Thriving Marine Ecosystems Discovered on WWII Munitions in the Baltic Sea

When we think of discarded World War II munitions, our first thoughts are usually about danger, pollution, or underwater hazards. But new research reveals a surprising twist: these submerged weapons are hosting thriving marine ecosystems.

A recent study published in Communications Earth & Environment shows that in the Bay of Lübeck in the Baltic Sea, dumped munitions have become unlikely homes for an abundance of marine life, supporting far more organisms than the surrounding seabed.

A Closer Look at the Lübeck Bay Study

In October 2024, researchers led by Andrey Vedenin used a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) to explore a newly discovered munitions dump site in Lübeck Bay. The investigation involved filming the munitions, taking water samples, and comparing the findings to two areas of nearby sediment.

The team identified the objects as warheads from V-1 flying bombs, which were essentially early cruise missiles deployed by Nazi Germany in the final years of World War II. These were dumped at sea after the war, a common practice before the 1972 London Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution, which prohibited such disposal.

The results were striking: the munitions were teeming with life. On average, the casings supported around 43,000 organisms per square meter, compared to just 8,200 organisms per square meter in the surrounding sediment. That means the dumped warheads had more than five times as much marine life clinging to them.

The organisms included algae, mussels, hydroids, and other species that prefer solid surfaces. What’s remarkable is that despite the toxic chemicals leaking from the munitions, the hard surfaces provided such a valuable structure that they outweighed the risks of exposure.

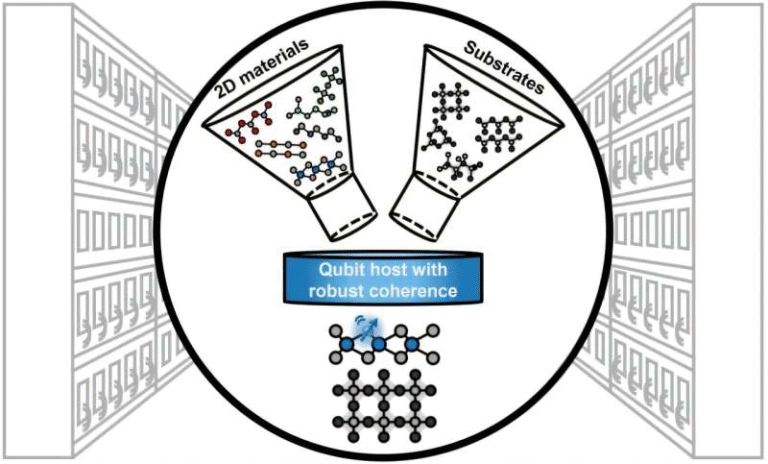

The Role of TNT and RDX in the Environment

The chemical analysis revealed concerning details. Concentrations of TNT (trinitrotoluene) and RDX (Research Department Explosive) in the surrounding water ranged from as little as 30 nanograms per liter to as much as 2.7 milligrams per liter. The higher end of that range is considered potentially lethal for marine organisms.

Yet, the organisms weren’t evenly distributed. Most were found on the metal casings of the warheads rather than on areas where explosive material was directly exposed. The researchers believe this could reflect a natural avoidance behavior, with organisms colonizing areas where chemical exposure was less intense.

The conclusion: although these warheads are unintentionally serving as habitats, they are still sources of chemical pollution. Replacing them with safe artificial surfaces, like concrete reef structures, would offer the same ecological benefits without the toxic side effects.

Why Marine Life Chooses Hard Surfaces

The Baltic Sea is dominated by soft sediment habitats, meaning that hard surfaces for organisms to cling to are relatively scarce. When objects like rocks, shipwrecks, or even discarded munitions appear, they provide a rare opportunity for colonization.

This pattern isn’t unique to Lübeck Bay. Studies around the world have shown similar results:

- Shipwrecks become artificial reefs, attracting fish, corals, and algae.

- Oil rigs often support dense and diverse marine ecosystems.

- Even discarded man-made debris in oceans can become hotspots for marine growth.

In this case, the warheads function much like shipwrecks do, offering a foothold in an otherwise unstable, sandy seabed.

The Dark Side: Toxic Legacy of Sunken Munitions

While the ecological surprise is fascinating, the dangers of old munitions can’t be ignored. Research from the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research in Kiel estimated that between 2017 and 2018, roughly 3,000 kilograms of dissolved munitions-derived chemicals were present in the waters of the southwestern Baltic.

The problem is corrosion. Over decades, the metal casings of these munitions are breaking down, releasing TNT, RDX, and other harmful compounds into the marine environment. Climate change adds another layer of concern: warming seas and stronger storms may accelerate corrosion and leakage.

Monitoring projects have already detected traces of these compounds in sediments, mussels, and even fish. While levels are generally low for now, the long-term accumulation could impact ecosystem health, fisheries, and food safety.

Parallel Case: The Ghost Fleet of Maryland

Interestingly, this isn’t the first time abandoned war relics have been found to support ecosystems. A separate study published in Scientific Data mapped the so-called Ghost Fleet of Mallows Bay in Maryland, USA.

