New WSU Test Flags Drugs That Could Be Dangerous for Cats

A new breakthrough from Washington State University (WSU) is giving veterinarians and pharmaceutical companies a powerful tool to keep cats safer. Researchers at WSU have developed a laboratory test that can identify which drugs might cause harmful or even life-threatening reactions in certain cats. This development could reshape how veterinary medicines are tested and labeled, especially for cats carrying a particular genetic mutation that affects how their bodies process drugs.

The test, designed by Dr. Katrina Mealey, a veterinary pharmacologist, and Neal Burke, a laboratory supervisor at WSU, helps detect whether a drug relies on a protective protein called P-glycoprotein to be safely metabolized. When that protein doesn’t function properly—due to a mutation or drug interactions—cats can suffer severe neurological side effects.

Understanding the Mutation Behind the Problem

At the center of this discovery is the MDR1 (ABCB1) gene, which encodes the P-glycoprotein (P-gp) transporter. This protein acts like a microscopic gatekeeper, pumping potentially harmful substances out of critical areas such as the brain, intestines, and liver. When it works properly, it prevents toxic levels of drugs from building up.

However, in some cats, a mutation in this gene—known as ABCB1 1930_1931del TC—stops the P-glycoprotein from doing its job. The mutation was first discovered by Dr. Mealey in 2015, and her new study takes that work further by identifying exactly which medications could cause trouble in cats with this defect.

According to WSU, about 6% of Maine Coon cats and roughly 1% of non-pedigreed cats in the U.S. and Europe may carry this mutation. That might sound like a small percentage, but given the millions of pet cats worldwide, that’s still a significant number at risk.

How the New Test Works

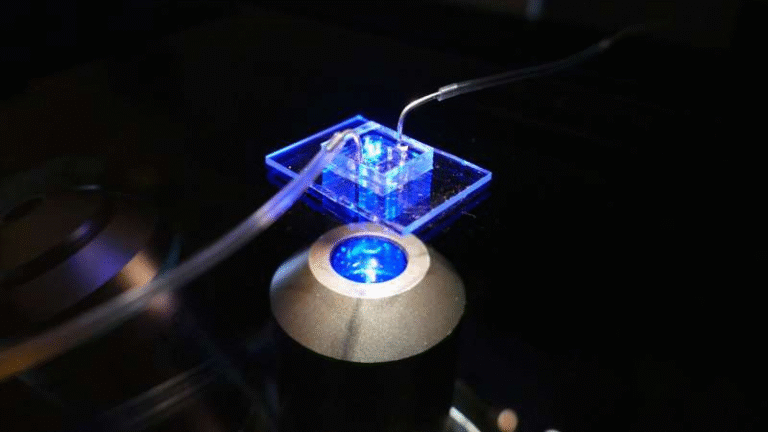

The WSU team’s test is straightforward but remarkably effective. It uses a feline cell culture—essentially a controlled environment with living cat cells—to mimic how drugs interact inside a cat’s body. Researchers add a fluorescent compound that normally gets cleared out of the cells by P-glycoprotein. Then they introduce the test drug.

If the test drug relies on P-glycoprotein to be processed, it competes with the fluorescent compound. When that happens, the compound can’t leave the cell, and it starts to glow brightly. This glowing effect signals that the drug is a P-gp substrate, meaning it depends on that transporter to be safely eliminated from the cat’s body.

Using this technique, the researchers screened 13 commonly used drugs in feline medicine. The results were striking:

- 10 of the 13 drugs were confirmed to be P-gp substrates, meaning they could cause toxicity in cats with the mutation.

- 3 drugs were found not to rely on P-glycoprotein and are likely safer for affected cats.

Drugs That Were Flagged as Risky

Among the drugs tested, several well-known medications showed strong dependence on P-glycoprotein. These include:

- Ivermectin, used to treat parasites, which showed extremely high P-gp dependence.

- Eprinomectin, another antiparasitic, also tested strongly positive.

- Vincristine and vinblastine, both chemotherapy agents, were flagged as significant substrates.

- Cyclosporine A, an immunosuppressant used for conditions like feline dermatitis, was identified as a P-gp substrate.

