X-Ray Laser Experiments Reveal the Hidden Atomic Structure of Water’s Surface

Water covers most of our planet and is essential to life, yet one of its most important regions—the thin surface layer where water meets air—has remained surprisingly mysterious. Scientists have now taken a major step toward understanding this elusive boundary, thanks to advanced X-ray laser experiments carried out at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in the United States. Using cutting-edge tools and techniques, researchers have directly observed how atoms and molecules behave at the surface of liquid water, confirming long-standing theories and opening new doors for studying chemistry at interfaces.

Why the Surface of Water Matters So Much

The surface of water is only a few atomic layers thick, but it plays an outsized role in natural and chemical processes. This is the zone where oceans exchange gases like carbon dioxide with the atmosphere, where clouds begin to form, and where countless chemical reactions take place. Despite being the most visible part of water—found on waves, droplets, puddles, and ponds—it is also one of the hardest to study.

The challenge lies in the sheer number of atoms in liquid water. When scientists try to probe the surface, signals from the bulk water beneath overwhelm the tiny contribution from the surface layer. Even when studying extremely small droplets, the interior still dominates most measurements. As a result, many ideas about water’s surface structure have relied on indirect evidence or theoretical models rather than direct observation.

A New Way to Isolate the Surface Signal

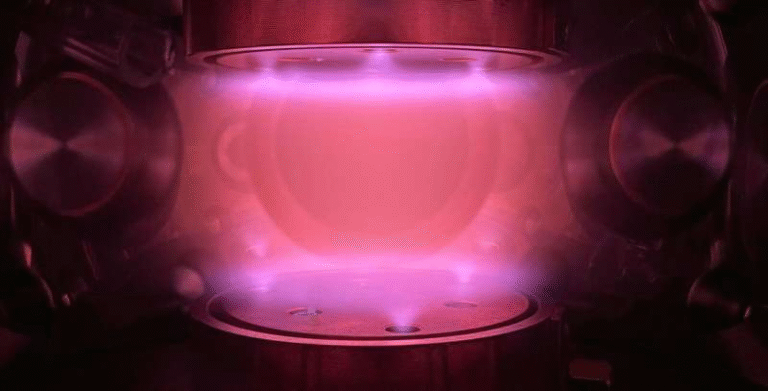

To overcome this problem, a research team led by scientists at SLAC developed an innovative experimental approach using the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), one of the world’s most powerful X-ray free-electron lasers. The key breakthrough was finding a way to collect clear X-ray data from the surface of water while minimizing interference from the bulk.

