A Simple Electroplating Trick Could Bring Ultra-Precise Nuclear Clocks Into Everyday Technology

Scientists have taken a major step toward making nuclear clocks smaller, tougher, and far more practical—and they did it using a technique borrowed straight from the world of jewelry. A research team led by physicists at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) has shown that an old-fashioned electroplating method can dramatically simplify how thorium-based nuclear clocks are built, while using 1,000 times less radioactive material than previous approaches.

This new work builds directly on a historic breakthrough achieved last year, when researchers successfully used lasers to excite the nucleus of thorium-229, something scientists had been chasing for nearly five decades. Now, by replacing fragile custom-grown crystals with thorium electroplated onto steel, the team has found a way to make nuclear clocks more durable, compact, and potentially affordable, opening the door to real-world applications far beyond the lab.

Why Thorium-229 Matters for Timekeeping

Modern atomic clocks already underpin much of our daily technology, from GPS navigation and cell phone networks to financial systems and power grids. These clocks measure time using the energy transitions of electrons in atoms. Nuclear clocks, however, aim to go one level deeper.

Thorium-229 is special because it has a unique low-energy nuclear transition that can be excited using laser light. This allows scientists to treat the nucleus almost like an electron in an atom—something that is normally impossible because nuclear energy levels are far too high.

The advantage is huge. Nuclear transitions are far less sensitive to environmental disturbances such as temperature changes, electric fields, or magnetic noise. That means a nuclear clock could, in principle, be more accurate and more stable than even the best atomic clocks available today.

A Breakthrough Decades in the Making

The idea of a thorium nuclear clock has existed since the 1970s. In 2008, the UCLA-led team proposed a concrete plan: use a laser to excite thorium-229 nuclei and build a clock around that transition. But turning that idea into reality proved extraordinarily difficult.

Last year, after 15 years of work, the team finally succeeded. They embedded thorium-229 atoms into specially engineered fluoride crystals that could both stabilize the radioactive atoms and remain transparent to the laser light needed to excite the nucleus. This allowed them to observe the nuclear excitation directly, confirming that a nuclear clock was truly possible.

The achievement was widely recognized as a landmark moment in precision physics. However, it came with serious limitations.

The Thorium Supply Problem

Thorium-229 is extremely rare. It does not occur naturally in usable quantities and must be extracted from weapons-grade uranium. Worldwide, scientists estimate that only about 40 grams of thorium-229 exist for research purposes.

The crystal-based method required at least one milligram of thorium per experiment. While that may sound small, it represents a significant fraction of the global supply. The crystals themselves were also fragile, difficult to fabricate, and time-consuming to grow, making large-scale or commercial applications unrealistic.

Clearly, a better approach was needed.

Borrowing a Technique From Jewelry Making

The new study flips one long-held assumption on its head. Researchers had always believed that the material hosting thorium had to be transparent so the laser could reach the nuclei and the emitted photons could escape.

It turns out that assumption was wrong.

