially controlling the behavior of these unusual materials in real time.

What the Researchers Observed

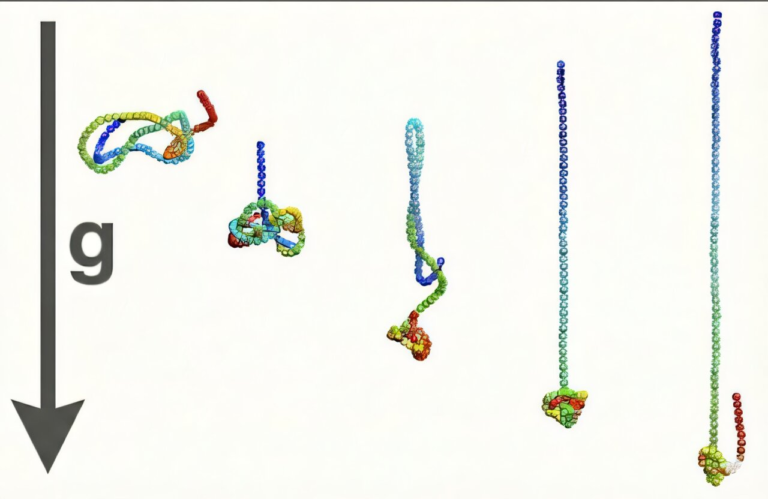

When a carefully timed pulse of light hit a crystalline sheet only a few atoms thick, the atoms didn’t simply vibrate randomly. Instead, the layers performed a coordinated, rhythmic twisting motion. This motion was extremely brief, occurring on the picosecond scale, and had never been directly observed before in moiré systems.

The research team discovered that within about 1 picosecond, the moiré diffraction signal intensified — meaning the layers twisted more tightly. A few picoseconds later, the signal weakened, showing the structure springing back. The twist angle change, according to data analysis and modeling, had a peak-to-trough magnitude of roughly 0.6 degrees, driven by a coherent torsional oscillation with sub-terahertz frequency.

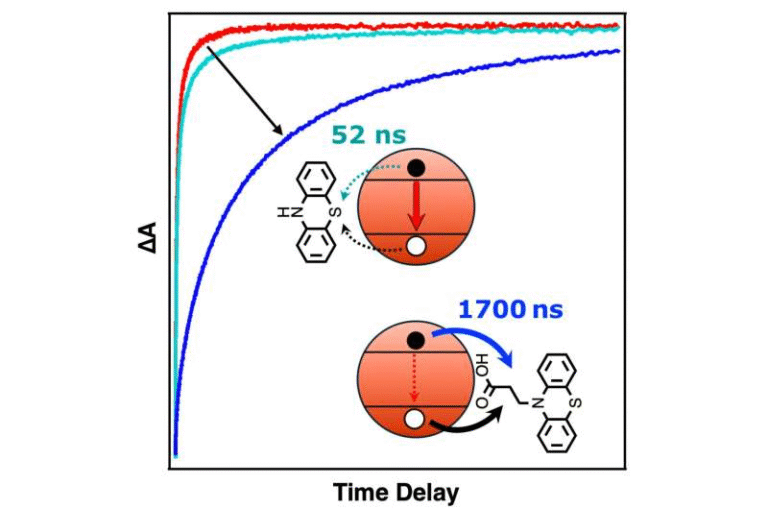

This dynamic structural response was triggered by ultrafast charge transfer between the layers when they were struck by above-band-gap light. The influx of charge momentarily strengthened interlayer attraction, causing the layers to pull tighter before relaxing again.

How They Captured This Ultrafast Motion

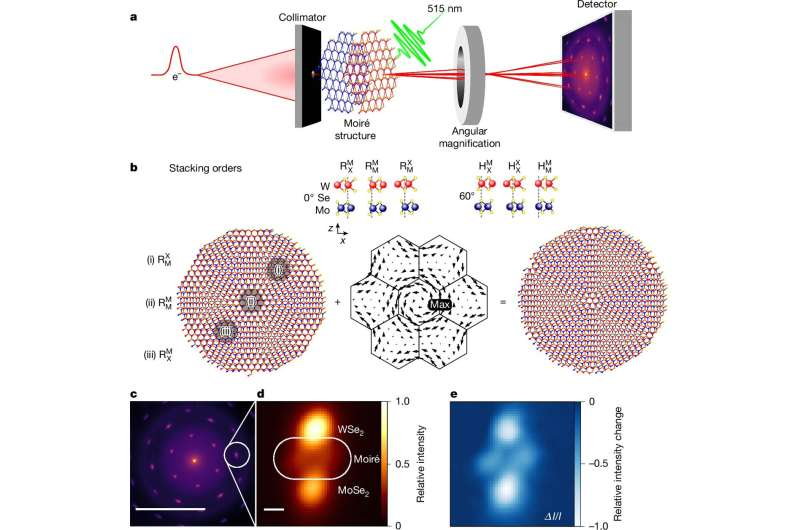

To record such rapid atomic movement, the researchers used a pump-and-probe technique. A laser pulse (the pump) excited the sample, and an ultrafast electron pulse (the probe) generated a diffraction pattern revealing how the atoms shifted over time.

