A New Dinosaur Species named Newtonsaurus Cambrensis from Wales Finally Identified After 125 Years

Paleontologists have confirmed the existence of a brand-new dinosaur species, named Newtonsaurus cambrensis, from a fossil that had been gathering dust for more than a century. This fossil, found in South Wales near Penarth in 1898–1899, was first described in 1899 by geologist Edwin Tully Newton, who gave it the name Zanclodon cambrensis. At the time, the classification was shaky because the genus Zanclodon had become a catch-all for a variety of early reptiles.

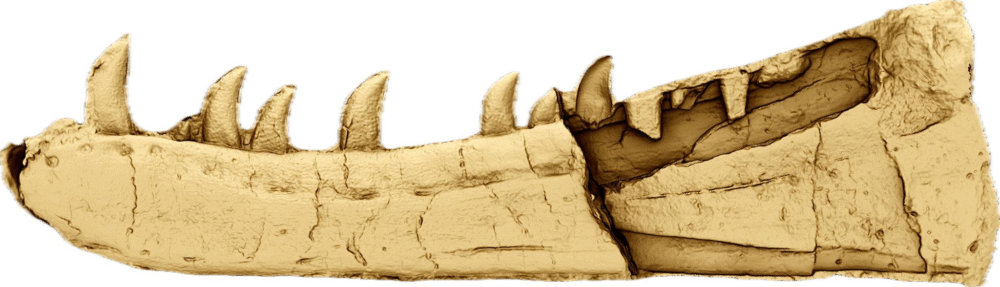

The specimen, recorded as GSM 6532, is a dentary—the front half of a lower jaw. What makes it even more remarkable is that the original bone material is gone. What survived are natural moulds preserved in rock, essentially negative impressions of the fossilized jaw. For over 125 years, scientists were not sure whether it belonged to a dinosaur at all.

This fossil sat in the collections of the National Museum of Wales (and its predecessor institutions) for decades, occasionally referenced in papers but never properly classified. Finally, in 2025, researchers at the University of Bristol, led by paleontology student Owain Evans with contributions from Cindy Howells, Nathan Wintle, and Professor Michael J. Benton, revisited the fossil with fresh eyes and modern technology.

Using Modern Digital Tools

Since the original bone was lost, the team had to rely on the rock moulds. They used photogrammetry—a method that stitches together multiple photographs to create detailed 3D digital models. By digitally inverting the moulds, they reconstructed a virtual model of the original jawbone.

The reconstructed jaw revealed impressive details: every ridge, groove, tooth socket, and even the serrations along the edges of the teeth were visible. Once both inner and outer moulds were fused into a complete 3D model, the anatomy could finally be studied as if the original bone were in hand.

This approach allowed the team to confirm that the fossil indeed belonged to a large theropod dinosaur—a two-legged, meat-eating predator from the Late Triassic period.

Why It’s Definitely a Dinosaur

The new analysis showed distinctive dinosaur features, especially in the way the teeth were implanted. The fossil’s traits place it firmly within Theropoda, the group that would later give rise to famous giants like Tyrannosaurus rex.

More specifically, Newtonsaurus seems to sit near the base of Neotheropoda, close to where the two major branches—Coelophysoidea and Averostra—diverged. This makes it an important species for understanding the early evolution of predatory dinosaurs.

Size and Scale

One of the most surprising aspects of Newtonsaurus cambrensis is its size. The preserved jaw fragment is 28 centimeters long, but this is only the front half. The complete dentary would have measured around 56–60 centimeters, nearly double that length.

From this, paleontologists estimate the dinosaur’s total body length at about 5 to 7 meters. That makes Newtonsaurus unusually large for a Triassic theropod. Most theropods from this time period were much smaller—often only half the size or less. This discovery suggests that large predatory dinosaurs appeared earlier in Europe than previously thought.

Geological Context

The fossil likely comes from the Cotham Member of the Lilstock Formation, part of the Penarth Group, which dates to the Rhaetian stage of the Late Triassic (roughly 202 million years ago).

This formation represents a marginal marine or coastal environment, with alternating terrestrial and shallow marine deposits. South Wales during this period would have been a shoreline environment, where early dinosaurs and other reptiles lived alongside fish, amphibians, and marine reptiles.

