Why Scientists Are Seriously Talking About an Antimatter Manhattan Project for Deep Space Travel

Chemical rockets have done an incredible job of getting humanity off Earth. They took us to the Moon, built space stations, and now power reusable spacecraft like SpaceX’s Starship, which can move enormous payloads around the solar system. But when it comes to traveling far beyond our cosmic neighborhood, especially to nearby stars, chemical propulsion quickly runs into hard physical limits. No matter how refined rocket engines become, they simply cannot deliver the energy required to reach a significant fraction of the speed of light.

That is where antimatter enters the conversation.

A growing number of physicists and aerospace thinkers are now making the case for what has been provocatively dubbed an “antimatter Manhattan project”—a large, coordinated research effort aimed at turning antimatter propulsion from a theoretical idea into usable technology for deep-space missions. The argument is not that antimatter travel is easy or imminent, but that the physics already points clearly in this direction, and incremental progress could unlock extraordinary capabilities.

Why Antimatter Is So Powerful

Antimatter stands apart from every other known energy source because of how completely it converts mass into energy. When antimatter comes into contact with ordinary matter, the two annihilate each other entirely. Unlike chemical reactions, which rearrange atoms, or nuclear reactions, which split or fuse nuclei, antimatter annihilation converts 100% of the mass involved directly into energy.

This process follows Einstein’s famous equation E = mc², and the squared speed of light term makes all the difference. The result is an energy density roughly 1,000 times greater than nuclear fission, which is currently the most energy-dense technology used in practical systems.

In propulsion terms, this means antimatter has the theoretical potential to accelerate spacecraft to tens of percent of light speed, opening the door to interstellar missions that would otherwise take centuries or millennia.

From Theory to Hardware: The Three Big Challenges

While the physics of antimatter is well understood, turning it into a usable propulsion system is an entirely different challenge. Researchers generally agree that progress depends on overcoming three major obstacles: production, storage, and engine design.

The Antimatter Production Problem

Today, antimatter is produced in extremely small quantities at specialized facilities such as CERN, where high-energy particle accelerators create antiprotons as a byproduct of particle collisions. Even with modern technology, production rates remain painfully low—measured in thousands of atoms per day, not grams.

The efficiency is another major issue. Current production methods convert only about 0.000001% of input energy into usable antimatter. That makes antimatter absurdly expensive in energy terms, far beyond any practical application for propulsion.

However, there is cautious optimism. Recent experimental advances have demonstrated eightfold improvements in production efficiency, which may not sound dramatic but represent an important trend. Historically, similar exponential gains transformed early nuclear research into the atomic energy industry in just a few decades.

Advocates of an antimatter development program argue that a few more breakthroughs of comparable scale could make antimatter production feasible for deep-space missions, where even tiny amounts of additional velocity can be invaluable.

The Even Harder Problem of Storage

Producing antimatter is only half the battle. Storing it safely is arguably the greater challenge.

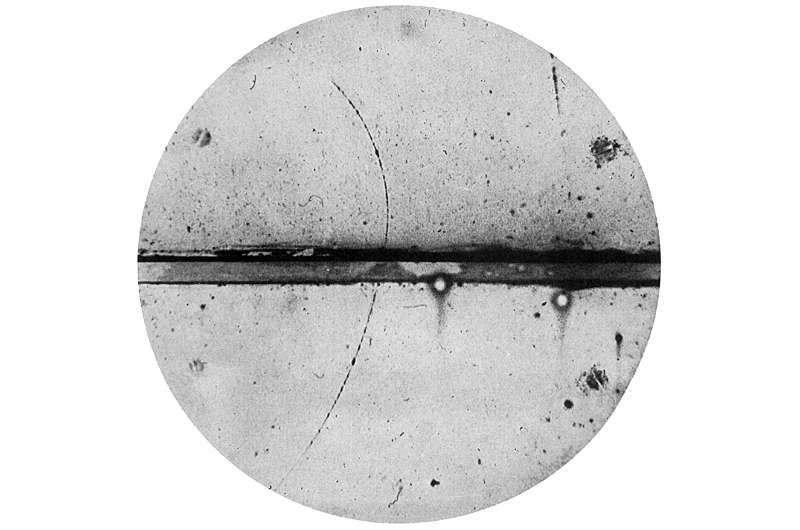

Antimatter cannot touch the walls of any container made of ordinary matter without instantly annihilating. Current experiments rely on electromagnetic traps, which suspend charged antimatter particles in a vacuum using carefully shaped magnetic fields. These systems work, but they are large, fragile, power-hungry, and extremely complex.