This fleet consists of 147 shipwrecks from World War I that were deliberately burnt and sunk in the late 1920s. Today, they serve as habitats for species such as ospreys and Atlantic sturgeon. High-resolution drone photography revealed just how extensive the ecosystem is, with ship skeletons forming an accidental sanctuary for marine and bird life.

The comparison with Lübeck Bay highlights a broader theme: human conflict has left behind wreckage that nature sometimes reclaims, though often at an ecological cost.

Global Problem of Dumped Munitions

The Baltic Sea is not unique. Across the world, old munitions and chemical weapons were disposed of at sea. For decades, governments dumped unused explosives in oceans, believing the deep water would isolate them. Only later did the environmental consequences become clear.

Key facts:

- Before 1972, sea dumping was a common disposal method for war leftovers.

- The North Sea, Baltic Sea, and Mediterranean are known dumping grounds in Europe.

- In the Pacific, several U.S. disposal sites have been documented.

- Many munitions are uncharted, making them hidden hazards for shipping, fishing, and coastal development.

The issue is now gaining political attention. Germany, for example, has pledged significant funding for munitions clearance, with a €100 million pilot project to safely remove and neutralize dumped explosives.

Robots and the Future of Clearance

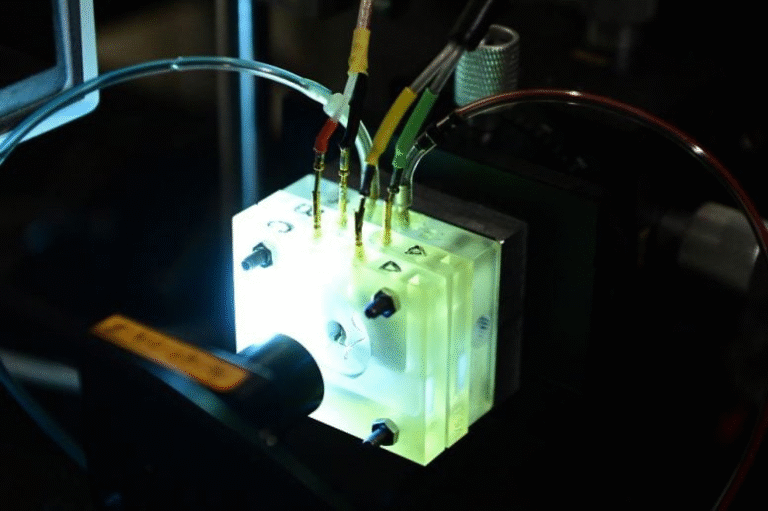

One of the challenges in removing old munitions is safety. Many are unstable, corroded, and highly dangerous to handle. Modern solutions involve robotic technology:

- ROVs and autonomous underwater vehicles can locate and map munition sites.

- Specialized underwater robots can cut, retrieve, or safely neutralize explosives.

- Pilot projects are underway in Europe to test these technologies in the Baltic.

Removing munitions is not just about safety for humans — it’s also about reducing long-term pollution while still offering habitats for marine life through safer artificial substitutes.

Explosive Compounds and Their Effects

To understand the risks, it helps to know more about TNT and RDX:

- TNT (Trinitrotoluene): Commonly used in WWII-era bombs and shells. Toxic to many marine organisms and can disrupt cellular processes. Long-term exposure may impair growth and reproduction in fish and invertebrates.

- RDX (Research Department Explosive): Another powerful explosive, less stable in the environment than TNT but still highly toxic. It has been linked to neurological effects in animals and can persist in sediments.

Both compounds break down slowly in marine environments, and their byproducts can also be harmful. Monitoring studies in the Baltic have detected these substances in mussels and sediments, though usually at levels below immediate danger thresholds. The concern is bioaccumulation — gradual build-up over time through the food web.

Lessons from Nature’s Resilience

The discovery in Lübeck Bay is a reminder of the adaptability of marine life. Organisms can colonize unlikely surfaces and make use of environments shaped by human conflict. Yet this resilience doesn’t erase the risks.

It’s important to recognize the dual reality:

- On one hand, hard surfaces like munitions can provide habitat value.

- On the other, the toxic load they carry threatens marine ecosystems in the long term.

Scientists suggest that removing these munitions and replacing them with safe artificial reefs would strike a balance, preserving habitat while eliminating pollution.

The Bigger Picture

The findings in Lübeck Bay are both hopeful and concerning. They show how life finds a way, even in toxic conditions, but they also highlight a long-lasting problem left behind by human wars. Millions of tons of munitions still lie at the bottom of seas around the world, slowly corroding and releasing chemicals.

Dealing with this legacy will require international cooperation, new technology, and long-term ecological monitoring. In the meantime, studies like this one provide crucial insights into how marine ecosystems adapt — and what risks remain hidden beneath the waves.

Reference: Sea-dumped munitions in the Baltic Sea support high epifauna abundance and diversity