Scientists Confirm the Plague Behind the World’s First Pandemic

For nearly 1,500 years, historians and scientists debated what exactly caused the Plague of Justinian, a devastating outbreak that shook the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire in the 6th century AD. Historical texts described a terrifying disease, but until now there had been no direct biological proof linking it to the plague bacterium Yersinia pestis. That mystery has finally been solved.

A team of researchers from the University of South Florida (USF) and Florida Atlantic University (FAU), working alongside collaborators in India and Australia, have successfully identified genetic traces of Yersinia pestis in human remains from a mass grave in the ancient city of Jerash, Jordan. This marks the first solid genomic evidence that the Plague of Justinian (AD 541–750) was indeed caused by the same pathogen responsible for later outbreaks like the Black Death.

Where the Evidence Was Found

The discovery came from an archaeological site in Jerash, a city that was once part of the Byzantine Empire and a well-known trade hub. Beneath the ruins of a Roman hippodrome, archaeologists uncovered a mass grave dating back to the mid-6th to early 7th century. This timeline coincides with written accounts describing a sudden wave of mortality across the region.

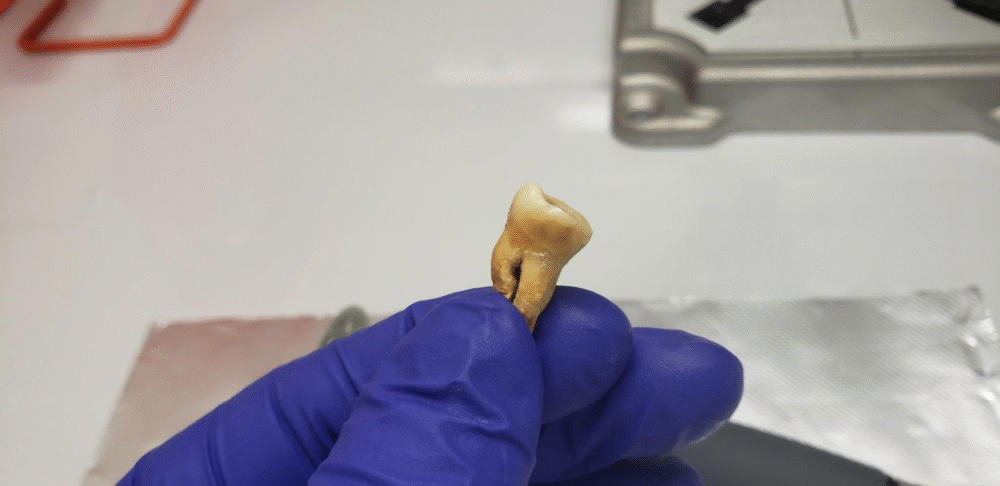

The research team carefully analyzed eight human teeth recovered from the burial site. Using specialized ancient DNA techniques, they extracted and sequenced genetic material. In five out of the eight samples, they identified Yersinia pestis DNA, and the bacterial genomes turned out to be nearly identical.

This level of genetic uniformity indicates a fast-moving, devastating outbreak. Instead of small, isolated infections, the population was struck by a single clonal strain that spread rapidly through the city. The repurposing of a public entertainment venue—the hippodrome—into a cemetery further underscores how urban centers were overwhelmed during the pandemic.

Why This Matters

Although scholars had long suspected that the Plague of Justinian was a plague outbreak, until now the evidence was circumstantial. Previous discoveries of Yersinia pestis DNA were made in Western Europe, far from the epidemic’s supposed epicenter. With Jerash lying just 200 miles from Pelusium in Egypt—the city often described as the plague’s entry point into the empire—this new genetic proof settles the debate.

For centuries, historians had to rely on ancient chroniclers whose descriptions of symptoms were often vague and inconsistent. Without molecular confirmation, some argued the Justinianic Plague might have been caused by another pathogen entirely. These new findings eliminate that doubt.

How the Research Was Done

The study involved advanced ancient DNA recovery methods, which can capture and amplify highly degraded genetic material from centuries-old remains. Alongside the DNA sequencing, the researchers used proteomic analysis to detect proteins consistent with plague infection, and stable isotope analysis to further confirm the archaeological context.

The bacterial genomes obtained from Jerash were compared against hundreds of other ancient and modern Yersinia pestis genomes. This showed that the strain belonged to the First Pandemic lineage, firmly tying it to the time of the Justinianic outbreak.

