Dinosaurs in New Mexico Were Thriving Until the Very End, Study Finds

For decades, scientists believed dinosaurs were already in decline long before the asteroid struck Earth about 66 million years ago, wiping them out in one of the most famous extinction events in history. But new research has completely overturned that narrative. A team of researchers from Baylor University, New Mexico State University, the Smithsonian Institution, and other international collaborators have found solid evidence that dinosaurs in New Mexico were not just surviving but actually flourishing right up to the moment of impact.

The study, published in the journal Science, focuses on fossils from the Naashoibito Member of the Kirtland Formation in northwestern New Mexico’s San Juan Basin. Using modern high-precision dating methods, the researchers concluded that these fossils date to between 66.4 and 66.0 million years ago, meaning these dinosaurs were alive mere hundreds of thousands of years before the asteroid ended the Cretaceous Period.

A Hidden Chapter in the San Juan Basin

The San Juan Basin, located in northwestern New Mexico, is a treasure trove for paleontologists. Within its layered rocks lies the Naashoibito Member, a lesser-known geological formation that preserves fossils from the very end of the Cretaceous Period. For years, the timing of these fossils was uncertain, making it difficult to compare them with dinosaur fossils from other regions.

By applying high-precision geochronological techniques—methods that date rocks based on radioactive decay and magnetic signatures—the research team nailed down the timeline with remarkable accuracy. Their results show that the dinosaurs preserved here lived at almost the exact same time as those in the famous Hell Creek Formation found in Montana and the Dakotas.

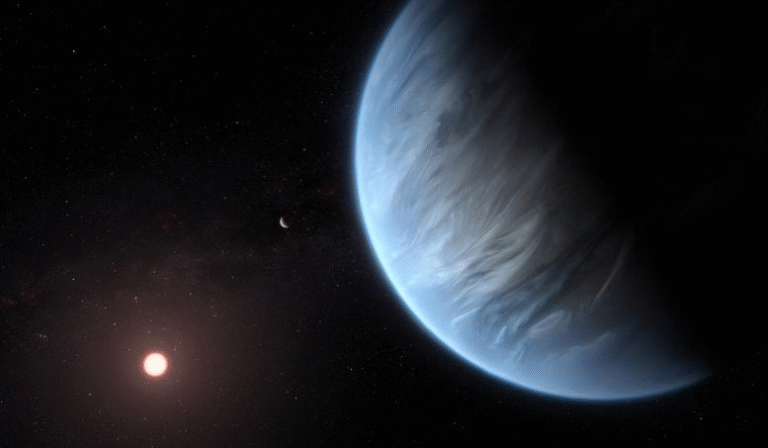

This means that dinosaurs in what is now New Mexico and those farther north were living side by side in time, but not necessarily in the same kind of environments. The findings provide a detailed snapshot of life just before the asteroid impact and show that dinosaurs in the southwest were thriving, diverse, and well-adapted to their local ecosystems.

Not a Decline — But a Final Flourish

One of the biggest takeaways from the study is that dinosaurs were not fading away before the impact. Contrary to older theories suggesting a long, slow decline in diversity, the fossils show a vibrant and regionally distinct ecosystem.

The researchers analyzed the fossilized remains of dinosaurs like Alamosaurus, a massive long-necked sauropod that once roamed what was then a warm and semi-arid landscape. They also found remains of other species that differ significantly from those found farther north, indicating that different “bioprovinces” existed across North America at the time.

These bioprovinces weren’t separated by mountains or rivers but rather by temperature differences. Northern regions like Montana and the Dakotas were cooler, while southern regions such as New Mexico were warmer. As a result, different species thrived in each area.

This regional variation shows that dinosaur ecosystems were complex and healthy—far from collapsing. It suggests that the asteroid impact was an abrupt and catastrophic event that wiped out thriving ecosystems, not a world already on the brink of collapse.

