New Research Takes a Fresh Look at Spinless Glueballs and the Hidden Structure of Subatomic Particles

Physicists have long believed that some of the most unusual forms of matter predicted by theory are still hiding in plain sight. A new study from SUNY Polytechnic Institute now adds important clarity to one of the most fascinating of these predictions: spinless glueballs, particles made entirely from the carriers of the strong force itself.

The research, led by Dr. Amir H. Fariborz, Professor of Physics at SUNY Poly, was recently published in Physical Review D under the title Spinless glueballs in generalized linear sigma model. The paper tackles a central challenge in modern particle physics — understanding how the strong interaction, the most powerful force in nature, shapes matter at its deepest level and whether it can produce particles built solely from gluons.

Understanding the Basics: Quarks, Gluons, and the Strong Force

At the most fundamental level, everything around us is made of atoms. Inside each atom is a nucleus composed of protons and neutrons, which themselves are built from smaller constituents known as quarks. These quarks are held together by gluons, particles that carry the strong force described by quantum chromodynamics (QCD).

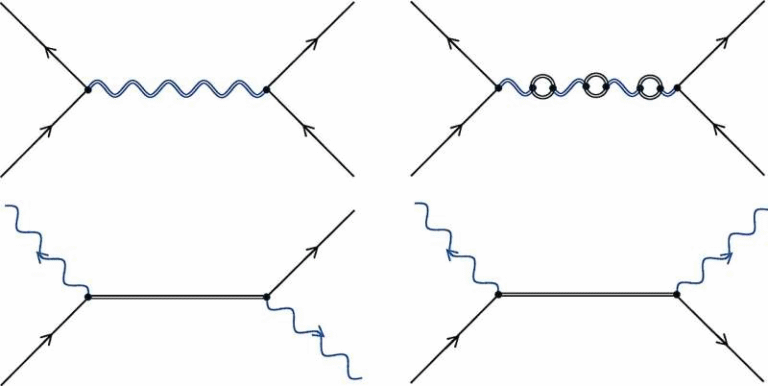

Particles made of quarks and gluons are known as hadrons, and they fall into two broad categories: mesons and baryons. Baryons, like protons and neutrons, contain three quarks, while mesons are typically made from a quark and an antiquark.

QCD works extremely well when particles collide at very high energies. However, at lower energies — the realm where most hadrons exist — the mathematics becomes incredibly difficult to solve exactly. To deal with this, physicists rely on carefully constructed models that respect the rules and symmetries of QCD while remaining practical to use.

What Are Glueballs and Why Are They So Hard to Find?

One of the most intriguing predictions of QCD is the existence of glueballs — particles composed entirely of gluons, with no quarks involved. If confirmed beyond doubt, glueballs would represent a completely new type of matter, made purely from force-carrying particles.

Despite decades of theoretical work and experimental searches, glueballs have not been cleanly and directly identified. The main reason is that glueballs can mix with ordinary mesons that have similar properties, such as the same spin and parity. When this mixing happens, the resulting particle no longer looks purely gluonic, making it extremely difficult to tell where the glueball ends and the meson begins.

There is, however, strong indirect evidence for glueballs. Large-scale lattice QCD simulations, which use powerful supercomputers to solve QCD numerically, consistently predict their existence and approximate mass ranges. Experiments have also observed candidate particles that do not fit neatly into traditional quark-based classifications.

The Generalized Linear Sigma Model Approach

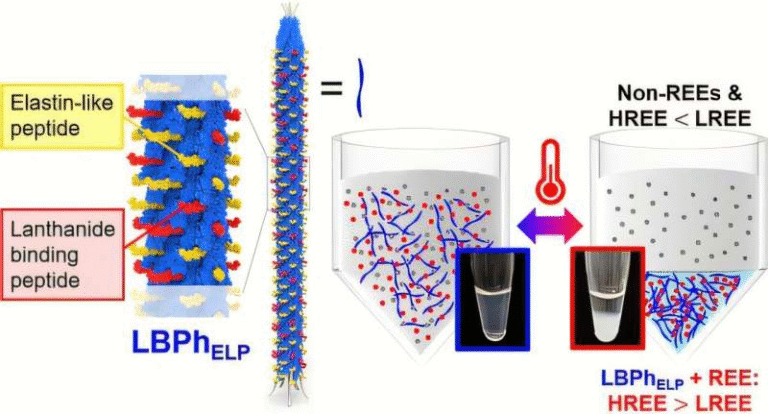

Dr. Fariborz’s new work uses the generalized linear sigma model, a framework he and his collaborators introduced more than two decades ago. This model has been widely applied to low-energy QCD processes and has repeatedly produced results consistent with experimental data.