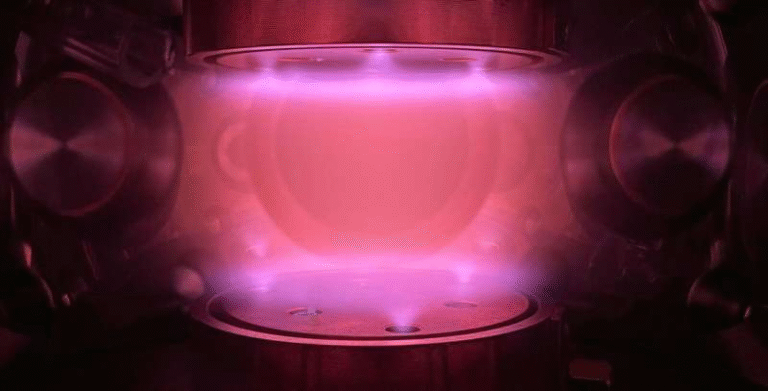

This was possible only because of a custom-built ultrafast electron diffraction instrument developed at Cornell. The setup included an advanced detector — the Electron Microscope Pixel Array Detector (EMPAD) — known for its exceptional sensitivity. Although EMPAD was originally designed for still imaging, it was adapted here to act like a high-speed atomic-scale movie camera. Most detectors would have blurred out the tiny signals the team was looking for, but EMPAD’s precision allowed them to see subtle changes in the moiré diffraction peaks clearly.

The moiré samples used in the experiment were prepared at Stanford using WSe₂ and MoSe₂ bilayers stacked with twist angles of 2 degrees and 57 degrees. These carefully engineered materials were essential because the moiré pattern itself depends entirely on how two layers are twisted relative to each other.

Why This Discovery Matters

For years, researchers working on moiré materials — the foundation of the field known as twistronics — have believed that once you stack the layers at a specific twist angle, the structure stays fixed. The electronic properties may change depending on the angle, but the geometry itself was assumed to be stable.

This study overturned that assumption. It showed that not only can the layers move, but they can do so in a coherent, collective way when stimulated by light.

This has major implications. The twist angle strongly influences properties such as superconductivity, magnetism, correlated insulating behavior, and quantum electronic effects. If light can dynamically modulate the twist angle, even by a fraction of a degree, it could allow scientists to tune these properties on demand and on ultrafast timescales.

This opens up possibilities for future technologies where materials change their electronic or quantum behavior instantaneously in response to precisely tailored light pulses.

The Collaborative Effort Behind the Research

The project relied on a close collaboration between Cornell’s and Stanford’s research groups. Cornell provided the custom-built ultrafast electron diffraction instrument and detector system, while Stanford provided the high-quality moiré samples. The experiment required extremely fine-tuned hardware modifications, and the data analysis involved reconstructing the complex atomic motions hidden within the diffraction patterns.

Key contributors included researchers who developed the instrument, the detector, the moiré samples, and the data interpretation framework. Their combined expertise allowed them to observe moiré-pattern motion that would otherwise be invisible.

What Comes Next

Stanford’s materials lab has already developed new moiré samples specifically designed to push the Cornell instrument to its limits. The next round of experiments will investigate how various materials and twist angles respond to light, and whether other dynamic behaviors — beyond twisting — might occur.

Ultimately, the team aims to understand how to use light to actively control quantum behaviors in real time. This could include real-time tuning of superconductivity strength, switching between magnetic and nonmagnetic phases, or manipulating exotic electron behaviors unique to 2D materials.

Additional Background: What Are Moiré Materials?

Moiré materials are created by stacking two extremely thin layers (such as graphene or transition metal dichalcogenides) with a slight rotational mismatch. This generates a large-scale interference pattern called a moiré superlattice, which profoundly alters how electrons move through the material.

A tiny change in twist angle — even a fraction of a degree — can lead to dramatically different behaviors. For example:

- Certain twist angles cause electrons to strongly interact, producing correlated insulating phases.

- Other angles create conditions for unconventional superconductivity.

- Moiré materials can host flat electronic bands, where electrons behave differently than in normal solids.

- They can form quantum phases of matter not seen in untwisted layers.

Because of this extreme sensitivity, controlling twist angle has become one of the most promising ways to engineer new quantum materials.

Additional Background: What Is Ultrafast Electron Diffraction?

Ultrafast electron diffraction (UED) is a technique used to observe how atoms move within materials on extremely short timescales. It works by firing very short pulses of electrons at a sample. These electrons diffract off the material’s atomic structure, forming a pattern that reveals how atoms are arranged.

By timing these pulses precisely after a laser excitation, researchers can construct a frame-by-frame view of how the material’s structure changes — effectively creating a movie of atoms moving on femtosecond or picosecond timescales.

UED is especially powerful for studying:

- Phase transitions

- Lattice vibrations

- Structural changes triggered by light

- Ultrafast motions in low-dimensional materials

The experiment described in this study represents one of the clearest demonstrations of UED capturing a torsional moiré phonon — a twisting structural mode unique to moiré systems.

Research Paper Reference

Photoinduced Twist and Untwist of Moiré Superlattices – Nature (2025)