Bird-of-Paradise Feathers Inspire Scientists to Create the Darkest Fabric Ever Made

Researchers at Cornell University have developed what is now being described as the darkest fabric ever reported, drawing direct inspiration from the striking black feathers of a bird-of-paradise species known as the magnificent riflebird. This breakthrough combines biology, materials science, and textile design, resulting in a fabric that absorbs almost all incoming light while remaining wearable, flexible, and scalable for real-world use.

What “Ultrablack” Really Means

The term ultrablack is used for materials that reflect less than 0.5% of visible light. These materials appear exceptionally dark because almost no light bounces back to the viewer’s eyes. Ultrablack surfaces are important in areas such as optical instruments, cameras, telescopes, solar panels, and scientific sensors, where stray reflections can interfere with accuracy.

However, making ultrablack materials is difficult. Many existing versions rely on rigid carbon nanotube coatings or fragile surfaces that lose their deep black appearance when viewed from an angle. Others are not wearable, not scalable, or too expensive for everyday applications. The Cornell team set out to solve these problems.

Nature as the Blueprint

The research was inspired by the magnificent riflebird, a member of the bird-of-paradise family found in New Guinea and parts of Australia. This bird is famous for its intense black plumage, which appears almost unreal when viewed straight on.

The secret behind the bird’s appearance lies in two combined features: melanin pigment and a complex hierarchical feather structure. The feathers contain tightly packed microscopic barbules that bend and trap incoming light, forcing it inward instead of letting it reflect outward. While the bird can look shiny at certain angles, from a direct view it absorbs nearly all visible light.

The Cornell researchers studied real riflebird feathers obtained from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, with help from museum curators and collection managers. Their goal was not to copy the feathers exactly, but to recreate the same light-trapping principle in a textile.

The Two-Step Fabrication Process

The team developed a simple but clever two-step method to turn ordinary fabric into ultrablack material.

First, they started with white merino wool knit fabric and dyed it using polydopamine, a synthetic material that closely mimics melanin. Polydopamine was chosen deliberately because melanin is the pigment responsible for black coloration in many animals, including birds, fish, and insects. Unlike typical dyes that coat only the surface, polydopamine was allowed to penetrate deep into the fibers, ensuring that the entire fabric became uniformly black.

Second, the dyed fabric was placed inside a plasma etching chamber. Plasma etching removes tiny amounts of material from the fiber surface at a microscopic scale. This process created nanofibrils, which are spiky, nanoscale structures that grow outward from the fibers.

These nanofibrils are the key to the ultrablack effect. When light hits the fabric, it becomes trapped between these tiny spikes, bouncing back and forth instead of reflecting outward. Each bounce increases the chance that the light will be absorbed by the material rather than escaping.

Record-Breaking Optical Performance

Tests showed that the finished fabric has an average total reflectance of just 0.13%, meaning it absorbs 99.87% of incoming light. This makes it the darkest fabric reported so far in scientific literature.

Equally important, the fabric maintains its ultrablack appearance across a 120-degree viewing range, staying visually black even when viewed from up to 60 degrees off-center. Many commercial ultrablack materials lose their effect when viewed at an angle, but this textile does not.

Because the nanostructures are integrated into the fibers themselves rather than applied as a fragile coating, the fabric remains soft, flexible, and wearable.

Why Wearable Ultrablack Matters

Most existing ultrablack materials are not suitable for clothing or flexible surfaces. Carbon nanotube forests, for example, are extremely effective at absorbing light but are also delicate, rigid, and unsafe to touch. The Cornell fabric changes this landscape by proving that ultrablack can be both high-performance and wearable.

The researchers successfully applied their method not only to wool, but also to other natural fibers such as cotton and silk, suggesting that the process could be adapted for a wide range of textile applications.

Fashion Meets Science

To demonstrate the material’s real-world potential, a Cornell fashion design student created a strapless black dress inspired by the magnificent riflebird. The ultrablack fabric was used as the centerpiece, paired with deep-black textiles and a touch of iridescent blue.

The dress served as a visual test. When photos of the garment were digitally adjusted for contrast, brightness, hue, and saturation, all colors changed except the ultrablack sections, which remained visually unchanged. This confirmed just how effectively the fabric absorbs light.

Potential Applications Beyond Clothing

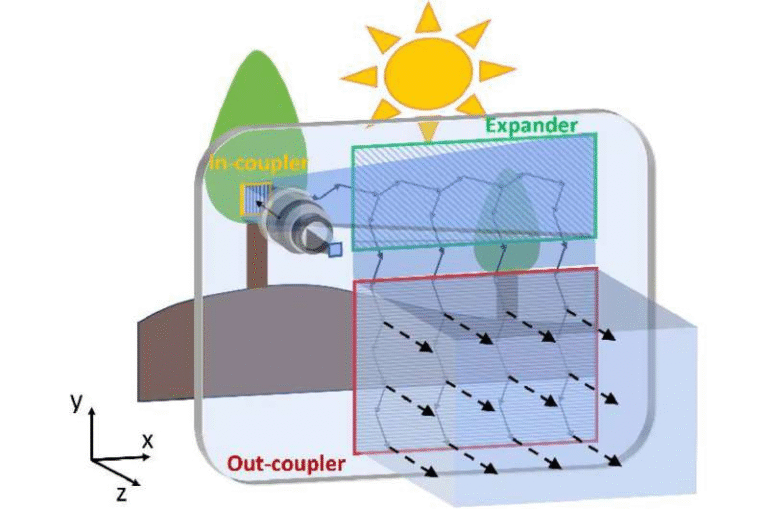

While fashion is one exciting area, the potential uses extend far beyond apparel. The fabric could play a role in solar thermal systems, where absorbing as much light as possible is essential for converting sunlight into heat. It may also be useful for thermo-regulating camouflage, helping control heat absorption in outdoor or military applications.

In science and engineering, the fabric could be used in optical instruments, imaging systems, sensors, and space technology, where reducing unwanted reflections improves performance. Because the process is relatively simple and scalable, it offers a practical alternative to existing ultrablack coatings.

Commercial and Research Outlook

The research team has filed for provisional patent protection through Cornell’s technology licensing office and is exploring pathways toward commercialization. They hope to launch a company and participate in innovation acceleration programs to bring the fabric closer to market.

The work also highlights a broader trend in materials science: using biological inspiration to solve engineering problems. From butterfly wings to shark skin to bird feathers, nature continues to provide efficient solutions refined over millions of years.

Understanding Ultrablack in a Broader Context

Ultrablack materials have captured public attention in recent years, especially with the development of materials like Vantablack, one of the darkest substances ever made. However, Vantablack and similar materials are typically restricted to industrial or artistic uses due to handling limitations.

What sets this new fabric apart is its combination of extreme light absorption, durability, flexibility, and manufacturability. It shows that ultrablack no longer needs to be confined to laboratories or museums—it can exist in everyday materials.

As research continues, fabrics like this could redefine how designers, engineers, and scientists think about color, light, and material performance.

Research paper: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65649-4