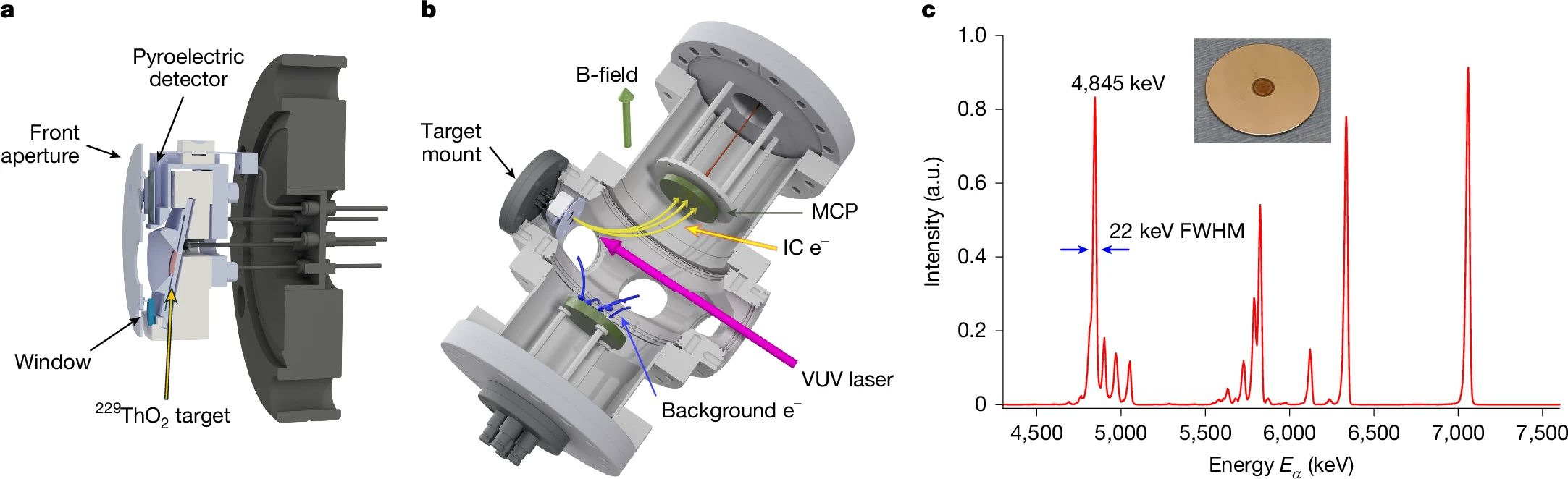

Instead of crystals, the team used electroplating, a process invented in the early 1800s and still widely used to coat jewelry with gold or silver. By slightly modifying this technique, they deposited an ultra-thin layer of thorium-229 oxide onto a piece of stainless steel.

Even though steel is opaque, the laser light can still penetrate just deep enough to excite thorium nuclei near the surface. But here’s the key difference: instead of emitting photons, the excited nuclei release electrons.

Those electrons create a measurable electric current.

Detecting an electrical signal is far simpler than detecting faint photons, and it allows the entire clock mechanism to be miniaturized. Most importantly, this method uses 1,000 times less thorium than the crystal approach.

Stronger, Simpler, and More Practical

The electroplated steel targets are not just easier to make—they are also much tougher than fragile crystals. The finished device is essentially a small, solid piece of metal, far better suited for real-world environments.

This discovery also dramatically shortens development time. What took 15 years of painstaking crystal engineering can now be achieved with a process that is simple, inexpensive, and well understood in industry.

Just as importantly, the researchers demonstrated for the first time that laser excitation of a thorium nucleus can be directly converted into an electrical signal, a crucial step toward building compact nuclear clocks.

What Nuclear Clocks Could Be Used For

The potential applications of thorium-based nuclear clocks are wide-ranging and significant.

One of the most pressing is GPS-independent navigation. Today’s navigation systems rely heavily on satellites, which are vulnerable to interference, cyberattacks, or solar storms. Highly accurate onboard clocks could allow aircraft, ships, submarines, and spacecraft to navigate without continuous satellite signals.

Submarines, for example, already use atomic clocks, but even small timing errors accumulate over time. Nuclear clocks could allow submarines to stay submerged far longer without surfacing to recalibrate.

In space exploration, ultra-stable clocks are essential for deep-space navigation, autonomous spacecraft, and eventually maintaining a solar-system-wide time standard for human settlements beyond Earth.

Closer to home, nuclear clocks could improve telecommunications, financial networks, radar systems, and power grid synchronization, all of which depend on precise timing.

A Tool for Fundamental Physics

Beyond technology, nuclear clocks are powerful scientific instruments. Their extreme stability makes them ideal for testing Einstein’s theory of relativity, searching for possible changes in fundamental constants, and probing new physics beyond current models.

Because nuclear transitions are so well shielded from external disturbances, any tiny deviation in their behavior could point to previously unknown physical effects, including potential interactions with dark matter.

Still Early, But a Clear Path Forward

While nuclear clocks are not about to replace atomic clocks overnight, this electroplating breakthrough removes several major barriers that have slowed progress for decades. By reducing material requirements, simplifying fabrication, and enabling electrical readout, the technology moves much closer to scalable, deployable systems.

What once seemed like an exotic laboratory curiosity is now beginning to look like a realistic candidate for next-generation timekeeping.

And perhaps the most surprising part of all is that the key innovation came not from advanced nanofabrication or exotic materials, but from one of the oldest industrial techniques still in use today.

Research paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09776-4