New Species of Ancient Coelacanth Fossils Identified in the UK After 150 Years

A fascinating new study has revealed that dozens of fossil specimens sitting in British museum collections for over 150 years were not what scientists originally thought. These fossils, once believed to be the remains of a small marine reptile called Pachystropheus, have now been correctly identified as belonging to the so-called “living fossil” fish, the coelacanth. This discovery massively expands the known fossil record of coelacanths in the UK, particularly from the very end of the Triassic Period, about 200 million years ago.

Rediscovery in Plain Sight

The research, led by Jacob G. Quinn at the University of Bristol along with collaborators from the University of Uruguay, examined fossil collections from across the UK. While completing his Master’s in Palaeobiology, Quinn noticed striking similarities between fossils labeled as Pachystropheus and known coelacanth features. Upon closer inspection, and with the help of X-ray scans, it became clear that the bones were indeed fish remains.

What makes this discovery remarkable is how long these fossils have been overlooked. Many of them had been sitting in storage facilities and even on display in museums since the late 1800s, yet they were incorrectly identified as bones from lizards, mammals, or other reptiles. From just four previously recognized coelacanth fossils in the British Triassic record, scientists now recognize over fifty specimens.

Fossils From the Triassic Seas

The fossils date back to the Rhaetian stage of the Late Triassic, around 209 to 201 million years ago. At that time, the region that is now the UK was much warmer and situated closer to the equator. The landscape of the Bristol area and Mendip Hills was an archipelago of small islands surrounded by shallow tropical seas. These seas were home to a wide variety of life, including marine reptiles like Pachystropheus and now, as this study shows, a whole community of coelacanth fishes.

The specimens include bones from individuals of different ages, sizes, and even species, suggesting that these fish were not rare visitors but part of a thriving ecosystem. Some of the coelacanths would have reached up to one meter in length, while larger bones such as clavicles suggest individuals up to 1.4 to 1.5 meters long.

Most of the fossils belong to the extinct family Mawsoniidae, which were close relatives of the coelacanths still alive today. This finding also reveals that Mawsoniid coelacanths were more widespread across Europe in the Triassic than previously thought.

How They Were Misidentified

The misidentification stems from the uncanny resemblance between certain coelacanth bones and those of Pachystropheus, a small marine reptile that lived at the same time. For decades, paleontologists assumed these fossils belonged to Pachystropheus because of shared skeletal features. By using modern imaging techniques such as CT scans and X-rays, the researchers could compare the fossils in detail and clearly distinguish the fish bones from reptile bones.

Key diagnostic features included the structure of the basisphenoid (a bone at the base of the skull), the ornamentation on the opercular plates (part of the gill cover), and the shape of the shoulder girdle bones like the clavicles. These matched with known coelacanth anatomy, and in particular, with large members of the Mawsoniidae family.

