High-Precision Plasma Potential Measurements Bring Fusion Research a Big Step Closer to Reactor-Ready Conditions

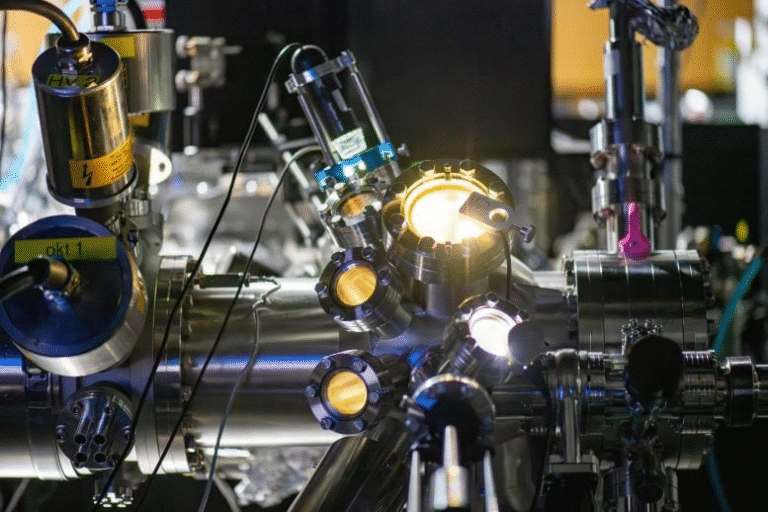

Scientists working with Japan’s Large Helical Device (LHD) have achieved the first high-precision measurement of electric-potential dynamics inside reactor-grade fusion plasma, and the results could meaningfully improve how future fusion reactors are designed and controlled. This work centers on a major upgrade to a diagnostic tool called the Heavy Ion Beam Probe (HIBP), which researchers rely on to directly measure the internal electric potential of super-hot fusion plasma — a property that plays a crucial role in energy confinement, plasma stability, and overall reactor performance.

Below, I’ll walk through exactly what the researchers did, why it matters, the technical challenges they solved, and how this may shape the future of fusion energy. I’ll also add helpful background sections so readers understand how HIBP works, why electric potential matters, and how devices like LHD operate.

Understanding the Goal: Measuring Electric Potential in Fusion Plasma

Fusion plasma must be confined at temperatures above one hundred million degrees, and magnetic fields do most of the heavy lifting. But inside that turbulent, high-energy environment, another crucial player is the plasma’s electric potential — essentially, the internal electrical landscape that influences how particles move and how energy is transported.

A stable and well-shaped electric-potential profile supports better confinement. If researchers can precisely measure how this potential forms, changes, and collapses, they can better understand the conditions that lead to good performance or sudden losses of confinement. That’s where the Heavy Ion Beam Probe comes in.

But until now, HIBP systems could not deliver high-precision measurements in reactor-grade plasma because their ion beams weren’t strong or stable enough. This new work changes that.

What the Heavy Ion Beam Probe Actually Does

The HIBP system injects a stream of negatively charged gold ions (Au⁻) into the plasma. These ions are:

- Generated at a negative ion source

- Accelerated in a multistage accelerator

- Converted into Au⁺ (positive ions) inside a tandem accelerator

- Further accelerated to 6 mega–electron volts (MeV)

- Sent through the plasma, where collisions turn some ions into Au²⁺

- Measured on the other side

By comparing the energy of the injected beam (Au⁺) with the energy of the beam after it’s been inside the plasma (Au²⁺), researchers can calculate the local electric potential where the charge-state change happened.

This technique gives a direct, non-contact measurement of plasma potential, but only if the injected beam is strong, focused, and stable — something that has historically been very difficult with heavy ions like gold.

The Technical Problem: Beam Losses From Space-Charge Expansion

Even though the negative-ion source could produce more beam current in recent years, the beam entering the tandem accelerator didn’t increase proportionally. Something was blocking progress.

Using the IGUN ion-beam transport simulation code, researchers found that:

- At low currents (below 10 microamperes (µA)), the Au⁻ beam passed through the entrance slit smoothly.

- At higher currents, space-charge effects caused the beam to expand.

- This expansion made the beam miss the narrow entrance, leading to large beam losses before acceleration.

Space-charge effect means that the like-charged ions in the beam repel each other more strongly at higher densities, similar to how a tightly packed group of magnets pushes itself apart. Heavy ions like gold are especially sensitive to this issue.

This created a bottleneck: even with stronger ion sources, most of the beam simply didn’t survive the transport stage.

The Breakthrough: Turning the Multistage Accelerator Into an Electrostatic Lens

Rather than redesigning the equipment physically, the team optimized the voltage distribution of the multistage accelerator between the ion source and the tandem accelerator.

Normally, this section’s primary role is basic acceleration, but the researchers realized that with carefully tuned voltages, it could also function as an electrostatic lens. This lens counteracts space-charge spreading by focusing the beam.

Simulations showed:

- A high-transmission region exceeding 95% became possible.

