Tiny Ocean Travelers Lock Away Carbon in the Southern Ocean

When you think about fighting climate change, your mind probably jumps to forests, renewable energy, or even electric cars. But here’s something surprising: tiny ocean creatures—barely visible to the naked eye—are quietly helping us out in a big way.

A new study has revealed that these zooplankton, including copepods, krill, and salps, play a massive role in storing carbon in the Southern Ocean. And the way they do it is nothing short of fascinating.

A Hidden Migration Beneath the Waves

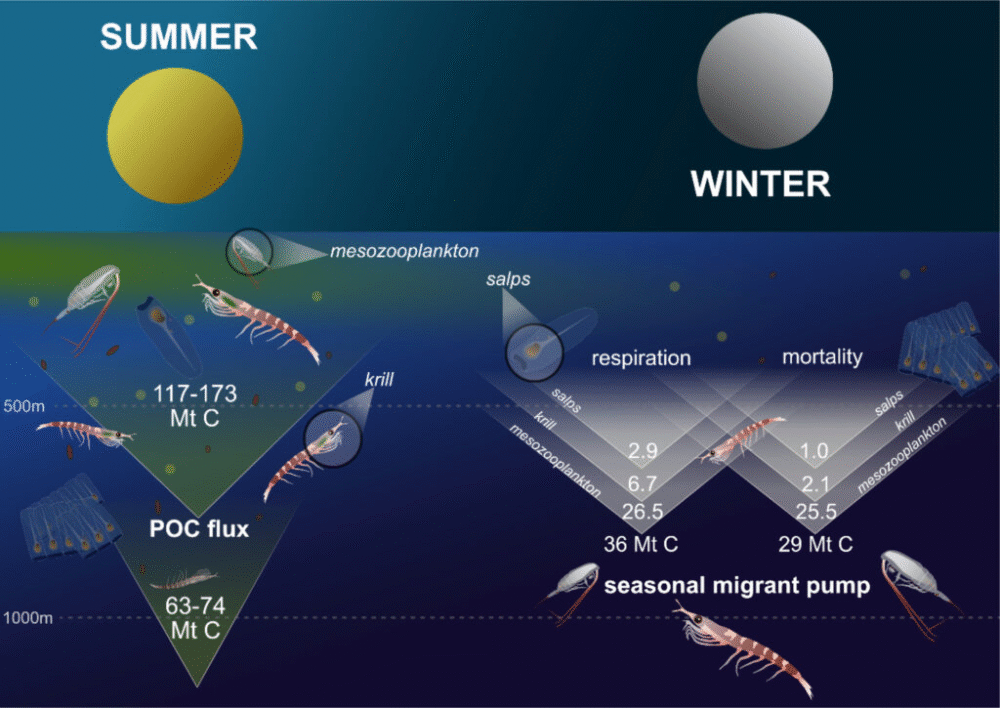

Every autumn, billions of zooplankton begin a journey that most people have never heard of. They migrate from the sunlit surface waters to depths of over 500 meters to survive the winter. While they’re down there, they continue to breathe (releasing carbon dioxide) and many of them die. The result? Around 65 million tonnes of carbon get locked away in the deep ocean every year.

Scientists call this the “seasonal migrant pump.” Until now, climate models didn’t really account for it. Instead, researchers thought most carbon storage in the Southern Ocean happened when zooplankton ate phytoplankton at the surface, and their waste—known as particulate organic carbon (POC)—slowly sank downwards.

That process is important, but this study shows something new: the active migration of zooplankton is a powerful and direct pathway to burying carbon in the deep.

The Numbers That Stopped Scientists in Their Tracks

The research team pulled together data from thousands of net hauls taken over the Southern Ocean—some dating all the way back to the 1920s. By looking at decades of records, they were able to measure just how much carbon these tiny creatures transport each year.

Here’s what they found:

- 65 million tonnes of carbon are stored annually thanks to zooplankton migrations.

- Copepods—small crustaceans often overlooked—do the bulk of the work, accounting for 80% of this carbon transfer.

- Krill contribute about 14%, and salps about 6%.

That’s a staggering amount of carbon quietly tucked away beneath the waves.

Why It Matters

The Southern Ocean is one of the planet’s most important carbon sinks, absorbing about 40% of all human-made CO₂ taken up by oceans. But until now, the role of zooplankton in this process was underestimated.

And here’s the kicker: this method of carbon storage is different from the sinking of waste. While sinking detritus takes carbon down with essential nutrients like iron, migrating zooplankton recycle nutrients near the surface while still sending carbon deep. That makes them especially efficient climate helpers.

Right panel: A new study highlights an additional mechanism, the “seasonal migrant pump.” In autumn, zooplankton migrate to depths below 500 meters to overwinter. During this period, their respiration and mortality directly inject an estimated 65 million tonnes of carbon annually into the deep ocean.

Credit: Yang, G. et al.

As the ocean warms, however, the balance could shift. Krill populations are under pressure from both warming waters and industrial fishing. Copepods may expand into new areas, but that could change how and where carbon gets stored. Understanding these shifts is vital if we want our climate models to keep up with reality.

Voices From the Researchers

Dr. Guang Yang, the study’s lead author, called zooplankton the “unsung heroes of carbon sequestration.” He explained that their migrations represent a massive, previously unquantified carbon flux—one that needs to be factored into climate models.

Professor Angus Atkinson of Plymouth Marine Laboratory added that this study shows the value of big data compilations, which can unlock new insights after decades of careful sampling.

Other co-authors emphasized that protecting these creatures and their habitats is essential. Dr. Katrin Schmidt pointed out that the seasonal migrant pump is a key pathway of natural carbon sequestration in polar regions, while Dr. Jen Freer noted that even though krill often get the spotlight, copepods dominate carbon storage overwinter—a fact with big implications for the future.

Looking Ahead

This discovery doesn’t just change how we think about the Southern Ocean—it could change how we model the planet’s future. Zooplankton migrations might be tiny on an individual scale, but together they create a giant pulse of carbon storage every winter.

As climate change continues to reshape marine ecosystems, keeping an eye on these microscopic travelers may prove more important than ever. After all, sometimes it’s the smallest creatures that make the biggest difference.