Broader Evolutionary Insights

The research also revealed that the plague bacterium had been circulating in human populations for millennia before the Justinianic outbreak. The Justinianic strain was not unique in sparking pandemics; later pandemics, including the 14th-century Black Death and subsequent recurrences, did not descend directly from it. Instead, they arose independently from animal reservoirs, showing that plague has emerged in multiple waves across history.

This pattern contrasts with diseases like COVID-19, which originated from a single spillover event and spread primarily through human-to-human transmission. Plague, by contrast, is a zoonotic disease that re-emerges repeatedly when conditions favor its jump from animal hosts—often rodents and fleas—into human populations.

The Historical Impact of the Justinian Plague

The Plague of Justinian erupted in AD 541 and is recorded to have begun in Pelusium, Egypt, before spreading rapidly throughout the Byzantine Empire. Over the course of two centuries, waves of outbreaks persisted until around AD 750.

Contemporary reports suggest that tens of millions of people died, though exact numbers remain debated. The impact was enormous:

- The pandemic weakened the Byzantine Empire, leaving it vulnerable to external threats.

- Economic systems collapsed under the strain of mass death and disruption.

- Entire cities were depopulated, and critical infrastructure faltered.

For historians, this plague represents one of the key turning points in Western history, reshaping the balance of power in the Mediterranean and beyond.

The Archaeological Significance of Jerash

Jerash was one of the most prominent cities in the Eastern Roman Empire, renowned for its architecture and thriving trade. That its hippodrome—originally built for chariot races and public gatherings—was transformed into a cemetery highlights the severity of the crisis.

Such sites offer rare insight into how ancient societies responded to public health disasters. They also show how quickly cultural spaces could be repurposed in times of desperation.

Pandemic Parallels Today

Although the Plague of Justinian belongs to distant history, its lessons remain relevant. The bacterium Yersinia pestis still exists today. Modern outbreaks are rare, but they still happen. In fact:

- In July 2025, a resident of northern Arizona died from pneumonic plague, the most lethal form of the disease.

- Just a week later, a confirmed case appeared in California.

While plague can now be treated with modern antibiotics if detected early, these cases highlight that the threat has never gone away.

The parallels with COVID-19 are also striking. Both pandemics underscore how human connectivity, trade, and urban crowding can accelerate the spread of infectious disease. And just as COVID-19 reshaped global society, the Justinianic Plague permanently altered the trajectory of ancient civilization.

Future Research

The work at Jerash is only the beginning. Researchers are now turning their attention to Venice, Italy, specifically the Lazaretto Vecchio, one of the world’s earliest quarantine islands. This site contains a massive Black Death–era mass grave with more than 1,200 human remains.

Samples from this site are now housed at USF, offering an unprecedented opportunity to study how pathogen evolution intersected with early public health measures like quarantine. By analyzing DNA from these remains, scientists hope to better understand how plague adapted to human hosts across centuries.

Understanding Yersinia pestis

To add more context, let’s look closer at the bacterium itself:

- Pathogen type: Yersinia pestis is a Gram-negative bacterium.

- Transmission: Typically spread through the bite of infected fleas carried by rodents, but can also spread directly through respiratory droplets in the case of pneumonic plague.

- Forms of disease:

- Bubonic plague: Causes swollen lymph nodes (buboes).

- Septicemic plague: Bacteria spread into the bloodstream.

- Pneumonic plague: Infects the lungs and spreads person-to-person; most deadly if untreated.

- Modern presence: Still found in natural reservoirs worldwide, including the American Southwest, parts of Africa, and Asia.

Unlike many diseases that have been eradicated or controlled, plague continues to lurk in the background.

Lessons from History

The confirmation of plague in Jerash is not just an academic achievement. It highlights broader themes:

- Pandemics are recurring features of human history, not isolated events.

- Urban centers and trade hubs have always been particularly vulnerable.

- Despite centuries of progress, zoonotic diseases remain one of the greatest threats to global health.

This discovery reminds us that while medicine and technology have advanced, the fundamental relationship between humans, pathogens, and the environment continues to shape history.

Conclusion

The mystery surrounding the Plague of Justinian has finally been solved. With direct genomic evidence of Yersinia pestis uncovered in Jerash, scientists have provided the missing biological proof of what caused the world’s first documented pandemic. The findings not only confirm historical accounts but also expand our understanding of how pandemics emerge, recur, and continue to challenge humanity.

This breakthrough research is a striking reminder that some pathogens, like plague, never truly disappear—they simply wait for the right conditions to resurface.

Research Paper: Genetic Evidence of Yersinia pestis from the First Pandemic