MIT Researchers Develop a Framework to Identify the Smallest Dataset Needed for Optimal Decision-Making

A team of researchers at MIT has introduced a new algorithmic method that pinpoints the smallest possible dataset required to guarantee an optimal solution in complex decision-making problems. This approach is designed for situations where gathering data is expensive, time-consuming, or resource-intensive—such as planning subway routes beneath major cities, optimizing supply chains, or managing energy networks. Instead of following the usual mindset of collecting more data to improve accuracy, this framework shows that under structured conditions, very small but carefully selected datasets can provide guarantees of optimality.

The research comes from MIT’s Departments of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science as well as Civil and Environmental Engineering, involving Asu Ozdaglar, Saurabh Amin, and co-lead authors Omar and Amine Bennouna. Their paper is set to be presented at NeurIPS 2025, one of the most prominent conferences in artificial intelligence and machine learning.

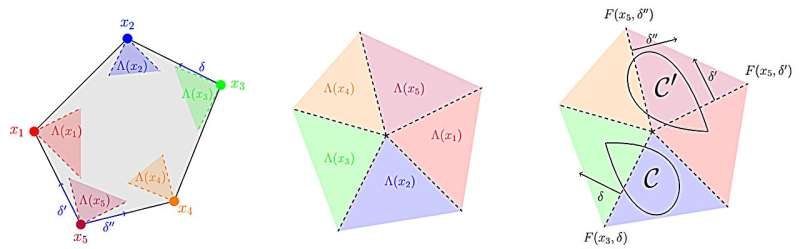

XX and to the origin, respectively. The right panel presents example uncertainty sets (C

CC and C′C’C′) in relation to these cones. Credit: arXiv (2025).

Understanding the Core Problem

Many real-world decisions rely on datasets involving uncertain parameters—like construction costs, travel times, or energy prices. Traditionally, models assume these data points already exist, or they demand large datasets to reduce uncertainty. The MIT team, however, flipped the idea around and asked a more fundamental question:

What is the minimum amount of information needed to guarantee the correct decision?

To study this, they looked at a class of problems called linear optimization problems, which include many common operations-research and engineering tasks. In these problems, the outcome depends on a cost vector—values like travel time or construction expense—that may be partially unknown. Since collecting all these cost values can be expensive, the challenge is deciding which ones actually matter.

Their method provides a mathematical way to identify exactly which data points must be collected in order to guarantee an optimal decision, and nothing more.

How the New Framework Works

The researchers built a geometric and mathematical characterization of something they call optimality regions. Every possible set of cost values leads to a specific decision being optimal. These regions effectively partition the decision space.

A dataset is considered sufficient if it provides enough information to determine which region the true cost values belong to. In other words, even if you don’t know every cost precisely, you know enough to identify which option is the best one.

Key aspects of their framework include:

- A precise mathematical theory of dataset sufficiency

- An iterative algorithm that checks whether the current dataset can distinguish between all possible optimal decisions

- A method for adding only the most critical measurements when additional information is needed

- A companion algorithm that, once the sufficient dataset is collected, computes the exact optimal solution

This means the framework not only tells you where to collect data but also how to use it.

Example: Planning a Subway Line

The researchers describe a scenario in which a city wants to build a subway line beneath a complicated grid like New York City. Surveying underground construction costs across hundreds of city blocks is extremely expensive.

Using the new algorithm:

- The planner enters the structure of the problem (available routes, constraints, budget).

- They specify the uncertainties (which costs are unknown or variable).

- The algorithm identifies the minimum set of blocks that must be surveyed.

Despite the enormous number of possible routes, the method might determine that only a small subset of cost measurements is enough to guarantee the truly least-cost path.

This avoids unnecessary surveys and saves time, money, and labor.

Applications Beyond Infrastructure

The framework applies to a wide range of domains where decisions depend on uncertain parameters:

Supply Chain Optimization

A company aiming to minimize shipping costs across dozens of routes may have partial knowledge about some routes but large uncertainty about others. The new method tells them exactly which routes they must evaluate to guarantee optimal decisions.

Electricity and Resource Networks

Energy grids involve fluctuating costs, capacities, and constraints. Instead of gathering massive datasets, energy operators could use the algorithm to identify the critical measurements that determine the best operational strategy.

Operations Research and AI Training

Because the framework emphasizes data efficiency, it challenges the common “big data” assumption. In many tasks, training on a smaller, well-chosen dataset can produce exactly optimal outcomes without wasting computational resources.

Why Small, Targeted Data Can Be Better

One of the major misconceptions in decision science is that small datasets inevitably lead to approximate or suboptimal solutions. The MIT team shows this isn’t always true. Under structured problem settings:

- You don’t need to estimate every uncertain value.

- You only need enough data to tell two competing solutions apart.

- With the right theoretical characterization, you can guarantee exact optimality.

This shifts the emphasis from quantity to relevance.

How the Algorithm Selects Data

The algorithm repeatedly asks a simple but powerful question:

“Is there any possible scenario where the true optimal decision changes but the current dataset can’t detect it?”

If yes, then it identifies a measurement that would resolve that ambiguity.

If no, the dataset is sufficient.

This ensures the resulting dataset meets a strong guarantee:

For every uncertainty that falls within the defined bounds, the optimal decision will be correctly identified.

Such guarantees are rarely provided in data-efficient methods, which often rely on probabilistic or heuristic approximations.

Expert Reception

Yao Xie, a well-known professor at Georgia Tech, described the work as original, clear, and offering an elegant geometric understanding of data sufficiency in decision-making. Experts view the framework as a meaningful advancement in the theory of optimization under uncertainty, especially because it provides exact conditions rather than heuristic guidance.

Future Directions

The authors aim to extend the framework to:

- More complex optimization problems (nonlinear, combinatorial)

- Scenarios involving noisy or imperfect data

- Broader uncertainty models

They also want to explore how real-world noises—errors in surveys, sensor imprecision, or human mistakes—might affect sufficiency guarantees.

Additional Background: Linear Optimization and Why It Matters

Since the paper focuses on linear optimization, it’s helpful to understand why this class of problems is so important.

What Is Linear Optimization?

Linear optimization (or linear programming) involves maximizing or minimizing a linear objective subject to linear constraints. For example:

- Minimize cost

- Maximize profit

- Minimize energy usage

subject to limitations like capacities, budgets, and resource availability.

Why It’s Used Everywhere

Because it’s simple mathematically but powerful in practice, linear optimization underpins:

- Transportation planning

- Supply chain routing

- Energy distribution

- Manufacturing

- Telecommunications

- Finance and investment strategies

By improving how we gather data for these models, the MIT framework could significantly reduce the cost of solving real-world problems.

Additional Context: The Rise of Data-Efficient AI

In the broader AI landscape, there is a growing recognition that not all tasks benefit from huge datasets. Techniques like active learning, sublinear optimization, and sparse modeling also aim to reduce data needs. The MIT framework fits into this emerging trend but stands out because it provides provable guarantees rather than probabilistic confidence.

Reference

Research Paper:

What Data Enables Optimal Decisions? An Exact Characterization for Linear Optimization

https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.21692