A 1990s Tomato Line Could Help Fight Today’s Billion-Dollar Virus Threat

A major plant disease is threatening tomato and pepper crops worldwide, and scientists may have found help in an unexpected place: a 30-year-old tomato line developed in the 1990s. Researchers from the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service (ARS), along with university collaborators, recently discovered that this forgotten line, known as tomatoNN, carries genetic resistance to the Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus (ToBRFV)—a fast-spreading and destructive pathogen capable of inflicting billions of dollars in losses.

What is ToBRFV and Why It Matters

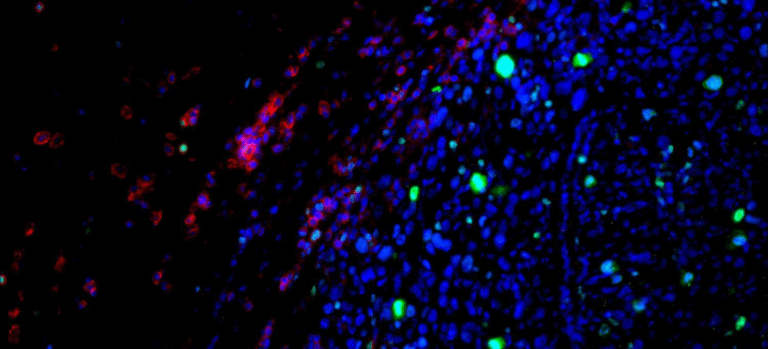

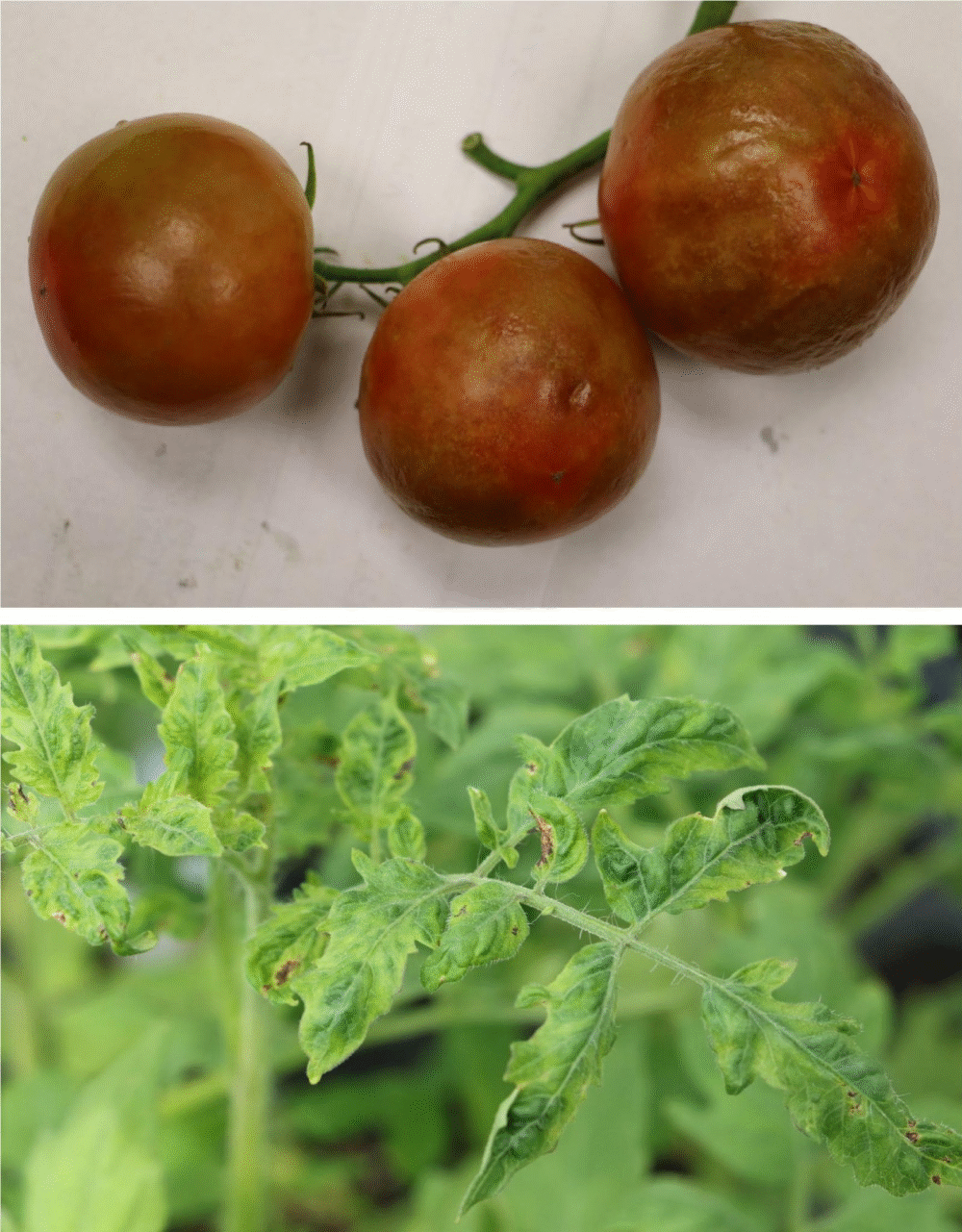

ToBRFV belongs to the tobamovirus family and is especially devastating because it overcomes resistance genes that protect today’s commercial tomato varieties. First detected in Jordan and Israel in 2015, it has since spread worldwide. Infected plants show leaf mosaic patterns, distortions, and brown wrinkled fruits that drastically reduce yields and market value.

The virus spreads quickly through contaminated seeds, tools, hands, clothing, or plant material. Once it enters a growing area, it can move fast, making prevention extremely difficult. Right now, growers depend on strict hygiene measures such as disinfecting equipment, sanitizing greenhouses, and keeping facilities clean. Products like Virkon S and Huwa-San disinfectants, along with heat treatments, are commonly used to suppress spread. But even with these steps, outbreaks remain a serious risk.

The Rediscovery of TomatoNN

The recent breakthrough comes from re-examining a line called tomatoNN, which was developed in the 1990s at ARS’s Plant Gene Expression Center in Albany, California. Back then, geneticist Barbara Baker and her colleagues inserted the N gene—originally isolated from a wild tobacco relative—into tomatoes. This N gene was known to give resistance against the Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV).

At the time, the tomatoNN line was notable for its TMV resistance, but its potential against other tobamoviruses wasn’t fully realized. Fast-forward three decades, and researchers led by Kai-Shu Ling at the U.S. Vegetable Laboratory in Charleston, South Carolina, decided to test it against ToBRFV.

Their results, published in Plant Biotechnology Journal (July 2, 2025), showed that tomatoNN plants displayed remarkable resistance. In lab conditions at 22°C (71.6°F), the plants were nearly immune: the virus could not spread systemically, symptoms were limited to local necrotic lesions on the leaves, and virus levels were extremely low to undetectable based on DAS-ELISA and RT-qPCR tests.