These Triassic beds in Wales are rare and scientifically valuable. They offer a glimpse into ecosystems that existed just before the Triassic–Jurassic boundary, a time of major evolutionary transitions when dinosaurs began to dominate terrestrial environments.

Naming the New Species

Since the genus name Zanclodon was long abandoned, the researchers decided to give the Welsh fossil a new identity. The genus name Newtonsaurus honors Edwin Tully Newton, the first to describe the specimen in 1899. The species name cambrensis comes from “Cambria,” the Latin word for Wales.

So, after more than a century of uncertainty, the fossil has a proper name: Newtonsaurus cambrensis.

Importance of Historical Specimens

This discovery highlights how valuable old museum collections can be. Fossils collected by Victorian geologists, even when fragmentary or poorly understood, often turn out to be far more significant once reanalyzed with modern tools.

The case of Newtonsaurus shows how technology like 3D scanning and digital modeling can breathe new life into specimens that were once thought too incomplete or ambiguous to be useful.

Broader Significance in Paleontology

The confirmation of Newtonsaurus cambrensis has several implications:

- It expands our knowledge of Triassic dinosaur diversity in Europe, showing that large theropods were present earlier than previously believed.

- It provides insight into the early stages of theropod evolution, sitting close to the origins of the two major theropod lineages.

- It demonstrates how re-examining historical fossils can lead to breakthroughs, even after more than 100 years.

- It highlights Wales as a significant region for paleontological research, with rare Triassic deposits that could hold more undiscovered species.

Additional Context: Triassic Theropods

To put Newtonsaurus into perspective, here’s some background on Triassic theropods:

- The Triassic period (252–201 million years ago) was the dawn of the dinosaurs. Early theropods were generally small, lightly built predators.

- Famous early theropods include Coelophysis (about 3 meters long) from North America and Liliensternus (about 5 meters long) from Germany.

- Compared to these, Newtonsaurus is exceptional because it reaches the upper size range for Triassic predators.

By the end of the Triassic, theropods had already started to diversify and spread across Pangaea. Discoveries like Newtonsaurus help fill the gaps in this evolutionary story.

Additional Context: The Importance of Photogrammetry

One of the most fascinating aspects of this study is the use of photogrammetry. This technique is becoming increasingly popular in paleontology because:

- It allows fossils to be studied in non-destructive ways, preserving fragile specimens.

- It creates high-resolution 3D models that can be shared digitally with researchers worldwide.

- It can reconstruct lost or incomplete fossils, especially when only moulds or impressions remain.

In the case of Newtonsaurus, photogrammetry was the only way to bring the fossil back to life, since no actual bone was preserved.

Wales and Its Fossil Record

Wales is not usually the first place people think of when it comes to dinosaur fossils. However, the country has a surprisingly rich geological history:

- Triassic and Jurassic rocks along the coastlines occasionally yield important vertebrate fossils.

- Fossil beds in South Wales are rare on a global scale but crucial for understanding European ecosystems at the end of the Triassic.

- The discovery of Newtonsaurus adds Wales to the growing list of locations where large Triassic dinosaurs have been confirmed.

This re-identification may also encourage more exploration of old collections in Welsh and UK museums. There could very well be other fossils waiting for a second look.

Conclusion

The discovery of Newtonsaurus cambrensis is not just about naming a new dinosaur. It’s about bringing a forgotten fossil back into the spotlight, showing the power of modern technology, and expanding our understanding of dinosaur evolution at a critical point in Earth’s history.

For over 125 years, a jawbone sat in a museum, unrecognized for what it truly was. Now, thanks to new digital techniques and a careful reanalysis, we know that it belonged to a giant predator from Triassic Wales. At 5–7 meters long, this dinosaur was far larger than its contemporaries, hinting at an early expansion of large carnivores just before the Jurassic takeover.

This case underscores an exciting truth in paleontology: sometimes the most important discoveries are already in our museums, waiting for someone to look again.

Research Reference:

Re-assessment of a large archosaur dentary from the Late Triassic of South Wales, United Kingdom (2025, Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association)