- Transport efficiency dramatically improved beyond conventional setups.

Real-world plasma experiments confirmed the prediction. The Au⁻ beam reaching the accelerator increased by a factor of two to three, and because the entire injection chain became more efficient, the Au⁺ beam entering the plasma also grew stronger.

This upgrade improved both the signal clarity and the measurement range of the HIBP system.

What the Researchers Measured in the Plasma

Thanks to the stronger beam, researchers could measure the internal plasma potential even at higher electron densities up to 1.75 × 10¹⁹ m⁻³, which is closer to reactor-grade operating conditions.

They tracked the potential profile during specific transitions in heating methods:

- At 4.0 seconds: the plasma was heated by electron cyclotron heating (ECH).

- At 6.1 seconds: 0.1 seconds after ECH was turned off.

- At 7.0 seconds: heating was provided by a 180 keV neutral beam injection (NBI).

During these transitions, the researchers observed:

- A rapid decrease in overall plasma potential immediately after ECH termination.

- A gradual flattening of the potential profile afterward.

These dynamics matter because electric-potential changes can alter particle transport, turbulence behavior, and overall plasma confinement. With higher precision data, scientists can refine predictive plasma-physics models and develop more effective confinement strategies.

Why This Matters for Future Fusion Reactors

Fusion reactors will require real-time understanding and control of the plasma’s internal structure. High-precision potential measurements like these:

- Improve the accuracy of plasma-transport and turbulence models

- Help fusion scientists identify what leads to improved or degraded confinement

- Allow for better reactor design, especially in shaping magnetic and electric fields

- Support the development of advanced feedback-control systems

- Provide the fundamental data needed to move from experimental devices to self-sustaining reactors

Importantly, the method developed here is practical and compact—no large mechanical alterations, just optimized voltage tuning. This makes it possible for many other fusion devices and accelerator-based diagnostics to benefit from the same approach.

Background: Why Electric Potential Inside Plasma Is So Important

Inside magnetic-confinement fusion devices, the electric potential influences:

- Radial electric fields, which can suppress or enhance turbulence

- Particle drift, affecting where heat and fuel travel

- Transport barriers, which improve confinement

- Stability of plasma configurations

Experiments across devices like tokamaks and stellarators consistently show that changes in electric potential correlate strongly with performance improvements or degradations.

Achieving high-precision measurements of these internal fields has been a longstanding challenge, especially in high-density, reactor-like plasmas. This new work helps fill that gap.

Background: What Makes the Large Helical Device Special

The Large Helical Device (LHD) is one of the world’s largest superconducting stellarators. Its twisted magnetic coils maintain plasma confinement without needing the large plasma current that tokamaks rely on. This makes LHD an excellent platform for studying stable, long-duration plasmas.

LHD is particularly suited for advanced diagnostics because:

- It supports long discharges

- It provides steady-state confinement

- It allows controlled transitions between heating schemes

- It operates at densities and conditions relevant to future reactors

The new HIBP improvements strengthen LHD’s position as a major contributor to fusion-diagnostics research.

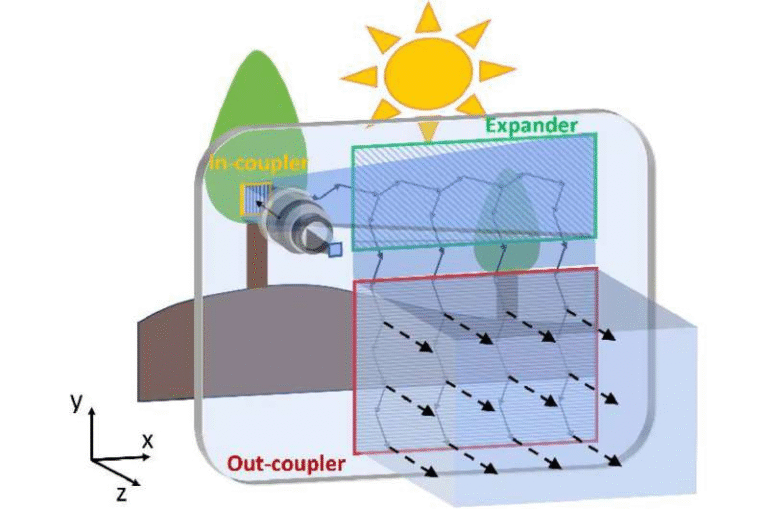

Background: The Heavy Ion Beam Probe in Simple Terms

If you think of fusion plasma as a storm of charged particles, measuring its internal electric potential is like trying to determine the heights of ocean waves from outside the water. HIBP provides a way to “touch” the inside of the plasma without physically entering it.

By injecting high-energy heavy ions, the system uses their energy changes like a probe. But that only works if the injected beam is intense and stable — exactly what this research has improved.

Research Paper Reference

Enhanced beam transport via space charge mitigation in a multistage accelerator for fusion plasma diagnostics

https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-4326/ae0da1