Even One Drink May Raise Dementia Risk, Landmark Study Warns

A new study has just shaken up what many people believed about alcohol and brain health.

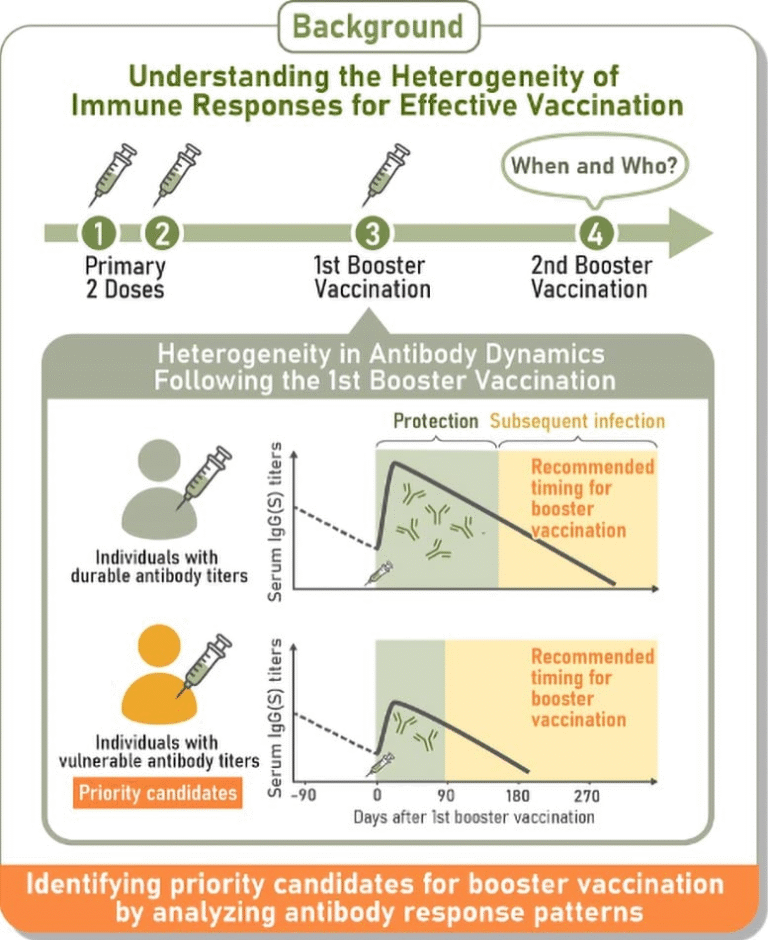

For years, some research suggested that light or moderate drinking might actually be protective, with a famous “J-shaped” or “U-shaped” curve often cited—where abstainers and heavy drinkers had higher risks, but moderate drinkers supposedly fared best. The latest evidence, however, strongly disputes this idea.

Published on 23 September 2025 in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine, the research concludes that there is no safe level of alcohol consumption when it comes to dementia. Instead, the risk of developing dementia increases steadily with each additional drink. Let’s break down the specifics of this landmark study, look at the methods, the numbers, and what it might mean for you.

Who Was Studied

The researchers pulled data from two massive biobanks:

- US Million Veteran Program (MVP) – includes participants of European, African, and Latin American ancestry.

- UK Biobank (UKB) – includes participants primarily of European ancestry.

In total, 559,559 people aged 56–72 at baseline were included in observational analyses. They were followed until they either:

- received a dementia diagnosis,

- died, or

- reached the end of the study’s follow-up period (December 2019 for MVP, January 2022 for UKB).

The average monitoring period was 4 years in the US group and 12 years in the UK group.

Alcohol Data and Screening

Alcohol use was measured in two main ways:

- Self-reported questionnaires – over 90% of participants reported being drinkers.

- AUDIT-C (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test) – a clinical tool that screens for hazardous drinking, including binge drinking (6 or more drinks at once).

This combination allowed researchers to capture both regular drinking levels and risky patterns of consumption.

Observational Findings

Out of the 559,559 participants:

- 14,540 developed dementia (10,564 in the US group; 3,976 in the UK group).

- 48,034 died during the follow-up (28,738 in the US group; 19,296 in the UK group).

The observational data showed a U-shaped relationship:

- Compared with light drinkers (fewer than 7 drinks a week):

- Non-drinkers had a 41% higher risk of dementia.