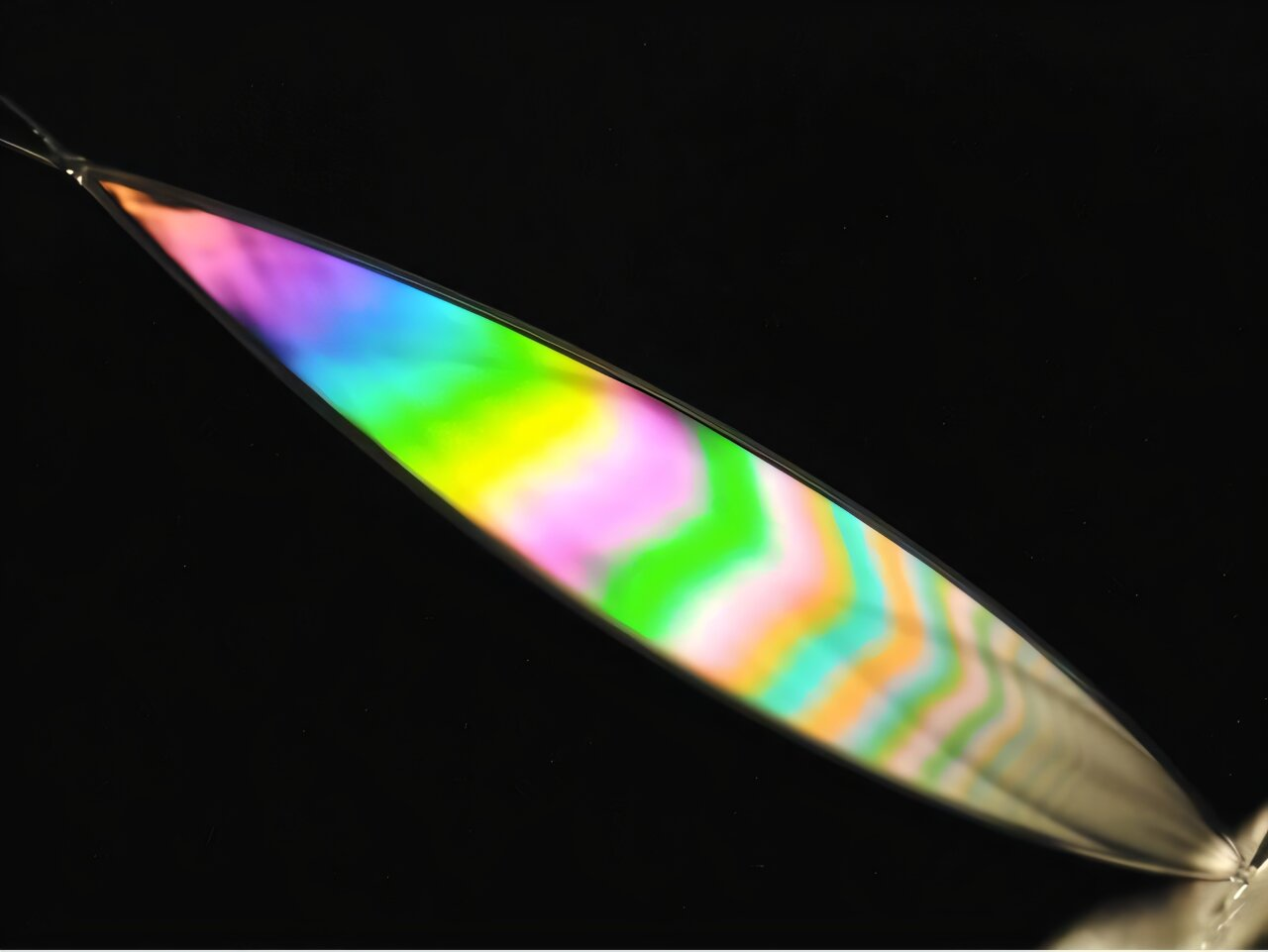

One crucial innovation involved how the water samples were delivered. Instead of using traditional cylindrical jets of liquid, the team employed ultra-thin, free-flowing sheets of water. These sheets are less than one micrometer thick—about 40 millionths of an inch—so thin that they shimmer like soap bubbles. This extreme thinness dramatically reduces the contribution from bulk water, making it possible to focus on surface effects that were previously hidden.

Harnessing the Power of the X-Ray Laser

Recent upgrades to the LCLS played a major role in making the experiments successful. The laser now delivers ultrashort pulses of X-rays—each lasting less than a millionth of a billionth of a second—with peak powers exceeding one terawatt. These pulses strike the water sheets at a rate of 120 times per second, providing both intensity and precision.