What makes this model powerful is that it is built around the symmetries of the strong interaction, including key quantum anomalies that play a major role in determining particle masses and interactions. Rather than focusing on individual particles in isolation, the model looks at how entire families of particles behave and mix with one another.

In this study, the model includes two types of meson structures:

- A quark–antiquark nonet

- A four-quark nonet

Both scalar and pseudoscalar particles are considered, along with corresponding scalar and pseudoscalar glueball fields.

Scalar vs Pseudoscalar Particles Explained

In particle physics, scalar particles have zero spin and positive parity, while pseudoscalar particles also have zero spin but negative parity. These properties strongly influence how particles interact and decay.

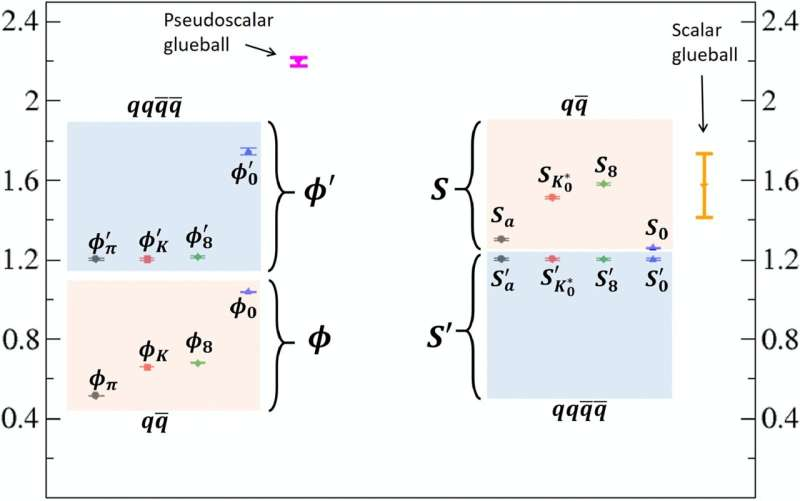

The study carefully analyzes both sectors and reveals an interesting contrast:

- In the pseudoscalar sector, the quark–antiquark nonet is lighter than the four-quark nonet.

- In the scalar sector, the situation is reversed, with the four-quark nonet being lighter than the quark–antiquark one.

This inversion is an important clue for understanding how different internal structures contribute to observed particle masses.

Why Two Pseudoscalar Glueballs Are Needed

One of the most striking conclusions of the paper is that properly reproducing known experimental data requires two pseudoscalar glueball fields, not just one.

One of these glueballs corresponds to a physical state, while the other is an unphysical auxiliary field. When the unphysical field is mathematically removed from the theory, it generates an effective term similar to those associated with instantons, which are non-perturbative effects in QCD.

This mechanism turns out to be essential for correctly explaining the masses of the eta mesons, which are particularly sensitive to QCD’s axial anomaly. Without this structure, the observed eta mass spectrum cannot be reproduced accurately.

Mapping the Internal Structure of Dozens of Particles

In total, the study provides detailed predictions for 12 categories of particles, covering 36 distinct physical states. For each state, the model estimates how much of its internal structure comes from quark–antiquark components, four-quark components, and gluonic contributions.

The results suggest that:

- The most glue-rich pseudoscalar states lie above roughly 2 GeV.

- In the scalar sector, several particles in the 1.5–2.0 GeV range may contain significant glueball content.

These conclusions depend on the value of the scalar glueball condensate, a theoretical parameter related to how gluons interact with themselves in the vacuum.

Why This Matters for Experiments

From an experimental perspective, this work is especially valuable because it helps physicists interpret what detectors are actually seeing. Many observed particles in the scalar and pseudoscalar sectors have long puzzled researchers because they do not behave like simple quark–antiquark states.

By providing a consistent framework that includes glueballs and mixing effects, the generalized linear sigma model offers a roadmap for identifying which observed resonances are most likely to contain substantial gluonic components.

This does not mean glueballs will suddenly become easy to spot. Instead, it sharpens the theoretical picture and narrows down the list of realistic candidates, making future experimental searches more focused and informed.

The Bigger Picture in Strong Interaction Physics

Beyond glueballs themselves, this research represents a significant step forward in understanding low-energy QCD, a regime where many of the strong force’s most interesting phenomena occur. It highlights how effective theories, when carefully constructed and tested against data, can reveal deep insights even when exact calculations are impossible.

As experimental facilities continue to collect higher-quality data and lattice QCD simulations grow more precise, studies like this one will play a crucial role in connecting theory and observation.

Glueballs may still be hiding, but the net around them is getting tighter.

Research Paper Reference:

https://journals.aps.org/prd/abstract/10.1103/kllv-gj2b