- Heavy drinkers (40+ drinks a week) also had a 41% higher risk.

- Those diagnosed as alcohol dependent had a 51% higher risk.

At first glance, this might look like moderate drinking is protective. But the researchers point out a major issue: reverse causation. Many people who later developed dementia had actually reduced their alcohol consumption in the years leading up to diagnosis, making it falsely appear as if light drinking offered protection.

Genetic Analyses: Mendelian Randomization

To get around the pitfalls of observational studies, the researchers used Mendelian randomization (MR), a method that leverages genetic variants associated with alcohol use. Because genes are randomly assigned at conception, this method is less affected by lifestyle confounding factors.

The MR analyses drew from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) involving 2.4 million participants. Researchers looked at three different genetic exposures:

- Weekly alcohol consumption (641 variants)

- Problematic “risky” drinking (80 variants)

- Alcohol dependence (66 variants)

Results showed:

- An extra 1–3 drinks per week was linked to a 15% higher risk of dementia.

- A doubling of genetic risk for alcohol dependence was tied to a 16% higher risk of dementia.

Most importantly, the genetic data revealed a linear increase in dementia risk with alcohol consumption. There was no protective effect at low levels—risk simply went up with more drinking.

Why Earlier Studies Got It Wrong

Previous observational research often failed to properly separate lifelong abstainers from former drinkers who quit because of health issues. This oversight introduced bias, making it look like not drinking carried higher risks.

The new study also found that people who went on to develop dementia typically reduced their drinking over time before diagnosis. This helps explain why moderate drinking sometimes appeared beneficial in earlier research.

Limitations of the Study

Like all scientific work, this study has its caveats:

- The strongest statistical associations were seen among people of European ancestry, since they made up most of the sample.

- Mendelian randomization relies on certain assumptions that cannot be fully verified.

- Self-reported alcohol data may be prone to underreporting.

Despite these limitations, the researchers argue that the evidence strongly challenges the idea of any safe or protective level of alcohol for dementia risk.

What This Means for You

The findings suggest that reducing alcohol intake at any level may help lower dementia risk. Even cutting down from a few drinks per week could make a measurable difference.

This is especially relevant for public health: if alcohol dependence truly raises dementia risk by about 16%, then reducing problematic drinking at the population level could prevent a significant number of dementia cases.

Understanding Dementia and Its Burden

To appreciate the impact of this study, it helps to remember what dementia is.

- Dementia is not a single disease but a syndrome involving memory loss, cognitive decline, and changes in behavior.

- Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form, but vascular dementia and other types also exist.

- Dementia currently affects over 55 million people worldwide, with nearly 10 million new cases every year, according to the World Health Organization.

Given that dementia has no cure, prevention strategies—like reducing alcohol use—become incredibly important.

Alcohol and the Brain: What We Already Know

Science has long linked alcohol to negative brain effects:

- Heavy drinking can cause alcohol-related brain damage, including Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome.

- Binge drinking increases the risk of traumatic brain injury and stroke, both of which contribute to dementia.

- Even moderate drinking is associated with brain volume loss, particularly in the hippocampus (a key memory center).

The new study adds another layer, suggesting that even low levels of alcohol consumption are not free from risk.

Alcohol in Cultural Context

Alcohol has a long history in human societies. From wine in ancient Greece to beer in Mesopotamia, it has played social, religious, and economic roles.

But in modern times, global health guidelines are tightening. For example:

- Canada’s 2023 guidelines recommend no more than 2 drinks per week.

- The World Health Organization has stated there is no safe level of alcohol when it comes to cancer risk.

This new dementia research lines up with these stricter positions.

Looking Ahead

The study’s authors emphasize the importance of addressing reverse causation and residual confounding in alcohol research. Their conclusion is clear:

- All types of alcohol increase dementia risk.

- No evidence supports a protective effect of moderate drinking.

Future studies may look at interventions—such as whether reducing alcohol intake in midlife actually lowers dementia rates later on. But for now, the safest advice appears simple: less is better.

Final Thoughts

For many, the idea that “a glass of wine a day is good for you” has been comforting. This new evidence says otherwise. The data is robust, combining observational and genetic approaches, and it consistently shows that alcohol—even in small amounts—adds to dementia risk.

The takeaway is not about panic, but about clarity. If protecting your brain health is a priority, lowering alcohol consumption could be one of the most effective steps you can take.