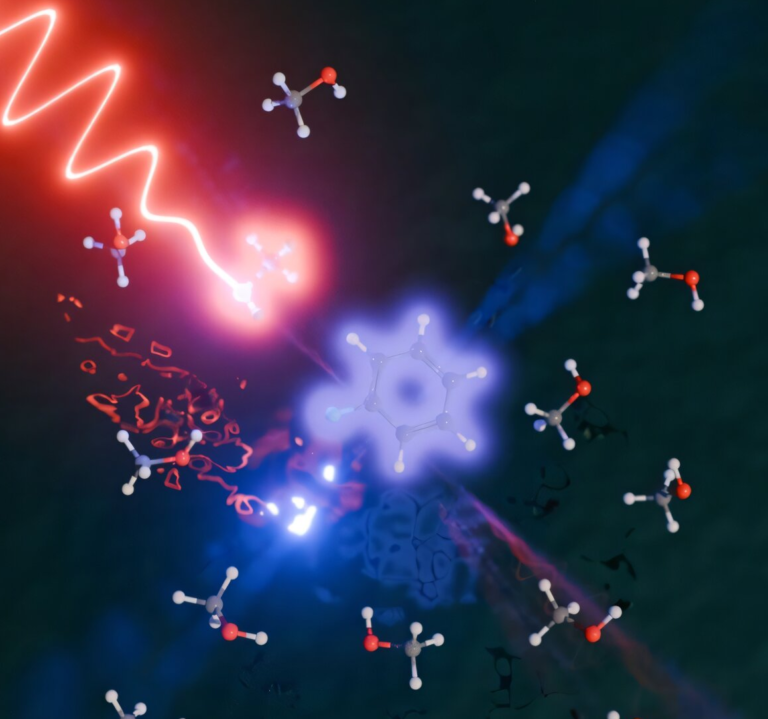

This immense power enables a nonlinear optical process known as second harmonic generation. In this process, two incoming photons combine to form a single outgoing photon with twice the energy. Importantly, this effect occurs only at interfaces where symmetry is broken—such as the boundary between water and air. That makes it an ideal tool for isolating signals from the surface alone.

The team tuned the laser to the soft X-ray region, which is particularly sensitive to oxygen atoms. This allowed them to track how oxygen participates in the hydrogen-bond network that gives water many of its unique properties.

What the Experiments Revealed About Water Molecules

Water molecules are famous for their ability to form hydrogen bonds. Each molecule can form up to four such bonds with its neighbors, creating a constantly shifting, three-dimensional network in the bulk liquid. This network is responsible for many of water’s unusual characteristics, including its high surface tension.

At the surface, however, the situation is very different. Molecules at the boundary cannot bond with air above them, so some of their atoms are left without partners. Earlier studies had already shown that hydrogen atoms often point outward into the air at the surface.

What had not been directly observed until now was the behavior of oxygen atoms. The new experiments provided clear evidence that oxygen atoms at the surface are also left partially unbonded and oriented toward the air. This confirms a long-suspected but unproven picture of water’s surface structure.

These findings show that water molecules at the surface interact with each other in fundamentally different ways than those in the bulk. The surface has its own distinct electronic and molecular structure, which helps explain why chemical reactions at interfaces can behave so differently from those in the interior of a liquid.

Why These Results Are So Important

Understanding the detailed structure of water’s surface has far-reaching implications. Many large-scale phenomena—such as how oceans absorb carbon dioxide or how atmospheric chemicals cycle—depend on reactions that happen at the air–water interface. The same is true for more applied fields, including electrochemistry, battery science, and the way soaps and detergents work.

By directly observing how atoms behave at the surface, scientists can now refine models of these processes and make more accurate predictions. The new technique also provides a powerful experimental benchmark for theoretical calculations, helping to bridge the gap between simulations and real-world behavior.

Beyond Pure Water: Exploring Other Interfaces

The researchers are not stopping with pure water. They have already adapted their setup to study interfaces between different liquids, such as oil and water. In earlier work, they created stacked layers of ultra-thin liquid sheets that flow continuously into the path of a laser beam, allowing them to probe liquid–liquid boundaries in real time.

Other experiments have examined how salts and dissolved ions behave at different interfaces, comparing their behavior at the water–air boundary with that at the water–oil boundary. These studies provide valuable insights into environmental chemistry and industrial processes where complex mixtures are involved.

Additional Background: Why Water Is So Unusual

Water’s behavior often defies intuition. Its unusually strong surface tension allows insects to walk across it and enables objects like razor blades to rest on its surface under the right conditions. These properties arise from the strength and flexibility of hydrogen bonding between molecules.

At the surface, the partial loss of these bonds creates a region that is both chemically active and structurally distinct. This makes the surface especially sensitive to external influences, such as pollutants, dissolved gases, or changes in temperature. Understanding this region at the atomic level is therefore essential for tackling a wide range of scientific and environmental challenges.

A New Window Into Liquid Interfaces

The combination of ultra-thin liquid sheets, high-power soft X-rays, and surface-specific nonlinear spectroscopy represents a first-of-its-kind experimental capability. Researchers believe it will have an immediate impact not only on water science but also on the study of liquids in general.

By finally making the invisible visible, these experiments provide a clearer picture of how molecules behave where liquids meet the world around them. It is a reminder that even something as familiar as water can still hold deep and fascinating secrets—waiting for the right tools to uncover them.

Research paper:

Hoffman, D. J. et al., Surface structure of water from soft X-ray second harmonic generation, Nature Communications (2025). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-65514-4