- Emodepside, found in some deworming medications, also made the list.

Other drugs like cisapride, used for gastrointestinal issues, showed moderate dependence, while medications such as amlodipine (a heart medication) and capromorelin (used as an appetite stimulant) showed weak or negligible interaction with P-gp. Cefovecin (an antibiotic) and ronidazole (used for protozoal infections) were identified as non-substrates, suggesting a safer profile for cats with the mutation.

Why This Discovery Matters

For years, veterinarians have known that certain drugs can cause unexplained adverse reactions in some cats—especially neurological symptoms like tremors, disorientation, or seizures. Now, there’s finally a clear biological explanation for many of those cases.

The WSU test can be used in two main ways:

- Screening new drug candidates before they reach the market.

- Re-evaluating existing drugs that are already being prescribed to cats.

By identifying which medications rely on P-glycoprotein, the veterinary field can avoid giving dangerous drugs to cats with the MDR1 mutation. This could also lead to new safety labels on feline medications—similar to how human medicines list potential drug interactions and genetic sensitivities.

Dr. Mealey emphasized that even cats without the genetic mutation aren’t entirely safe. If two or more drugs that rely on P-glycoprotein are given together, they can compete for clearance, leading to a temporary form of P-gp deficiency. This means drug interactions can mimic the effects of the mutation, causing side effects in otherwise healthy cats.

A Long Line of Discovery

This isn’t the first time Dr. Mealey has made a major contribution to veterinary pharmacology. Back in 2001, she identified a similar MDR1 mutation in dogs—particularly in breeds like collies and Australian shepherds. That discovery revolutionized how veterinarians prescribe medications for those breeds and led to the development of the first MDR1 genetic tests for dogs.

Her new work builds on that legacy. Just like before, she’s not only pinpointed the genetic risk but also created a practical, easy-to-use test that can save animal lives.

The new feline test is already available as a fee-for-service through Washington State University. Pharmaceutical companies and regulatory agencies can also use the published procedure to run their own screenings.

What This Means for Pet Owners

If you have a cat—especially a Maine Coon—it might be worth considering a genetic test for the MDR1 mutation. These tests can often be done using a simple cheek swab by your veterinarian. Knowing your cat’s genetic status can help avoid dangerous medications in the future.

For veterinarians, this discovery adds another layer of safety to prescribing decisions. By consulting P-gp test results, they can choose drugs less likely to cause adverse effects, particularly for cats with complex treatment plans involving multiple medications.

And for drug manufacturers, the test offers a new opportunity to make safer and better-labeled veterinary products. Human medications already include detailed information about metabolism and genetic interactions. It’s only logical that veterinary drugs should follow the same path.

The Broader Science Behind P-Glycoprotein

To understand why this test is so important, it helps to know a bit more about what P-glycoprotein actually does. This transporter protein acts as a molecular pump, sitting in cell membranes and pushing certain molecules back out into circulation or into the bile and intestines for excretion.

In humans and animals alike, it’s one of the body’s most important defense systems against drug toxicity. If P-glycoprotein stops working—either because of a genetic mutation or because two drugs interfere with each other—medications can accumulate where they don’t belong, especially in the brain and central nervous system.

This can lead to severe neurological side effects, such as ataxia, blindness, tremors, and even death in extreme cases. That’s why understanding whether a drug depends on P-gp is crucial for safety, particularly in species like cats that have unique metabolic quirks compared to dogs and humans.

The Future of Safer Feline Medicine

The test from WSU marks a major step forward for feline pharmacology. It’s not just about identifying one dangerous drug—it’s about building a comprehensive safety framework for how we treat cats medically.

The researchers plan to expand their work by testing many more drugs used in veterinary practice. Over time, this could lead to a large, publicly accessible database showing which drugs are safe, risky, or need caution for cats with the MDR1 mutation.

Ultimately, this kind of research could encourage drug manufacturers to include genetic warnings and P-gp dependency data on product labels, giving veterinarians and pet owners clearer guidance.

Research Reference:

Assessment of Clinically Relevant Drugs as Feline P-glycoprotein Substrates – Frontiers in Veterinary Science (2025)