The Catch: Temperature Sensitivity

There is, however, a limitation. The resistance provided by the N gene in tomatoNN is temperature-sensitive. When plants were grown at 30°C (86°F), resistance weakened significantly—mirroring similar behavior seen with N-mediated TMV resistance.

This means the tomatoNN line works well under moderate conditions, but may fail in hotter climates or during heatwaves. Since temperature is a major factor in plant–pathogen interactions, further research is needed to understand how to stabilize resistance under higher temperatures.

What This Means for Growers

The discovery brings hope but also raises practical questions. For greenhouse growers, where temperatures can be managed more effectively, incorporating tomatoNN genes into commercial varieties could be a powerful tool. For open-field farmers, especially in warmer regions, resistance may not hold up.

Currently, the most reliable defense against ToBRFV remains prevention through hygiene. But adding genetic resistance into the mix could provide a much-needed safety net. Breeding programs are now considering tomatoNN as a foundation for new resistant cultivars.

Other Promising Genetic Leads

TomatoNN isn’t the only pathway. Separate studies in wild tomato species (Solanum pimpinellifolium) have identified QTLs (Quantitative Trait Loci) linked to resistance against ToBRFV. One major QTL was found on chromosome 11, with genes such as Solyc11g062150 (a TIR-NBS-LRR protein) and Solyc11g062180 (an LRR disease-resistance protein) emerging as potential candidates.

These discoveries could complement the tomatoNN approach, giving breeders multiple genetic strategies to tackle ToBRFV.

Looking Ahead

The rediscovery of tomatoNN shows how old genetic resources can become new solutions. While its temperature sensitivity limits its immediate use everywhere, it provides a valuable tool for greenhouse growers and a stepping stone for future breeding. Alongside strict sanitation practices and emerging QTL-based resistance, it could help secure one of the world’s most important crops.

TL;DR

A 1990s tomato line (tomatoNN) carrying the tobacco N gene has been found resistant to Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus (ToBRFV), a major global crop threat. Resistance is strong at 22°C but weakens at 30°C, making temperature a critical factor.

Research Paper: The N gene protects tomato plants from tomato brown rugose fruit virus infection – Plant Biotechnology Journal, July 2025