Insights Into Ancient Ecosystems

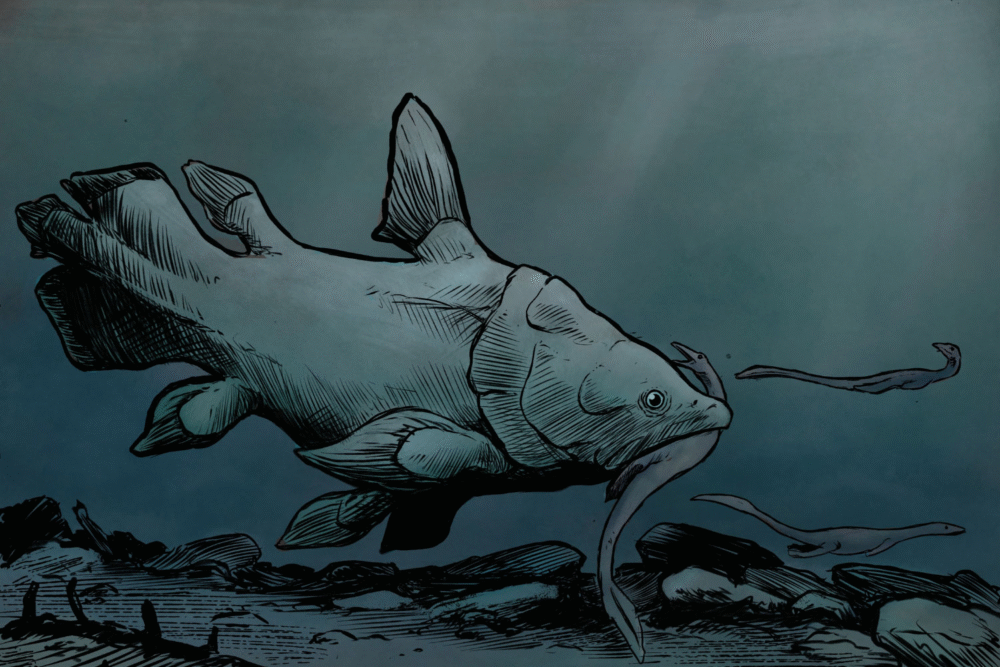

The reinterpretation of these fossils paints a new picture of the Late Triassic seas in what is now Britain. Rather than being dominated by reptiles alone, these waters supported large, slow-moving, opportunistic predators like coelacanths. Much like their modern relatives, Triassic coelacanths likely lurked near the seafloor, eating whatever prey they encountered.

It is even possible that these fishes preyed on Pachystropheus, the very reptile species with which their fossils were confused for so long. The fossils’ variation in size and morphology suggests a complex coelacanth community, with multiple age groups and possibly different species coexisting in the same shallow waters.

This discovery also reinforces the idea that coelacanths were not just rare, isolated species. Instead, they may have been significant predators in Late Triassic marine ecosystems, playing an important role in the food web.

Why This Discovery Matters

Correctly identifying these fossils has several implications:

- Expands the fossil record: The number of known British Triassic coelacanth fossils has increased from four to more than fifty, providing a much richer picture of their diversity.

- Reveals hidden diversity: Old museum collections can still hold valuable surprises. Misidentified specimens may be waiting to be correctly classified using modern techniques.

- Clarifies habitat preferences: Mawsoniid coelacanths were not confined to deep waters. They thrived in shallow, nearshore, and possibly brackish environments.

- Shifts ecological understanding: These fishes were not relics on the margins but may have been prominent in nearshore ecosystems, influencing the dynamics of predator-prey relationships.

What Exactly Are Coelacanths?

The coelacanth is often called a “living fossil” because it represents a lineage that has changed relatively little over hundreds of millions of years. For a long time, scientists believed coelacanths had gone extinct at the end of the Cretaceous, along with the dinosaurs. That assumption was shattered in 1938, when a living coelacanth was caught off the coast of South Africa.

Today, two species of coelacanth are known:

- Latimeria chalumnae, found near the Comoros Islands in the Indian Ocean.

- Latimeria menadoensis, discovered in Indonesia in 1997.

These modern coelacanths can grow up to two meters long and live in deep waters, usually between 150 and 700 meters. They are nocturnal hunters, feeding on fish and squid.

One of the most distinctive features of coelacanths is their lobed fins, which are fleshy and extend from the body on stalks of bone and muscle. These fins are considered important in the study of vertebrate evolution because they are structurally similar to the limbs of the first land-dwelling tetrapods.

Mawsoniidae: The Extinct Giants

The fossils discovered in the UK mostly belong to the extinct family Mawsoniidae, which lived from the Triassic to the Cretaceous. Unlike modern coelacanths, many Mawsoniids lived in shallow or brackish waters rather than the deep ocean.

Some species in this group, such as Mawsonia gigas from Brazil, could grow up to six meters long, making them true giants among coelacanths. The newly re-identified British fossils show that while the UK specimens were smaller, reaching up to 1.5 meters, they still represented large predators within their ecosystem.

Lessons From the Study

This research highlights a few important lessons for paleontology:

- Museum collections are treasure troves: Many significant discoveries still await recognition in existing collections. Old fossils may be misclassified or overlooked until fresh eyes and new methods revisit them.

- Technology transforms identification: Tools like CT scanning and X-ray imaging allow paleontologists to study internal structures non-destructively, making it easier to correct past mistakes.

- Understanding ecosystems requires revision: Each new discovery adds depth to our knowledge of ancient ecosystems. Re-identifying these fossils changes how we view Late Triassic marine life in Britain.

The Bigger Picture

This discovery emphasizes how science is constantly self-correcting. For over a century, these fossils were assumed to be reptile remains. With modern tools and a detailed re-examination, they now reveal the presence of a thriving coelacanth community that had been hidden in plain sight.

The work of Quinn and his colleagues shows that even in well-studied places like British museums, there are still opportunities for breakthroughs. As paleontology progresses, more such “rediscoveries” may reshape our understanding of life’s history on Earth.

Reference

“Coelacanthiform fishes of the British Rhaetian” – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 2025