One promising idea involves converting antimatter into antihydrogen, a neutral atom composed of an antiproton and a positron. In theory, antihydrogen could be stored as a tiny droplet or crystal inside a cryogenically cooled vacuum chamber, held in place using finely tuned electrostatic fields.

This concept resembles techniques already used in advanced physics experiments and even shares similarities with technologies developed for quantum computing. Crucially, such storage systems could be tested safely using ordinary hydrogen by simply reversing the electric charges, allowing engineers to refine designs without handling dangerous materials.

Designing an Engine That Can Use Antimatter

Even if production and storage are solved, antimatter must still be converted into useful thrust. Several propulsion concepts have been proposed, ranging from relatively simple to highly sophisticated.

One of the simplest designs uses antimatter annihilation to heat a solid block of material, through which propellant flows. This approach resembles a nuclear thermal rocket but avoids the need for a heavy onboard nuclear reactor. Performance would likely exceed chemical rockets and rival nuclear propulsion systems.

More advanced designs involve combining antimatter with uranium-238, the most common naturally occurring form of uranium. When antiprotons strike U-238 nuclei, they can trigger fission reactions that release streams of highly charged particles. These particles deposit energy far more efficiently into exhaust propellant than gamma rays alone, resulting in significantly higher thrust efficiency.

Depending on configuration, such engines could operate across a wide range of performance levels, from conventional interplanetary travel to missions capable of interstellar velocities.

Surprisingly Small Fuel Requirements

One of the most striking aspects of antimatter propulsion is how little fuel is theoretically required. Detailed estimates suggest that a round-trip mission to Pluto in under 20 years could be achieved using about 45 grams of antimatter combined with roughly 10 kilograms of uranium-238.

Together, these materials would occupy only about 500 cubic centimeters, roughly the volume of a small bottle. Compared to the massive fuel tanks required for chemical rockets, the difference is staggering.

With chemical propulsion already approaching maturity thanks to reusable launch systems, proponents argue that antimatter represents a logical next frontier rather than a speculative fantasy.

Additional Context: Antimatter Research Today

Antimatter is not just a propulsion curiosity. It is a major focus of fundamental physics research, particularly at CERN’s Antimatter Decelerator and ELENA facilities. Experiments such as ALPHA and AEgIS study the properties of antimatter, including how it behaves under gravity and how long it can be trapped in stable configurations.

These experiments are essential groundwork for any future engineering applications. Understanding how antimatter responds to electromagnetic fields, temperature changes, and gravitational forces directly informs storage and propulsion concepts.

Historically, antimatter propulsion ideas are not new. Concepts like ICAN-II, AIMStar, and antimatter-catalyzed nuclear pulse engines were explored as early as the 1980s and 1990s. What has changed is the steady improvement in particle physics technology and the growing urgency of long-term space exploration goals.

Why a Manhattan Project–Scale Effort Is Being Discussed

The comparison to the Manhattan Project is intentionally provocative. It does not imply weaponization, but rather emphasizes the scale, coordination, and urgency that would be required to make antimatter propulsion real.

Advocates argue that waiting for incremental, underfunded progress could delay breakthroughs for centuries, while a focused international effort might compress development timelines dramatically. Whether such an initiative is politically or economically realistic remains an open question.

What is clear is that antimatter is no longer confined to science fiction. It is a scientifically grounded, deeply challenging, and potentially transformative technology that could redefine how humanity explores the universe.

Research reference:

Casey Handmer, Antimatter Development Program and Propulsion Feasibility Analysis

https://caseyhandmer.wordpress.com/2025/11/26/antimatter-development-program/