What the Discovery Tells Us About the End of the Dinosaurs

The timing of these fossils—so close to the Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) boundary—matters enormously. It narrows the gap between the last known dinosaur fossils and the impact itself, reinforcing the idea that dinosaurs were doing fine until the moment disaster struck.

This challenges decades of thinking that portrayed dinosaurs as slowly dying out. Instead, they were living in stable, productive ecosystems right up to the point when the asteroid impact unleashed fires, darkness, and a global winter that decimated food chains.

In other words, the asteroid didn’t just finish off a dying lineage—it abruptly ended an era of thriving biodiversity.

The Mammals Who Came After

Interestingly, the study also sheds light on what happened after the extinction. Within roughly 300,000 years of the asteroid impact, mammals began to diversify rapidly. These early mammals—small, adaptable, and opportunistic—took advantage of the empty ecological niches left behind by the dinosaurs.

What’s fascinating is that the same temperature-driven “bioprovinces” seen in the late dinosaur world persisted into the Paleocene Epoch. Mammals in the northern regions remained distinct from those in the south, echoing the same north-south ecological split that existed before the extinction. This continuity shows that climate patterns continued to shape ecosystems even as new species emerged to fill the void.

Why This Discovery Matters Today

Beyond rewriting the story of dinosaur extinction, this discovery highlights the importance of public lands and careful fossil protection. The fossils were found on land managed by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, showing how government-protected landscapes can provide invaluable scientific insights into Earth’s past.

The research also has broader implications for understanding how ecosystems respond to sudden global changes. Just as the dinosaurs’ world ended abruptly due to a cosmic impact, modern ecosystems face abrupt changes due to human activity and climate shifts. Studies like this remind us that biodiversity can be thriving one moment and gone the next if global systems collapse too quickly for species to adapt.

By understanding how ecosystems rebounded after the asteroid, scientists can gain insight into how life might respond to rapid environmental changes today.

A Closer Look at Alamosaurus

Since Alamosaurus plays a central role in this discovery, it’s worth taking a moment to understand this fascinating creature. Alamosaurus was one of the largest dinosaurs ever found in North America, reaching up to 30 meters (100 feet) in length and weighing over 70 tons. It belonged to a group known as titanosaurs, massive plant-eating sauropods that dominated southern regions during the Late Cretaceous.

Unlike many other sauropods that had already disappeared from North America, Alamosaurus persisted until the very end of the Cretaceous, which makes it a perfect example of dinosaurs thriving up to the boundary. Its presence in New Mexico’s fossil record is proof that the southern ecosystems were still rich and productive right before the extinction event.

How Scientists Date Dinosaur Fossils

One of the reasons this study is so significant is the precision of the dating techniques used. Traditional fossil dating often relies on indirect evidence, such as comparing fossil layers with others of known age. But the researchers here used high-resolution radiometric dating—specifically, methods that analyze volcanic minerals like sanidine—to pinpoint the ages of rock layers with unprecedented accuracy.

They also used magnetostratigraphy, a technique that studies changes in Earth’s magnetic field recorded in rock layers, to cross-check the results. These techniques confirmed that the Naashoibito fossils formed right before the global mass extinction.

This level of precision is crucial because it allows scientists to connect the dots between fossil evidence and global geological events like asteroid impacts or volcanic eruptions.

What Comes Next

This discovery has opened new questions. Were other regions across the world showing similar levels of late Cretaceous diversity? Were all dinosaur species thriving equally, or were some beginning to decline while others flourished? Future studies in South America, Asia, and Africa will be key to understanding whether this pattern was global or specific to North America.

For now, what’s clear is that dinosaurs in New Mexico were not limping toward extinction—they were living strong, diverse, and dynamic lives until the final, catastrophic moment.

The new findings remind us that extinction often comes suddenly, even to the mightiest creatures, and that Earth’s ecosystems—no matter how resilient—can change in an instant.

Research Reference:

Late-surviving New Mexican dinosaurs illuminate high end-Cretaceous diversity and provinciality – Science (2025)